Chapter One

Goal Kicking

Heartbreak

There was a funereal air in Adelaide Oval’s media room, as a procession of grim-faced reporters awkwardly deposited their digital recorders between the Channel Seven microphones and Gatorade bottles that were set before Ken Hinkley. When all was in place, the Port Adelaide coach waited impassively as an awkward stillness descended. It seemed nobody wanted to ask the first question. What could you say to a man who had just watched his side’s season ended by an after-the-siren goal in extra time of an elimination final? Eventually, and inevitably, it was the Advertiser scribe and lifelong Port supporter Michelangelo Rucci who broke the silence. ‘Ken, if there was one moment or one thing you could do again, what would that be?’ Rucci asked. A sardonic half smile briefly flickered across Hinkley’s face. ‘Kick straight, probably,’ he deadpanned. ‘That’s been our problem for large parts of the year.’

Hinkley’s pain was amplified by the fact the Power had looked all but home when it surged to a 13-point lead over West Coast early in the first extra period. But the Eagles had refused to go quietly, and stole an improbable victory when the unflappable Luke Shuey drilled a 40-metre set shot from a controversial high-contact free kick in the dying seconds. ‘The Eagles found a way to win and I give them great credit for being able to do that,’ said Hinkley. ‘There were opportunities for both sides, but they kicked straight and we didn’t.’ His summary was simplistic but indisputable. Port had kicked 10 goals 16 to West Coast’s 12 goals 6. It was, in a way, a microcosm of the season. On a basic measure of goals as a proportion of scores, the Eagles had ended the home-and-away season as the league’s fourth most accurate side, while the Power had ranked 13th. Port’s woes were embodied by its leading goal kicker, Charlie Dixon. His performance against the Eagles had been outstanding in every regard bar accuracy. He had booted three goals six, with two of those behinds recorded during the tense final minutes.

As the veteran football writer Ashley Porter cleared his throat, Hinkley braced for the question he knew was coming. ‘What did you think of Charlie Dixon’s game, his performance?’ Hinkley turned his head, raised his eyebrows, and scratched his neck. ‘He’s not overpaid, is he?’ said the coach. But before Porter could reply, Hinkley had swivelled back to address him directly. ‘He’s not overpaid, is he?’ he repeated, a defiant note in his voice. Hinkley rested his chin on his left fist as if pondering his own rhetorical question. Clearly, he had not forgotten the scathing criticism recently levelled at Dixon by Porter’s Fairfax colleague Caroline Wilson, in which she had raised his reported salary of $650,000 to $700,000 per season. ‘No,’ said Porter, slightly taken aback to suddenly find himself answering questions rather than asking them. Hinkley sat up in his chair. He maintained eye contact with Porter, but was now plainly addressing the room. ‘This wonderful place here, they tend to whack people for unknown reasons,’ he said. ‘I couldn’t be prouder of Charlie Dixon, and I, like a lot of people, get sick to death of the stuff that gets thrown around in this game.’

If Hinkley sounded like a protective father, it was because in many ways he was. In his previous role as the Gold Coast Suns’ forward-line coach, he had nurtured Dixon since he was a precocious, if sometimes unruly, teenager. After taking on the Port job, it had been he who had convinced the Queenslander to join him at Alberton, and then defended him throughout an underwhelming first season. And now, at the end of a year in which Dixon had proven his worth, he would not allow him to be blamed for the team’s heartbreaking exit. He had just come from the team’s dressing room, where he had seen the two-metre-tall forward openly sobbing. ‘People sometimes think they don’t care or that it doesn’t mean enough to them, but I wish they could go and watch our players now and understand the hurt they’re going through,’ said Hinkley. ‘We’ve worked really hard at it [goal kicking] all year and we just haven’t been able to quite convert the way we should.’ As the press conference lurched to a close, Rucci made one last attempt to coax a more expansive explanation. ‘Do you become as puzzled as everyone has been for more than a century about goal kicking?’ Hinkley looked down at his clasped hands and let out a world-weary chuckle. ‘We all do,’ he conceded. ‘The amount of work that gets done on it is unbelievable. You’ve just got to factor in that thing called pressure.’

The one thing . . .

Two months earlier, the Western Bulldogs had trudged off the same ground after an even more wretched performance in front of goal. The reigning premiers had conspired to kick a pitiable five goals 15 in a 59-point thrashing at the hands of the Adelaide Crows. ABC Grandstand pundit and four-time premiership coach David Parkin was merciless in his assessment. ‘I’ve been part of this game for 50 or 60 years now, and the one thing that hasn’t got better during that time is the players’ ability to kick the ball between two white posts that don’t move,’ he raged. ‘Every other element of Australian football in my lifetime has gone up by hundreds of per cent, but that’s the one thing we can’t control.’ It was a familiar refrain. In fact, just that week, Cats forward Daniel Menzel had penned an article for his club’s newspaper of record, the Geelong Advertiser, in which he wrote: ‘As our game changes, adapts, improves, and evolves over the years, there is one thing that remains constant and hasn’t progressed – goal kicking.’

