chapter one

WE SHOULD TALK POLITICS

We all know the rule. The rule governs church functions, social outings, and family gatherings. The rule is passed down through generations and tended to with particular care by women. The rule is for our own good. The rule prevents fights and conflicts and all appearances of discomfort.

The rule is simple: don’t talk politics or religion.

It’s rude. It’s tacky. It’s unladylike. It will ruin Thanksgiving, ensure your first time teaching Sunday school is your last, quickly end a first date, maybe cost you a promotion. We were both taught at a young age that mentioning anything political is not appropriate in polite conversation, especially for women. The phrase “not to get political” is embedded in our vocabularies and jumps out of our mouths almost reflexively. At family dinners, our grandmothers discouraged any discussion of the latest political scandal or presidential outrage, glossing over uncomfortable moments by ushering everyone toward dessert. Over many years of Sunday suppers, holiday parties, and family reunions, we learned that women shouldn’t make people uncomfortable, especially with their opinions about politics.

It hasn’t always been this way, and it doesn’t have to stay this way. There is a way out of this click-baiting, hyperpolarized, road-to-nowhere cycle. We just have to learn to talk to each other again.

History shows that we have the capacity for problem-solving, even through vigorous disagreement. Our founding fathers and mothers believed in talking politics. Many historians cite the desire to assemble and debate as central to America itself. Hannah Arendt, in On Revolution, argued “that the people went to the town assemblies, as their representatives later were to go to the famous Conventions, neither exclusively because of duty nor, and even less, to serve their own interests but most of all because they enjoyed the discussions, the deliberations, and the making of decisions.”1

They enjoyed it.

Somewhere along the way, we lost our revolutionary passion for talking about the issues that affect our country and our lives. We decided that conversational conflict is impolite at best and dangerous at worst. Unfortunately our attempts to avoid these uncomfortable moments have backfired. In our efforts to protect relationships from political tension, we have instead escalated that tension. Because the reality is that we never stopped talking politics altogether—we stopped talking politics with people who disagree with us. We changed “you shouldn’t talk about politics” to “you should talk only to people who reinforce your worldview.” Instead of giving ourselves the opportunity to be molded and informed and tested by others’ opinions, we allowed our opinions and our hearts to harden.

We sorted ourselves, engaging only with those who were on our side. We also sorted others—based solely on assumptions about their hardened opinions. In the process, we subconsciously and constantly increased the stakes in believing that our personal perspectives are accurate and morally superior.

Today, if and when we do enter a discussion with someone from the other side, we’re ready for battle, not dialogue. The rule that was supposed to prevent others’ discomfort has become a weapon to protect us from our own. Somehow, a concern about others’ feelings has morphed into an obsession with clinging to our talking points, as though those talking points form the very basis of who we are and what we stand for. We don’t want to be challenged or even questioned, because we believe there is too much at stake. We have tied together our religious beliefs, our pride in our upbringings, and our policy positions until they’ve become like a tangled mess of necklaces that we shove in a drawer—still treasured but unwearable. And over time we have lost the ability to sort out why we believe what we believe about our neighbors and perhaps even about ourselves. Approval ratings for politicians in both parties have bottomed out, and our faith in public and private institutions is at an all-time low. It’s no wonder that protests turn violent so regularly that we hardly notice. These were once the spaces—from political parties to pews to protests—where we worked out our disagreements, or at least got comfortable hearing opposing opinions. We’ve stopped practicing good conversations. We’ve disconnected from one another.

If the ramifications of political conversation ended at even the most contentious dinner table, or if these uncomfortable situations were simply a cable television drama that we could turn off, our instincts to confirm our beliefs and avoid any conversations that challenge them wouldn’t be so dangerous. Perhaps we could continue on the path of tuning out the cacophony of political debate. But the reality is that we cannot opt out of the real consequences of politics in our lives. Politics becomes policy, and policy is the road map for the more than five hundred thousand elected officials who make decisions every single day—decisions that determine the roads we drive on, the schools our children attend, the wars we wage, and the taxes we pay. When we struggle at all levels to get anything done—to pass budgets, confirm judicial nominees, and perform even the most basic functions of government, like ensuring our water is safe to drink—it is our daily lives that are affected. This dysfunction isn’t what we want for our children, and it shouldn’t be what we want for ourselves.

Regular people—parents and nonparents, people of faith and atheists, students and teachers, people of all backgrounds and cultures—have to discuss how we want our governments to function and what we want our country to become. We need people who are worried about gas prices and their 401(k)s and studentloan interest rates and laundry and day care to talk about domestic policy. We need people who remember the draft and the uncle who died in Afghanistan and the friend who missioned abroad in Spain to talk about foreign policy. We need parents of children with special needs and gifts talking about education policy. We need people who work help desks across the United States thinking about cybersecurity. We need to show up with the entirety of our life experiences for these conversations.

We need to bring our voices and perspectives to the table calmly, with respect for ourselves and one another, recognizing that we do not live alone. America has never been and will never be homogeneous. We are here to bump up against each other. We need to bring our faith and values not just to specific issues but to the process of engaging in civil discourse. We can share our perspectives on even the most controversial and personal topics. Doing so will de-escalate the rhetoric and open pathways for solutions, innovation, and a stronger national identity.

Others will disagree with us. We have to expect that. Debate is not a dirty word, even if you feel underinformed or ill prepared. It is easy to envision the famous paintings of the Constitutional Convention and think of our founding mothers and fathers as a monolithic group who always agreed. However, anyone who has sung along to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s blockbuster Broadway musical Hamilton knows nothing could be further from the truth. Our patriotic ancestors battled it out over everything from war strategies to presidential pageantry. In fact, let us not forget that they got it plain wrong with the Articles of Confederation before they finally settled on the Constitution we now enshrine as infallible.

