![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTORY CONCEPTS

1 What Is Law and Economics?

Law is an ideal subject for economists to study because it provides a wealth of material for evaluating theories of rational behavior. The most creative researcher could not imagine the variety of situations that even a casual examination of legal disputes reveals.

Another reason that economists study law is that both disciplines are concerned, to varying degrees, with incentives. Rational decision makers in economics act to further their self-interest subject to the constraints that they face. Ordinarily, we think of individuals making economic decisions in the context of markets, subject to market prices and incomes, but nonmarket decisions can also be analyzed from an economic perspective. Indeed, the explanatory power of economics is most clearly illustrated in these interdisciplinary contexts.

The economic approach to law assumes that rational individuals view the threat of legal sanctions (monetary damages, fines, prison) as implicit prices for certain kinds of behavior, and that these prices can be set to guide behavior in a socially desirable direction. More than one hundred years ago, the most famous American judge and legal scholar, Oliver Wendell Holmes, set forth a theory of law that well reflects (one might say, anticipates) the economic approach to law described in this book.1 The theory is sometimes referred to as the prediction theory of law.

The key figure in Holmes’s theory is the “bad man,” who we will see has much in common with the rational decision maker of economic theory. The bad man is not bad in the sense that he consciously sets out to break the law; rather, he is a rational calculator who seeks to stretch the limits of law and will break it without remorse if the perceived gain exceeds the cost. Thus, the bad man has a strong interest in knowing what the law is and what the consequences of breaking it are: “If you want to know the law and nothing else, you must look at it as a bad man, who cares only for the material consequences which such knowledge enables him to predict” (Holmes 1897, 459). The economic model of law does not focus on the bad man because economists think people are basically amoral. Many, perhaps most, people obey the law out of a sense of rightness and therefore are not affected by legal rules at the margin. (Such a person will not commit a crime regardless of the chances of being caught or how long or short the prison term might be.) Thus, to examine the incentive effects of law—that is, to examine how it affects behavior at the margin—we must focus on those to whom it is a binding constraint. Nevertheless, we will see that most people respond to the law in this way in at least some circumstances. For example, even people who would not consciously commit a crime regardless of the threat of punishment make decisions while engaging in risky activities (such as driving a car) that potentially subject them to tort liability (or even to criminal fines for speeding).

1.1 Positive and Normative Analysis

Economic analysis of the law comes in two varieties: positive and normative analysis. Positive analysis seeks to explain how people respond to the threat of legal sanctions by posing questions such as the following: Will longer prison sentences deter more crime? How will changes in tort rules affect the accident rate? Or more controversially: Does the death penalty reduce the murder rate? How would restrictions on gun ownership affect the crime rate? Positive analysis thus relies on the assumption that people respond to the law in this manner.

Positive analysis sometimes goes further, however, to assert that legal rules tend to reflect economic reasoning; in other words, efficiency is a social goal that is actually reflected in the law.2 This is not a claim that judges and juries consciously undertake economic calculations to determine the best ruling in individual cases. Rather, it is a conjecture about the overall tendency of judge-made law (referred to as the common law) to reflect economic efficiency as an important social value. This assertion is somewhat controversial, especially among traditional legal theorists who view the law as being mainly concerned with justice (however that is defined). Hopefully, however, the analysis in this book will convince you that the efficiency hypothesis has some validity.

In contrast to positive analysis, normative analysis asks how the law can be improved to better achieve the goal of efficiency. It is like asking how the health care or education system can be made more efficient. This type of analysis relies on the assumption that efficiency is a goal that the law should reflect, and that legal rules should be changed when they fail to achieve it. In some cases this is uncontroversial, as with proposals aimed at improving the efficiency of the litigation process, but the general assertion that efficiency is a social value that the law should promote is not so universally accepted.

The analysis in this book will combine positive and normative analysis. It will focus on positive analysis because that has been the thrust of most recent scholarship in the field. But in cases where the law seems to fall short of efficiency, we will propose better alternatives.