When considering these statements from Parkin and Menzel, not to mention the countless others who have argued the same line, it seems reasonable to assume they are referring to the league-wide conversion rate. In analytics, as in arguments, it is important to define your terms, so let us begin by initially describing a team’s or player’s goal-kicking accuracy as the percentage of scoring shots that are registered as goals. Under this definition, the accuracy of the Bulldogs when they kicked 5.15 was 5 / (5 + 15) x 100, or 25%. The team to which they lost, the Crows, kicked 16.8, which made their accuracy 16 / (16 + 8) x 100, or 66%. Accuracy, defined in this way, will always lie between 0% and 100%. It is easy to contemplate ways in which this definition might be improved upon. For example, we could include attempted scoring shots that went out on the full, or exclude rushed behinds. However, these statistics are not available for the entire history of the sport, making any evaluation of long-term trends problematic. Later we will use more advanced data to discover how factors such as shot location can impact accuracy, but for now we will stick with the simplest, most intuitive definition.

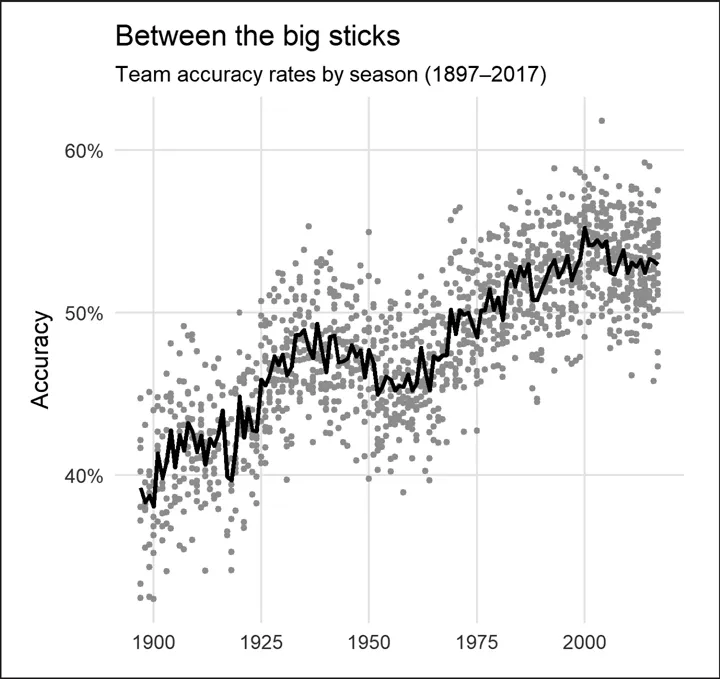

Each of the dots in the chart below represents the season-long accuracy of a single team, while the squiggly line traces the average accuracy of all teams from 1897 to 2017. It is obvious to see that modern teams are, on average, considerably more accurate than those prior to about 1980. There has been a broadly upward trend in accuracy since 1950, with a slight dip during the 21st century. The spread of dots in any given year reveals how variable accuracy was in that season. The 1916 regular season and finals produced the smallest range, spanning just 2.6 percentage points from 42.9% to 45.5%, while 1950 produced the largest range of 15.2 percentage points from 39.8% to 55.0%. It should be noted, however, that there were only four teams in the 1916 competition compared to 12 in 1950. In the VFL’s earliest years, even the best teams converted less than half of their scoring shots into goals. It took until 1920 for a team to end a season with a 50% accuracy level, with Fitzroy achieving the feat after kicking 3.5 in a losing semifinal to finish with a ledger of 185.185. Geelong’s premiership team of 1925 was the first to go above 50%, its 10.19 performance in the Grand Final leaving it with a 248.241 (51%) record for the season.

Since 2000, the difference between the most and least accurate teams in a season has ranged from six percentage points to about double that. The low came in 2009 and the high in 2004, when St Kilda became the only side in the competition’s history to record a season-long conversion rate of more than 60%. Grant Thomas’s side finished the year with 409.253 (62%), including 39.30 during the finals, where it lost to the eventual premier, Port Adelaide. Thomas believed accurate goal kicking to be a football fundamental. He ignored his sports scientists’ warnings against overwork, conducting lengthy goal-kicking sessions both before and after training. One of his favourite drills was called ‘the gauntlet’, which involved players walking through a tunnel of jeering teammates before taking their shots. Thomas was what might be termed a confidence coach, in that he placed the highest value on spirit and morale. To that end, he never monitored or recorded whether his players were missing or scoring at practice. ‘Goal kicking is an outcome, but we wouldn’t talk about the outcome or effects, we’d only talk about the inputs and causes,’ he said. ‘It’s only when you bring the outcome into a skill that you have problems, whether that be with a golf putt, a smash in tennis or a shot at goal, because you’re then thinking about the consequence rather than the cause.’

