![]()

1

WHAT IS LYME DISEASE?

BASIC FACTS

Lyme disease (also known as Lyme borreliosis) is the most commonly reported vector-borne illness in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that more than 330,000 individuals are diagnosed with Lyme disease each year in the United States alone. Although the illness was named after a town in Connecticut, Lyme disease is not confined to the United States. In fact, more than eighty countries have reported cases, and the earliest reports come from Europe, not the United States.

The causative pathogen, Borellia burgdorferi, is a spirochete or spiral-shaped bacterium that infects humans through the bite of the black-legged tick—sometimes referred to as a “deer tick.” During the initial blood meal by the tick, the B. burgdorferi bacteria are injected into the skin. Among most patients, this then triggers an inflammatory response that manifests as an expanding red rash known as erythema migrans. This is the most common presenting sign of the disease and usually develops within two to thirty days after infection. It is typically a round or oval, solid red rash that grows in size over time; sometimes it resembles a bull’s eye with a red perimeter and a paler central clearing. However, some patients never develop symptoms; the immune system clears the infection on its own and these individuals have no knowledge of having been infected with B. burgdorferi. Others don’t see the rash or have only mild symptoms, so they don’t seek medical attention; these patients may develop more serious manifestations weeks or a month later.

As the B. burgdorferi spirochete spreads locally within the skin tissue, it may enter the bloodstream—usually for just a brief period of time. Once in the bloodstream, it gets distributed widely throughout the body. The spirochete seeds whichever organ or tissue it has reached (e.g., collagen tissue, joints, muscles, brain, peripheral nerves, heart), often causing inflammation in that tissue. The initial and ongoing immune response to this invading organism can lead to a wide range of symptoms, the most common being fever, joint pain or swelling, muscle pain, marked fatigue, headaches, stiff neck, nerve pain, irritability, cognitive problems, and, less often, cranial nerve palsy, meningitis, or cardiac inflammation or conduction block. The initial symptoms may be mild and may go noticed by the patient, or they may be quite severe, leading to emergency medical care. Among patients for whom the infection is initially unnoticed and untreated, the infection may resolve or remain quiescent for many months or even years, only later manifesting as an arthritic or neurologic illness.

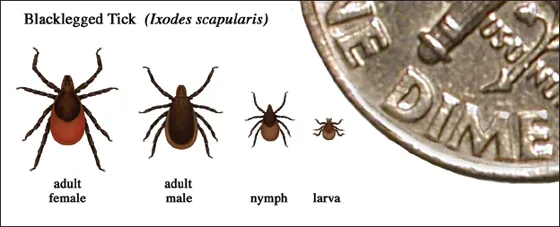

FIGURE 1.1

Relative sizes of black-legged ticks at different life stages. Adult ticks are the size of a sesame seed and nymphal ticks are the size of a poppy seed.

Courtesy of the CDC.

Because of its initial presentation as a skin rash, its potential to involve many different organ systems, and its spirochetal etiology, Lyme disease has been compared to another disease caused by a spirochete, syphilis, which causes complex and chronic symptoms and in the twentieth century was called the “Great Imitator.” Renowned physician Dr. William Osler said in the early twentieth century, “He who knows syphilis knows medicine,” and today the same holds true for Lyme disease.

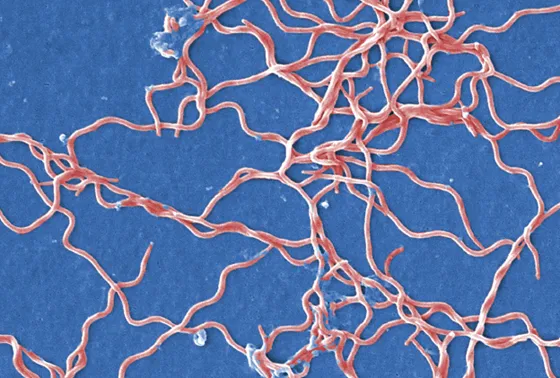

FIGURE 1.2

This digitally colorized scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image depicts a grouping of numerous Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria derived from a pure culture.

Courtesy of the CDC/Claudia Molins.

