![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE BEST NEXT STEP

Success is not final; failure is not fatal.

–WINSTON CHURCHILL

You step out the door of a large building and glance at the time. It’s 2:27 p.m. Your next meeting is at three o’clock, and it’s a half hour’s drive away. So you figure you’ve got three minutes to get yourself into your car and on the road. You look in the direction of where you parked—well, where you think you parked—and you start walking.

What happens next is probably the least interesting part of your day. Right on schedule, at about two thirty, you drop into your seat, start the car, and drive off the lot. It’s an unremarkable event, but what it takes to achieve it is actually pretty sophisticated.

At first glance, it may not seem that way. It may seem that all that’s happening is that your brain—your own personal executive office—is setting a goal in the form of an output requirement and a deadline: get to the car in three minutes. Then your feet, which are your workforce, carry out your orders.

Right?

Sort of—but there’s more to it than that. The process does start with a high-level goal set from “above.” But as soon as you start walking, things get complicated. As your feet move across the ground, they must deal with subtle variations in the surface. Is there gravel? Is the ground wet or slippery? Your front line workforce—your foot muscles—compensate without any intervention from management to keep you upright and on track.

Meanwhile, those muscles are dependent on blood oxygen, a resource, to keep going. If they’re getting enough, everything is fine. If they’re not—maybe the pace is too quick or the surface is too difficult—they request more. That’s what we might call an escalation.

The escalation goes first to middle management—your cardiovascular system. In some cases, that system can satisfy the need directly. Your heart pumps a bit harder, and more resources are sent where they’re needed. In other situations, the request is too great. Middle management can’t handle it, so it gets escalated all the way to the top. The request makes it up to your brain, and you get the message: “Breathe harder or walk slower.” And you make a choice.

While the work is going on at the bottom, something else is happening at the top: you’re looking where you’re going. And up in your executive office, you’re processing new information. Maybe you see something in your path—an open hole or a tree—and decide to go around it. Or maybe you notice that you’re walking toward the wrong car and you need to change direction.

So along you go. You have information flowing up from the bottom of your metaphorical organization and information flowing down from the top. You have decisions being made at all levels, with escalations when necessary. And you have a whole system—that’s a key word, system—processing all of the information and decisions for one reason: so that in this moment you take the most reasonable step toward your goal, and then in the next moment you take the next most reasonable step from there.

Let me repeat that: you take the next most reasonable step from there. Not the next most reasonable step as you foresee it from here.

In other words, you Iterate.

Really, you have no choice. The total trip to your car may be a few hundred steps, but you can’t foresee more than the first five or ten when you start. You can’t possibly chart your course completely before you begin. And yet, if every step you take, from the first to the last, isn’t the most reasonable and useful one at that moment, you’ll waste time and energy. After each step is complete, the information that came from it—new information that wasn’t available before you took it—must be incorporated into the decision about the next one.

Iteration is the way effective systems solve problems whose solutions are too complex to be predefined. It’s how trees take shape as they grow. It’s how computers simulate weather, traffic patterns, and aircraft flight. It’s how humankind got from the first Wright Flyer to the mass-produced Boeing 747. And it’s how you walk to your car.

If you’re still not impressed by your trip across the parking lot, let’s talk about what doesn’t happen along the way.

You don’t find yourself paralyzed on the sidewalk with your feet awaiting permission from your brain to take the next step because you stepped on a piece of gravel that wasn’t in the original plan. You don’t stop in the middle of the street for a process debate about left-foot-first versus right-foot-first. You don’t see an open manhole coming forty paces away, repeatedly decide to change direction, and then fall down the hole anyway. You don’t arrive at the wrong car or arrive 50% to 200% later than you expected (as many business initiatives do). You don’t run out of blood oxygen because your foot muscles can’t get what they need from your cardiovascular system. And you don’t roam the parking lot in circles, trying to decide whether you’ll ever get to the car or whether you should cancel your three o’clock meeting.

Any of those outcomes would be, well, dumb. But they don’t happen. Not on your walk to the car.

They do happen in organizations. Micromanagement from above stalls progress below. Turf wars stifle output. Lack of flexibility makes even the most foreseeable problems impossible to avoid. Plans and budgets never catch up with real complexity and cost. Resources are held hostage by cumbersome approval processes. And lack of information from above and below pollutes decision-making at all levels.

You’ve probably been part of a “dumb” work group or organization—one that delivered less intelligent decisions and results than those its individual members could have come up with alone. If so, you know how frustrating and wasteful this is.

If you’re lucky, you’ve also been part of a smart organization—one that Iterates. One that moves the right information up and down the hierarchy, in regular and useful ways, in support of good decisions. One that makes good decisions at every level. One that doesn’t get stuck in an overly rigid plan but instead stays flexible as it pursues clearly defined outcomes. One that continually asks itself the question, “What’s the next most logical step to be taken?” and then takes it, learns from it, and repeats.

If you’ve had this experience, you know how engaging and exciting it can be to Iterate—to work in groups that produce a whole lot more intelligence together than their members could alone. If you haven’t had it, you should know that such places exist. They do, and they’re not nearly the minority that you may imagine. Simply look for the highest-performing entrants in any given market space. Chances are they’re Iterating.

Whether or not you’ve experienced such an organization firsthand, you need to know not only that they exist but also that they’re consistent and recognizable: they share common behaviors that can be defined, observed, encouraged, and rewarded. In my firm’s work with our clients, we rely on more than seventy years of research, information, and experience to define exactly what people do in these organizations—especially the people in management. And we have almost that much collective experience helping leaders, managers, and their teams to improve at it. Anyone who runs or advises a management team without understanding Iteration is doing both the team and the company a huge disservice.

This book is your guide to running an Iterative organization. It’s written with three goals in mind. First, for you to understand: to learn the key behaviors of management that make an organization Iterate (and keep it from being dumb). Second, for you to assess: to recognize the extent to which those behaviors are present or absent—in yourself as a manager, among the managers you supervise, and in the managers around and above you. And third, for you to improve: to help yourself, your team, and your organization to Iterate—even just a little more than they do now.

Your copy of this book includes prepaid access to a library of videos, including Iterate—The Walk to Your Car. You can watch the video now, then return to it later to refresh your memory or share concepts with others. Create your free account and watch any video, anytime, at IterateNow.com.

Reflect on the extent to which your organization as a whole exhibits Iterative characteristics.

1.How does your organization allow you to repeatedly “take the next most logical step,” as in the story of your walk to the car? How does it get in your way?

2.How do you allow the organization you manage to “take the next most logical step”? How do you get in its way?

Iteration Requires Feedback

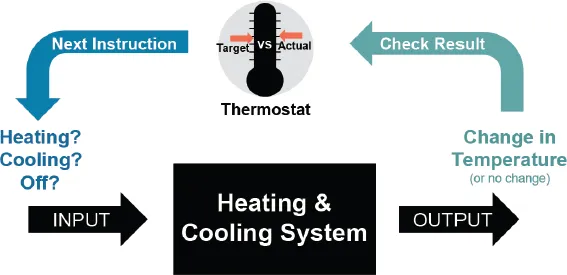

The idea of Iteration applies to many natural and man-made systems. A pretty simple one involves the temperature in our homes.

You walk over to the wall and set your thermostat to the temperature you want. Then the air conditioner or heater turns on and off all day long to keep your house at about that temperature.

Now, you might do a lot of thinking about what temperature to set, and if you live with other people, there might be some serious debate about that! But once the number is set, unless something goes wrong, you can pretty much trust that the temperature will stay consistent. A lot of things change throughout the day—the outside temperature, hot sun coming through the windows, cold rain falling on the roof, the number of people inside, and whether anyone is using the stove, to name a few—and yet, the system still gets it right.

It gets it right through Iteration. Think about it: the heating and cooling equipment is an output machine. To act, it needs a simple input—an instruction to turn the heating on, the cooling on, or the system off. With that, it does its work, and it produces output—a change in the temperature or no change, depending on the input.

The thermostat gives input to the machinery—not just any input but input intended to drive future output in the right direction. It reads the temperature in the house, compares it to the target you set, and determines the next most reasonable step. If the house is warmer than the set point, it switches on the cooling. If the house is colder, it switches on the heating. If the temperature is about right, it switches everything off. And then it checks again.1

The thermostat provides feedback so that the heating and cooling system can Iterate.

The thermostat, in other words, provides the system with feedback. Without it, you’d constantly be too hot or too cold. With it, regular adjustments based on th...