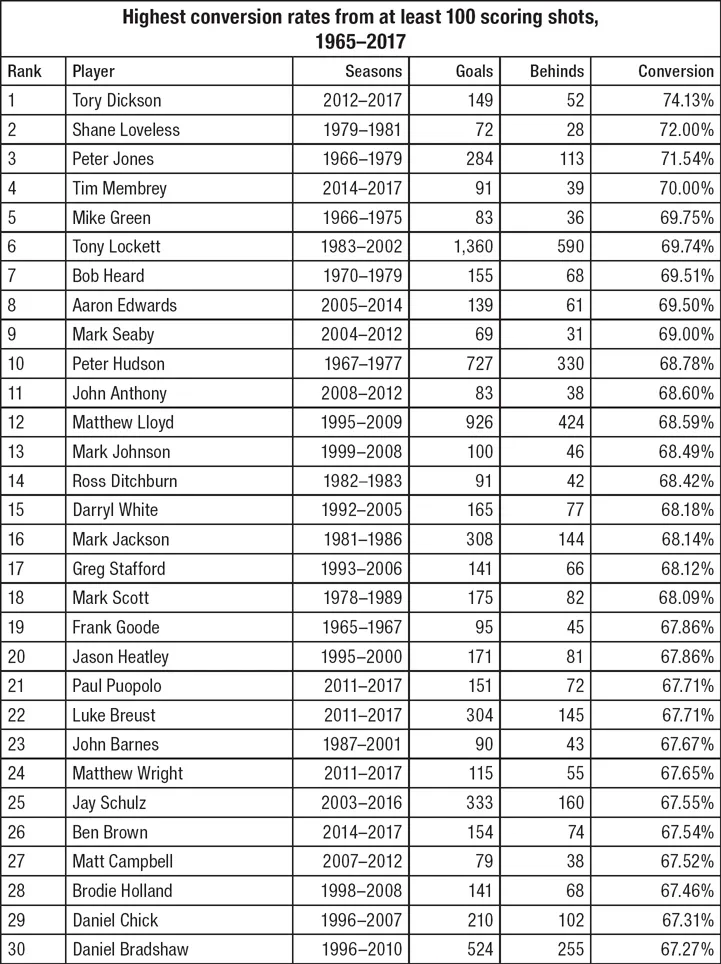

The Saints were also blessed with a supremely talented trio of forwards. The powerful Fraser Gehrig notched a century of goals, finishing with 103.39 (72.5%). The club’s future captain Nick Riewoldt kicked 67.32 (67.7%) and the opportunistic Stephen Milne booted 46.22 (67.6%). Between them, they had contributed well over half the Saints’ majors. In no other season have three players kicked more than half of their side’s goals at a higher conversion rate (69.9%) than Gehrig, Riewoldt, and Milne did in that season. To put their extraordinary accuracy into some context, consider the following table. We have compiled a list of the 30 best career conversion rates since 1965, which is the year from which reliable information about individual behinds scorers is available. To avoid the results being skewed by players with a small sample size, we have omitted those who recorded fewer than 100 scoring shots. Although Gehrig, Riewoldt and Milne failed to make the cut over the course of their whole careers, their 2004 accuracy levels all comfortably fell within the elite bracket. Viewed on its own, Gehrig’s 72.5% would have placed him behind only Western Bulldogs sharpshooter Tory Dickson, who sits well clear on top with a freakish 74.13%.

It is perhaps unsurprising to learn that Dickson had missed the Dogs’ inaccurate performance in Adelaide that had so incensed Parkin. A combination of injury setbacks and patchy form meant Dickson only managed nine games during the 2017 season, during which his team slid from 13th (52%) to last (47%) on our basic measure of accuracy. Still, when he was on the park, he contributed a typically precise 11.3 (79%). ‘It’s something that I take a lot of pride in,’ said Dickson. ‘I always want to finish off my work because as a forward you have limited opportunities, and you want to make the most of the ones you get.’ Dickson’s philosophy has been to keep his goal-kicking process as simple as possible. He follows a three-item checklist: forward momentum, a short ball drop, and a pointed toe on impact. ‘My strength is that even if I miss one of those things, as long as I get the other two right, it will usually still go through.’

Charlie Dixon’s routine, like his surname, is similar but distinct from Dickson’s. Dixon’s key thought when lining up for a set shot is ‘right shoulder, right foot, right post’, a mantra that had been taught to him by Malcolm Blight during his time at the Suns. ‘It doesn’t matter about the wind, I’ll still always aim around there,’ he said. ‘Then it’s basically my right foot in front of my left, a couple of breaths to make sure I’m settled, and then my left foot steps first, a small step into four big steps, into a stride until I feel comfortable, and then I kick the ball.’ At face value, it may seem odd to compare the mechanics of Dickson (the AFL/VFL’s most accurate goal kicker of the past half century) to those of Dixon (the...