1.2 Is Efficiency a Valid Norm for Evaluating Law?

As noted, critics argue that it is inappropriate to judge laws on the basis of economic efficiency. Instead, they urge that the law should pursue goals like fairness and justice. These are vague terms, but one common meaning has to do with the distribution of wealth in society (distributive justice), and economics surely has something to say about how a just distribution can be achieved with the least sacrifice in resources. Still another meaning of justice may simply be efficiency. In a world of scarcity it is “immoral” to waste resources, and the law should therefore be structured to minimize such waste, at least so that it does not conflict with other goals (Posner 1998a, 30).

Kaplow and Shavell (2002) have argued that social welfare, defined as the aggregation of some index of the well-being of all individuals in society, should be the sole basis for evaluating legal policy. According to this argument, notions of fairness should not influence policy except to the extent that they enhance people’s well-being (which would be true if people have a “taste” for fairness). At the same time, they assert that narrow concepts of efficiency (such as wealth maximization) are also inappropriate because they exclude factors that may affect well-being (for instance, the distribution of wealth).

Nevertheless, they suggest that as a practical matter, efficiency may often be the best proxy for welfare in evaluating specific legal rules. This is especially true of legal questions that are explicitly economic. For example, breach-of-contract remedies should be structured to maximize the gains from trade, and laws governing property disputes should promote bargaining and internalize externalities. However, readers will no doubt object to the use of efficiency alone (or at all) in other contexts (for example, in criminal law), or will see it as too narrow (for example, in medical malpractice cases or environmental accidents). Even the staunchest adherents of the economic approach to law understand this. But it should not deter us from applying economic logic to these contexts to see what insights it might yield, while remaining mindful of competing goals.

2 Efficiency Concepts

The economic approach to law is based on the concept of efficiency. It is therefore important to be specific about exactly what that means. The basic definition of efficiency in economics is Pareto efficiency, but there are other definitions as well.

2.1 Pareto Efficiency

Consider a society consisting of two individuals and a fixed level of goods and services to be distributed between them.3 Define an allocation to be any such distribution. The allocations that we call Pareto efficient (or Pareto optimal) are “best” among all possible allocations in the sense that they satisfy the following two definitions. First, an allocation A is said to be Pareto superior to another allocation B if both individuals are at least as well off under A as compared to B, and at least one is strictly better off. Note that this is a criterion for making pairwise comparisons of different allocations. It merely requires that the two individuals be able to evaluate their welfare (or utility) under any two bundles and decide whether they are better off under A, better off under B, or indifferent between them. Second, an allocation A is said to be Pareto efficient (or Pareto optimal) if there exists no other allocation that is Pareto superior to it.

Note that this definition of Pareto efficiency has the appealing feature that it achieves unanimity in the sense that reallocations are allowed only if neither party is made worse off. In other words, any changes consistent with Pareto superiority should be consensual, meaning that all individuals should agree to them (or at least not seek to block them).4

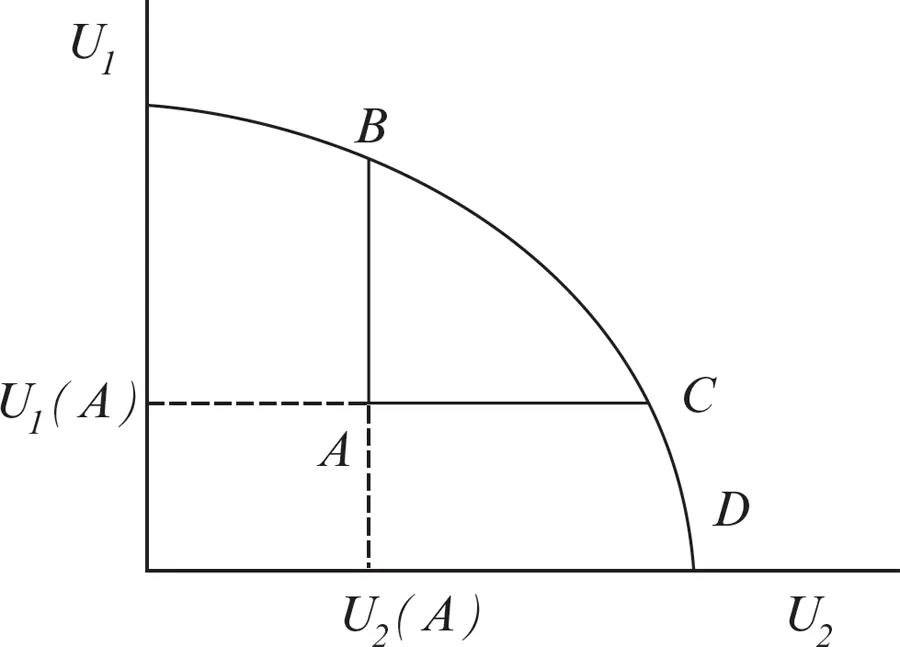

Pareto efficiency does, however, have two rather unappealing features. First, it does not necessarily lead to a unique allocation. In fact, an infinite number of allocations may satisfy the definition, even in our two-person world. This can be seen by looking at Figure 1.1, which graphs the utility possibility frontier for the two individuals in the economy. The utility of an individual is simply an index of his or her satisfaction given any allocation of goods and services. This index allows individuals to make comparisons for the purpose of applying the criterion of Pareto superiority.

Figure 1.1 Utility Possibility Frontier

The negatively sloped curve defines a region that contains all feasible levels of utility for the two individuals, given the fixed level of goods and services available. Points on or inside the frontier represent all feasible allocations. Consider an arbitrary initial allocation inside the frontier, labeled A. Starting at this allocation, we can use the criterion of Pareto superiority to define the area ABC, which contains all of the allocations that are Pareto superior to A. For example, if the utility of person two were fixed at U2(A), then the set of allocations that are Pareto superior to A would be those on the line segment AB since they yield person one at least as much utility as she gets at A while making person two no worse off. The same applies to person two if person one’s utility were fixed at U1(A). Points inside area ABC obviously make both people better off than at A. Thus, point A cannot be Pareto efficient.

The Pareto efficient points in this example are those on the line segment BC since there is no feasible reallocation that can make both people better off. The only possible movement is along the segment, which makes one person better off but the other worse off. Such movements, however, cannot be evaluated according to the Pareto superiority criterion. We therefore say that Pareto efficient points are noncomparable with each other; that is, the criterion of Pareto efficiency has no way of ranking them.

The second unappealing feature of Pareto efficiency can be seen by comparing points A and D. Note that point D is Pareto efficient and point A is not, yet they are also noncomparable: moving from A to D makes person two better off and person one worse off, while movement from D to A has the reverse effect. The reason for this problem is that the definition of Pareto efficiency depends on the initial allocation, or starting point.

These weaknesses of Pareto efficiency, both of which have to do with noncomparability, are significant because most (if not all) interesting questions of legal policy concern changes that help one group of individuals while hurting others. For example, more-restrictive gun laws hurt legal gun owners but may help victims of gun accidents or violence, and more-liberal liability rules for product-related accidents help consumers of dangerous products but hurt manufacturers and their workers. This suggests that Pareto efficiency is not a workable criterion when it comes to evaluating proposed changes to actual legal rules. (In addition, Pareto optimality permits very unequal distributions of income.)

2.2 Potential Pareto Efficiency, or Kaldor-Hicks Efficiency

Economists often address this noncomparability problem by employing a relaxed notion of the Pareto criterion referred to as potential Pareto efficiency, or Kaldor-Hicks efficiency. To describe this concept, notice that movements from B to C (or from A to D) in Figure 1.1 could satisfy the Pareto criterion if person two (the gainer) is made sufficiently better off by the move that he would be able to fully compensate person one (the loser) and ...