They didn’t give up because it was hard, and neither should we. It is nothing short of our patriotic duty to engage with one another as Americans—and not only with those Americans who look like us and act like us and agree with us. We face difficult challenges as a country. We face problems that won’t be solved in our lifetimes. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try. Throwing our hands up in frustration is a natural reaction to a problem as big as America’s current political climate, but that’s only because we feel so disconnected from America’s greatest strength—each other.

Learning to have healthy conflict with each other over political challenges is of utmost importance; in fact, it is a spiritual imperative. We do not demonstrate love toward our neighbors by demonizing them over how they feel about tax policy or reproductive rights. We do not turn the other cheek when we treat politics as an insular sphere in which fighting fire with fire is the only way. We do not live as the hands and feet of a loving creator when we opt out of the processes that dictate roads and bridges, school curriculum and water treatment, war and peace. Neither stridence nor apathy is a virtue. Like it or not, the decisions our government both makes and does not make impact every aspect of our lives. Democratic societies, like churches, are a body. We all affect each other. We can’t sit it out. We can’t move forward if we refuse to ask each other where we want to go.

Talking politics not only has the power to make our communities, states, and country better, but it also has the power to make us better as individuals. Connecting with one another isn’t just the source of American strength. It is also the source of faith, hope, love, and understanding. Our conversations help us to understand on a much deeper level many of the issues that tear America apart. Talking about subjects most people studiously avoid in mixed political company helps us to see where we are right, where we are wrong, and where we have more to learn. More than that, talking with one another helps us to better understand ourselves, to clarify our values and priorities, and to confront weaknesses and attitudes we could have too easily ignored.

And here’s the most surprising thing the two of us have found in talking for a few hours each week about everything from trade policy to the role of the Supreme Court: we enjoy it. Our grannies’ hearts may have been in the right place with all their shushing, but we’d rather channel our inner Abigail Adams than take a second helping of pie. Adams said, “If we mean to have Heroes, Statesmen and Philosophers, we should have learned women,”2 and that’s what we intend to help each other become. Engaging in the issues of our time with people we love, or simply people who love this country as much as we do, is fun. That doesn’t mean it’s easy. It isn’t. But in the immortal words of Jimmy Dugan in A League of Their Own, “It’s supposed to be hard. If it wasn’t hard, everyone would do it. The hard is what makes it great.”3

So let’s do the hard but enjoyable work begun by our founding fathers and mothers. Let’s talk politics.

• • •

In very different ways, the two of us have been talking politics our whole lives.

Sarah learned to talk early and never really stopped, especially as an only child encouraged by the doting adults in her life. When she was young, she thought she had a love of the stage and should pursue acting. Eventually she realized it wasn’t the stage that she loved—it was the microphone. She had plenty of opinions, especially about politics, ready to share. To exactly no one’s surprise she was named Most Talkative in high school. Of course, a young woman with passionate political opinions wasn’t always well received. Sarah spent most of her childhood battling peers (and some adults) who constantly told her to tone it down if she wanted to be liked. Still, with the dream of one day running for office always in the back of her mind, she majored in political science and attended law school in Washington, DC. After graduation she began working in politics, first for Hillary Clinton’s 2007 presidential campaign and then as a legislative aide in the United States Senate.

However, Sarah’s political pursuits took a major detour in 2009 when she convinced her husband, Nicholas, to move to her hometown of Paducah, Kentucky, before the birth of their first son. She rebuilt her life as a stay-at-home mom to (eventually) three boys and as a mommy blogger. By 2015 she had just begun to tiptoe back into the political arena and had recently graduated from Emerge Kentucky, a training program for Democratic women considering public office. Her husband, a passionate podcast listener, kept pestering her to start a podcast.

Sarah had always loved talking politics, but she was no longer a Capitol Hill staffer or even a practicing lawyer. Who would care what she had to say? She was interested in how women worked in the political arena, and she knew that topic would increase in importance with what seemed like the inevitable candidacy of Hillary Clinton in 2016. So Sarah thought she might start interviewing women in politics. She did a few interviews, found them a little boring, and, never one to do something if she was only in it half-heartedly, did nothing with the files for months.

Talking politics by herself was simply too scary.

Enter Beth.

Or reenter. We first met our freshman year of college at Transylvania University. Just as we do now, we had very different approaches to life then, and despite being in the same sorority, our paths were more parallel than intertwined. By 2015 we were close enough to be friends on Facebook—brought together again by our similar journeys toward natural birth (a story for another chapter). Beth had reached out for advice several times, knowing that Sarah had had two successful home births, and they struck up a casual friendship that eventually led to Beth writing guest posts for Sarah’s blog while Beth was on maternity leave.

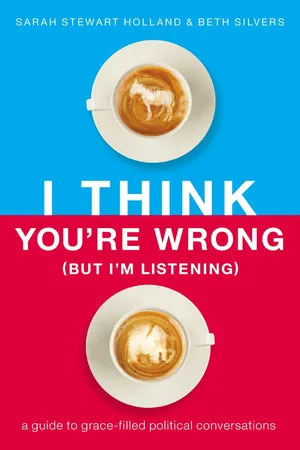

In the summer of 2015, Beth wrote a guest post with a one-word title. That one word would become the clarion call of our podcast and an underlying theme of this book: nuance.

In a reaction to the ever-increasing Facebook vitriol, she suggested a simple hashtag of #nuance to signal the acknowledgment of the complexity behind issues. Complexity that doesn’t always fit in a status update. She wrote: