![]()

CHAPTER ONE: POPULAR NARRATIVES

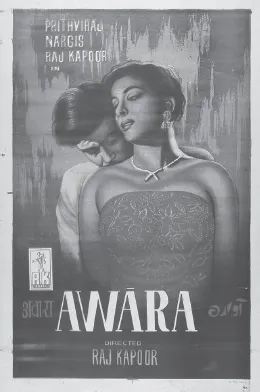

AWAARA (THE VAGABOND, 1951, DIR. RAJ KAPOOR)

Produced by Raj Kapoor for R. K. Films Ltd & All India Film Corporation

Written by K. A. Abbas (screenplay & dialogue), Story by V. P. Sathe & K. A. Abbas

Cinematography by Radhu Karmakar

Film Editing by G. G. Mayekar

Art Direction by M. R. Achrekar

Set Decoration by K. Damodar

Choreography by Krishna Kumar, Surya Kumar & Madame Simkir (dream sequence)

Sound Editing by Allaudin Khan Qureshi

Original Music by Shanker-Jaikishan

Lyrics by Shailendra & Hasrat Jaipuri

Playback Singers – Manna Dey, Lata Mangeshkar, Mukesh & Mohammad Rafi

Runtime: 193 min

Main Cast:

| Raj Kapoor | Raj |

| Nargis | Rita |

| Prithviraj Kapoor | Judge Raghunath |

| K. N. Singh | Jagga |

| Shashi Kapoor | Young Raj |

| Leela Chitnis | Leela Raghunath |

| B. M. Vyas | Dubey |

SYNOPSIS

Judge Raghunath (Privithraj Kapor) and Leela (Leela Chitnis) are happily married. A local bandit Jagga (K. N. Singh) kidnaps Leela in revenge for being sent to jail by Judge Raghunath. While Leela is in captivity Jagga discovers that she is pregnant. However, Raghunath is not privy to such information. Upon Leela’s return, Raghunath is delighted to hear the news of the pregnancy but secretly begins to suspect the child might not be his. Overcome with paranoia, Raghunath ejects a pregnant Leela from the house. Ostracised and impoverished, Leela struggles to put her son through school. When Leela falls ill, Raj feels helpless until Jagga intervenes to take Raj under his wing. Jagga knows Raj is Raghunath’s son and sets about to teach the Judge a lesson. Raj is caught stealing bread and sent to jail. Upon his release Raj the petty criminal is now grown up and leaves prison with an aim to reform. He meets Rita, and they quickly discover they were once childhood friends. A romance develops between Raj and Rita. We discover that Rita lives with Judge Raghunath and looks after him. To win Rita’s respect, Raj attempts to reject the life of crime and get a normal job but he finds it difficult with people like Raghunath judging him. In defending the honour of his mother Raj kills Jagga. On her deathbed Leela finally reveals to Raj that his father is Judge Raghunath. A furious Raj tries to murder Raghunath but fails and is put on trial. In court Rita defends Raj and Raghunath finally accepts the legitimacy of his son. Although Raj rejects his father’s premature reconciliation, Rita promises to wait for Raj once he is released from prison.

1. RAJ KAPOOR IN THE 21ST CENTURY

The Kapoor family is unique in the history of cinema, Indian or international. In the first decade of the new millennium, the fourth generation of Kapoors continues to be on the cinema marquees. (Jain, 2005: 14)

In late 2007 Saawariya (Beloved),1 the first Indian film to be fully financed by a Hollywood studio (Sony Pictures), opened in cinemas opposite the Shahrukh Khan vehicle Om Shanti Om. Accusations of nepotism predictably greeted the release of Saawariya as it featured in the lead roles two newcomers from illustrious cinematic dynasties: Ranbir Kapoor2 (son of Rishi Kapoor) and Sonam Kapoor3 (daughter of Anil Kapoor). Based on a short story by Dostoevsky (‘White Nights’) and orchestrated by director Sanjay Leela Bhansali, Saawariya, like a lot of Indian cinema today, owes an oversized debt to the legacy of the Kapoor dynasty. Bhansali’s homage is an affectionate one, visualising the larger than life persona of Ranbir Kapoor’s Raj around a litany of intertextual references recalling most memorably the films of his grandfather Raj Kapoor. The on-screen persona of the lovable vagabond whom Raj Kapoor immortalised in such classic films as Awaara (1951) and Shree 420 (Mr. 420, 1955)4 finds a personal connection in the opening of Saawariya which sees a youthful Raj arriving in the city as the innocent stranger.

A great deal has been written of the much-publicised relationship between Raj Kapoor and his muse, Nargis. Best remembered for her role in Mehboob Khan’s Mother India (1957)5, Nargis starred in a total of sixteen films with Raj Kapoor. Raised in a middle class Muslim family, Nargis, like Raj Kapoor, was a child star, appearing in her first film at the age of six. Before she came to work exclusively for Raj Kapoor, beginning with Aag (Fire) in 1948, Nargis was already a star in her own right having acted in a number of mainstream films. Nargis maintained a low public profile and was one of the first Indian film stars to use her fame to propagate the cause of charitable organisations. She exuded a combination of traditional feminine qualities alongside a secular, progressive vision of Indian society that director Mehboob Khan exalted in Mother India.

On its release, Awaara achieved widespread critical and commercial acclaim, breaking through into the international markets and demonstrating just why Raj Kapoor had endeavoured to create his own film studio and production banner. Awaara became hugely popular in Russia, and Raj Kapoor’s persona of the lovable vagabond struck a chord with audiences who revelled in the film’s sympathetic depiction of an individual consumed and destroyed by the capitalist city. The Marxist tendencies of influential scriptwriter K. A. Abbas might have had something to do with the warm ideological embrace that greeted the film when it opened in the Soviet Union. Elevated to the status of superstars, both Raj Kapoor and Nargis enjoyed a euphoric reception when they visited Russia in 1956. In Madhu Jain’s fascinating book on the Kapoor dynasty, she states that it was the trip to Russia which finally made Nargis realise that it was her director Raj Kapoor who was the real star in their relationship. It was the beginning of the end to their much publicised director-actress collaboration. A year later Mother India reinvented Nargis, transforming her into one of the most powerful stars in the industry. The famous Raj Kapoor-Nargis love affair was finally brought to a close when Nargis surprised those around her by marrying actor Sunil Dutt.6 Her last appearance for Raj Kapoor would amount to a fleeting cameo in the 1956 film Jagte Raho (Stay Alert).

In Saawariya, actor/director Raj Kapoor’s cinematic muse Nargis finds authorial expression in the character of Sakina, played by Sonam Kapoor. The continuing attraction of Raj Kapoor’s films underlines the dominant hold he exacts over contemporary Indian cinema. In a key scene towards the end of Saawariya, Raj and Sakina flirt with one another around a fountain while it begins to snow. As Raj catches Sakina before she tumbles from the fountain, he gazes romantically into her eyes. As he does so the iconic bowler hat and umbrella framed against the glow given out by the neon sign from the RK bar references both Shree 420 and most strikingly the famous RK logo that was taken from the embrace between Raj Kapoor and Nargis in Barsaat (Rain, 1949). In this celebratory pause, the past and present generations of the Kapoor dynasty interconnect. It is one of the most beautifully judged moments in the entire Bhansali venture, and its entire emotional resonance could only be generated by a director in awe of their cinema idol; Raj Kapoor.

Figure 1. Saawariya (2007) - Raj and Sakina’s magical encounter.

2. RAJ KAPOOR – A FAMILY AFFAIR

Before Raj Kapoor, there was Prithviraj. Born in Lyllapur (now Faisalabad, Pakistan), Prithviraj Kapoor came from a middle class background, having been educated at Lahore University where for a brief spell he studied law. However, Prithviraj soon abandoned his studies, making the arduous journey to Bombay in the late 1920s. Prithviraj’s rag to riches transformation from penniless actor to one of the first Indian film stars of the silent era has become part of popular cinematic folklore. He was quick to carve out a niche in the immensely popular historical epic genre. Prithviraj had many significant star qualities including a physical prowess, good looks and a powerful voice. However, it wasn’t only cinema that motivated Prithviraj; theatre was also a passion.

In 1944 Prithviraj finally formed his own theatre company, Prithvi Theatre, and toured across India for 16 years with a range of widely acclaimed Hindi plays. The company was supported financially through Prithviraj Kapoor’s career as a film actor in the Indian film industry. Many of the plays explored social and political issues of the time. Ghaddar (1948) and Ahooti (1949), for instance, dealt with partition. In 1960, due to ill health, Prithviraj Kapoor was forced to disband the company, which had run successfully for 16 years. His son Shashi Kapoor, together with Jennifer Kendal, revived the spirit of the company when they set up a memorial trust in the 1970s. In 1978, Prithvi Theatre was constructed in Juhu, Mumbai. Sanjna Kapoor, granddaughter of Prithviraj, currently runs the theatre as a non-profit organisation.

The socialist ideals that ran through the thematic core of his company came from his own political affiliations with the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which at the time was arguing for Muslim and Hindu unity in the face of looming partition. In 1931, Indian cinema’s first sound feature, Alam Ara (The Light of the World), directed by Ardeshir Irani, featured a fresh-faced Prithviraj in a starring role, cementing his successful transition from the silent to the sound era. Freely alternating between theatre and cinema underlined his exceptional versatility as an artist. In 1941, Prithviraj’s role as Alexander the Great in the 1941 film Sikandar was further proof that he had achieved commercial and critical success on his own terms. Prithviraj unselfishly channelled most of his salary into the theatre company.

The close relationship between theatre and cinema was to have a decisive influence on the visual style Raj Kapoor developed in the early phase of his career as a film-maker. The repertoire of notable writers, performers and technicians that worked for the Prithvi Theatre Company shared many of the same socialist ideals. However, the committed and engaged political doctrine adhered to by Prithviraj and his regular collaborators was not wholly shared by Raj Kapoor, who preferred popular entertainment to ideological fervour. The shadow cast by his father was considerable and perhaps the decision to pursue filmmaking and ultimately to sideline theatre was motivated by a desire to excel in an area of cinema that had yet to be broached by the multi-talented Kapoor family.

The beginning of Raj Kapoor’s career was marked by his directorial debut in 1948 with Aag. Not only was Aag one of the first post-partition films, it was also radically distinct in the contextual dimensions that would shape the ideological content of the films Raj Kapoor directed in the 1950s. Nineteen forty-seven was a watershed year in the history of India, signalling the birth of a new modern India under the secular leadership of Jawaharlal Nehru7 while marking the partition of India and the subsequent formation of Pakistan as a Muslim nation. Prior to partition, communalism8 had become a real social problem and the ugly skirmishes between Muslim and Hindu communities in Calcutta during 1946 prefigured much of the trauma of ancestral separation and mass exodus that would be witnessed during partition.

The aftermath of World War II meant neo-realist film-makers in Italy had to respond to the moral and spiritual crisis facing European society. Indian film-maker and IPTA member Chetan Anand shared the call for a new realist doctrine based on leftist politics. Neecha Nagar (Lowly City, 1946), inspired by Maxim Gorky’s Lower Depths, resulted in the film sharing the coveted Grand Prix at the 1946 Cannes Film Festival with Rossellini’s Roma, città aperta (Rome, Open City). Released in the same year as the official IPTA production Dharti Ke Lal (Children of the Earth), Neecha Nagar established an important thematic precedence tied to the work of Raj Kapoor and his scriptwriter Khwaja Ahmad Abbas. In Neecha Nagar we are presented with a village, signifying utopian socialist ideals, struggling to counter the corrupting weight of modernity. This epic rural vs. urban conflict would become a defining ideological characteristic of the Hindi realist melodrama. Simultaneously, the expressionist imagery found in Neecha Nagar would inevitably have an impact on Raj Kapoor’s visual approach to Awaara. On a final note, Chetan Anand’s film hinted at the possibility of an emerging social realist vein tied inextricably to the political framework of the IPTA.

Key to the Marxist leanings of the IPTA was Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, whom Raj Kapoor had lured away from his father’s theatre troupe. As a prolific scriptwriter and director K. A. Abbas would go on to work on many of Raj Kapoor’s most accomplished and ideologically sophisticated films including Awaara and Shree 420. The contribution by K.

A. Abbas to the formation of Indian cinema as a classical art form during the 1940s and 1950s has been somewhat overlooked. Released in the same year as Neecha Nagar, the directorial debut of K. A. Abbas Dharti Ke Lal documents the Bengal famine of 1943 and demonstrated that cinema could be used as a tool for political re-education.9 The IPTA as a creative source of political ideals needs further study if we are to understand the relationship between theatre and cinema at a time when the film industry was going through a transitional period. At the time, Bombay Talkies was one of the most successful film studios.10 Raj Kapoor’s spell at the studio taught him that artistic freedom could only be pursued if you had independence.

In 1948 he established RK films, aspiring to emulate an auteur like Chaplin. Though Aag was the first film to be made under the newly formed RK banner, Awaara was far more important. Not only was the film a commercial success, it was the first film to be shot at the newly built RK studios in Chembur, Bombay. The presence of his father, Prithviraj Kapoor, in a central role, of his youngest brother, Shashi Kapoor, as the young Raj, and of Nargis as the love interest underlined the personal nature of the production. In addition, a memorable screenplay by K. A. Abbas and musical compositions by the legendary pairing of Shankar-Jaikishan added to the euphoria that surrounded the release of Awaara. Awaara seemed to act as a creative high point in the first phase of Raj Kapoor’s career as a director, which began in 1948 with Aag. It is hard to believe that he only directed ten feature films in a career that was cut short at the age of 63.

What set Raj Kapoor apart from his contemporaries, including Bimal Roy, Mehboob Khan and Chetan Anand, were his multi-faceted abilities. His output as an actor and producer must also be considered seriously alongside the films he directed. In many ways, his role as a producer was equally indicative of his imposing creativity. Boot Polish (1954) and Jagte Raho may have been helmed by different directors but they bore the unmistakable authorial signature of Raj Kapoor. In such a context he was more than just the showman; he was a great film-maker and one of the first mainstream Indian auteurs.

3. IDEOLOGY OF THE OPPRESSED

Many Indian films produced in the 1940s drew their inspiration directly from Hindu mythology. The story for Awaara built on ‘the unresolved guilt of the epic hero Ram in sending Sita to a life-long exile because of a baseless charge against her virtue and fidelity; it narrated the injustice done by a man who casts aside a virtuous woman on grounds of suspicion and a motivated allegation’ (Bakshi, 1998: 103). In the film, the modern-day Sita has a son who grows up to challenge the injustice committed by his father only to be victimised further by society.

K. A. Abbas was keener than his friend Raj Kapoor to use the sentimental depiction of the common man to uncover and examine the state of society through popular cinema. It was Raj Kapoor’s role to translate such ideological sentiments into a melodramatic narrative form that employed expressionism as a dominant visual style. The opening to Awaara begins with the sta...