Because symptoms and signs of Lyme disease can be diverse and blood tests (as with other diseases) are not 100 percent reliable, diagnosis is based on a clinical history obtained from the patient and a thorough physical exam, supplemented by blood test results. This approach to testing is typical of the process physicians follow to make most diagnoses. First, the clinical presentation and risk factors are assessed and then the test is ordered. If the characteristic expanding rash is present, blood tests are not typically ordered, as at this early stage antibody-based tests are unlikely to be positive. Blood tests are not required to make a diagnosis of early Lyme disease when a patient presents with a characteristic rash after having been exposed to a Lyme endemic area. Clinicians who see this rash and know that the individual has been to a Lyme endemic area recently should immediately prescribe antibiotic treatment for presumed Lyme disease. Unfortunately, not all clinicians are aware that treatment should be started right away. Although initial blood tests for Lyme disease at the time of the rash are often negative (50 to 65 percent of the time), blood tests drawn several weeks later are more likely to be positive; at this later point, the blood tests have much better (but not perfect) sensitivity because the antibody response has had time to develop.

Many knowledgeable clinicians know to ask patients with suspected Lyme disease essential questions about tick bites, duration of tick attachment, expanding rashes, flu-like symptoms in the spring and summer, residence in or travel to Lyme endemic areas, and history of other tick-borne infections in themselves, close family members, or neighbors. Activities like golfing, gardening, hiking in the woods, and walking through leaves or tall grasses increase the likelihood of tick exposure. Forest workers and hunters are at high risk. In the United States, certain regions, including the Northeast, Mid-Atlantic States, upper Midwest, and Pacific coastal states, have a particularly heavy burden of Borrelia-infected ticks that lead to Lyme disease. Lyme disease, however, continues to spread geographically. The ticks that transmit the infection have now been identified in nearly 50 percent of the counties in the United States, spread across forty-three states (Eisen, Eisen, and Beard 2016). Because the geographic range of the disease is expanding and because people who don’t reside in Lyme endemic areas may well vacation in areas where it is prevalent, all health care clinicians need to be aware of Lyme disease.

Outside of the United States, Lyme disease is generally referred to as borreliosis because it is recognized as being caused by multiple spirochetes of the B. burgdorferi genospecies complex. Lyme disease is the most commonly reported tick-borne infection in North America and Europe. Worldwide, Lyme disease has a particularly big impact on Europe and Asia. Its incidence is low in the United Kingdom, Japan, and Turkey, while it is quite high in Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Lithuania, Slovenia, and Estonia. In the northern and eastern regions of Europe (e.g., Croatia, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Scandinavia, Czech Republic, Baltic states), the ticks are most likely to carry Borrelia afzellii, which causes primarily a skin disease. In the Western countries (e.g., Switzerland, Austria, the United Kingdom), the ticks are more likely to carry Borrelia garinii, which causes primarily a neurologic disease. Lyme endemic areas have been identified as far west as Portugal and all the way east to Turkey and north to Russia (Mead 2015).

While similar across countries and continents, there are also important differences. In Europe, for example, there are three primary genospecies, while in the United States one genospecies causes most cases of Lyme disease. In Europe, there are more diverse skin manifestations, such as a chronic late-appearing rash called erythema chronicum atrophicans or an earlier blue-red rash or nodule called Borrelia lymphocytoma, which most often appears on the earlobe of children or nipple of adults. These different clinical manifestations reflect genetic differences in the species of the spirochete that causes Lyme disease. Not only are the initial and later-stage manifestations somewhat different among the United States and other countries, but these genetic differences also mean that diagnostic tests that work in one location may not work as well in another. Additionally, there are questions regarding whether the treatment response to antibiotics differs based on the infecting genospecies. For example, in Europe it has been reported that oral doxycycline is just as good as intravenous ceftriaxone for neurologic Lyme disease. Is this applicable to neurologic Lyme disease in the United States as well? We do not yet know, as these studies have not yet been done.

Consider the following case of a woman from the northeastern United States. While the initial course was typical, the subsequent symptoms led to important questions.

CASE 1. Lyme Disease with Rash and Disseminated Symptoms

A forty-year-old previously healthy woman living in a Lyme endemic area developed diffuse muscle aches, palpitations, and fatigue about four days after pulling weeds from her garden. Although she felt feverish, her temperature was normal. Two days later, her spouse noted an apple-sized rash on the back of her leg, followed a few days later by other round rashes elsewhere on her body. These rashes started small and grew larger, and they were not itchy. She also noted that normal light started to bother her—the television screen appeared abnormally bright and sunlight hurt her eyes such that she kept the window shades down during the day. Sounds in stores were uncomfortably loud. Chewing became difficult because of jaw pain. Headaches emerged. She felt dizzy at times and had trouble reading. About four weeks after the onset of symptoms, Lyme disease was diagnosed based on the rash and fully positive blood tests for Lyme disease (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay [ELISA] and Western blot—both IgM and IgG). After treatment with three weeks of doxycycline, the rashes, jaw pain, and headaches resolved, but her fatigue was still quite dense and she noticed cognitive problems emerging, such as problems with short-term memory and word-finding.

Comment: This woman did not recall a tick bite, but she had been gardening in a tick-infested area just days before development of the typical round red expanding rash of Lyme disease. The bacteria that cause Lyme disease, known as B. burgdorferi, were transmitted to her through the bite of a tick she hadn’t seen; the spirochetes then spread through her skin and into her bloodstream, thereby reaching other parts of her body and causing rashes elsewhere. Had she seen the initial tick bite and removed it within the first twenty-four to thirty-six hours of attachment, she most likely would not have contracted Lyme disease. The early flu-like symptoms were followed by headaches, sensory sensitivity, profound fatigue, and, later, cognitive disturbances. She received the standard course of antibiotic therapy for early Lyme disease. In most cases, when Lyme disease is treated early, the symptoms resolve completely and quickly. In this case of an individual with multiple rashes indicating dissemination of the infection, this course of antibiotic treatment led to a resolution of some but not all of her symptoms.

The woman asked, “What should I do next?” Should her doctor recommend that she wait several months, as complete resolution of symptoms after antibiotic therapy can take time? Should her doctor recommend a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) to look for evidence of central nervous system infection given the new onset of memory and word-finding problems and then possibly treat with intravenous antibiotics to ensure better penetration of antibiotics into the central nervous system? Or should her doctor recommend returning in four weeks to see if the symptoms have improved? If not improved after four weeks, would a second round of oral antibiotics be considered? She asks, “How do I know if I still have the infection in my body? Is there a blood test that will answer this question? I don’t like antibiotics, but if I need them I’ll take them.”

As this woman consults with other doctors, searches the Internet for answers, and listens to the advice of friends, she realizes that the tests are not as informative as she had hoped and that there are many different opinions about what she should do next. She becomes more confused. “Why do doctors not agree with one another? Whom should I trust? Which treatment path should I pursue?”

Lyme disease is often a short-lived illness that responds to early antibiotic treatment without any long-term problems. However, in some individuals—especially if the infection is not treated until months later—the response to antibiotic treatment is incomplete and symptoms linger or return. Among these individuals, the delay in treatment may contribute to a more chronic and serious illness. These patients in particular want to know more about how to interpret the diagnostic tests, which treatment options are best for the chronic symptoms, and the reasons for persistent symptoms. These questions are obviously of paramount importance. This book presents much of what is now known in each of these areas. However, before going further, we would like to put all of this in context by taking the reader on a rapid tour of the history of Lyme disease.

A BIRD’S EYE VIEW

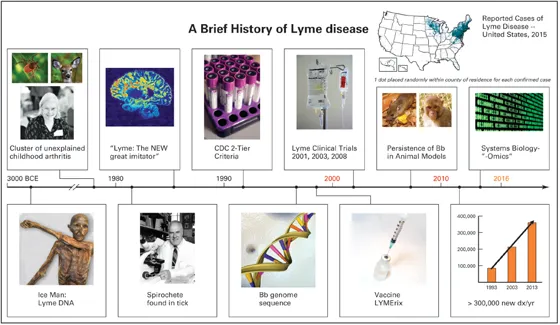

At times it is helpful to simplify. From our perspective, the history of Lyme disease can be divided into three periods.

| Period 1. 1970–1990 | Discovery, openness, rich clinical descriptions |

| Period 2. 1991–2007 | Epidemiologic surveillance, narrowed definitions, more specific tests, clarification of pathophysiology |

| Period 3. 2008–Present | Renewed openness and inquiry into multiple causes of persistent symptoms, discovery-based science and precision medicine tackle the illness |

The timeline depicted in figure 1.3 presents some of the key highlights of these three periods. While we will be discussing all of these highlights and others in greater depth in the subsequent chapters, we present them here briefly for the advantage of the bird’s eye view.

FIGURE 1.3

Counter clockwise from left: deer tick, courtesy of the CDC/James Gathany; deer, courtesy of Dr. Barbara Strobino; Polly Murray, courtesy of Dr. Kenneth Liegner; MRI scan Multiple Sclerosis, cour...