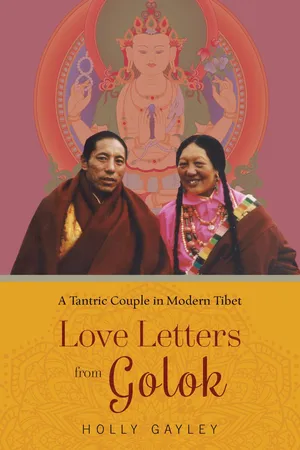

![]()

ONE

Daughter of Golok

Tāre Lhamo’s Life and Context

THE DAUGHTER OF Apang Terchen, a prominent treasure revealer in Golok, Tāre Lhamo was identified as an extraordinary child in prophecies surrounding her birth. Prior to pregnancy, her mother, Damtsik Drolma, received pronouncements from two local Buddhist figures that they planned to reincarnate in her home.1 When Tāre Lhamo was just an infant, her family went on pilgrimage to Lhasa, where the eminent Dudjom Rinpoche Jigdral Yeshe Dorje (1904–87) recognized her as an emanation of Yeshe Tsogyal, a figure central to treasure lore as the Tibetan consort of the eighth-century Indian tantric master Padmasambhava, and Sera Khandro (1892–1940), a female tertön from the previous generation in Golok.2 The former identification was pivotal to the role that Tāre Lhamo later claimed through her treasure revelations, which are understood to be teachings received directly from Padmasambhava or a comparable figure in a previous life, and the latter gave her an immediate female antecedent of regional prominence, even through Sera Khandro would have still been alive when Tāre Lhamo was born (1938). The combination of her birth into the religious elite of Golok and early recognition of her emanation status allowed Tāre Lhamo access to esoteric teachings in the male-dominated religious milieu of Golok and paved the way for her to become a Buddhist teacher of considerable renown, alongside Namtrul Rinpoche later in life.

Despite her exalted status from birth, one peculiarity of Tāre Lhamo’s life story is that it rarely stands alone in published accounts.3 In her namthar, Spiraling Vine of Faith: The Liberation of the Supreme Khandro Tāre Lhamo, her life is refracted through a host of female figures—divine, mythic, and human. In the opening verses of praise, she is identified with the enlightened female deities Samantabhadrī, Vajravārāhī, and Sarasvatī, and her namesake, the female bodhisattva of compassion Tārā, is also invoked. Beyond that, the first half of the text consists of extended excepts from the life stories of two female predecessors, Yeshe Tsogyal and Sera Khandro,4 one of the figures who reportedly approached Damtsik Drolma to announce her reincarnation plans. Only after that, halfway through, is there finally an account of Tāre Lhamo’s own life. It begins with her religious training in youth, briefly mentions her first marriage to a scion of the Dudjom line, and then presents a series of miracle tales used to narrate her twenties and thirties, during the socialist transformation of Tibetan regions in the Maoist period. Then her namthar abruptly ends. The latter part of her life, in which she traveled and taught extensively with Namtrul Rinpoche, is subsumed into his namthar, Jewel Garland, in which Tāre Lhamo serves as a joint protagonist.5

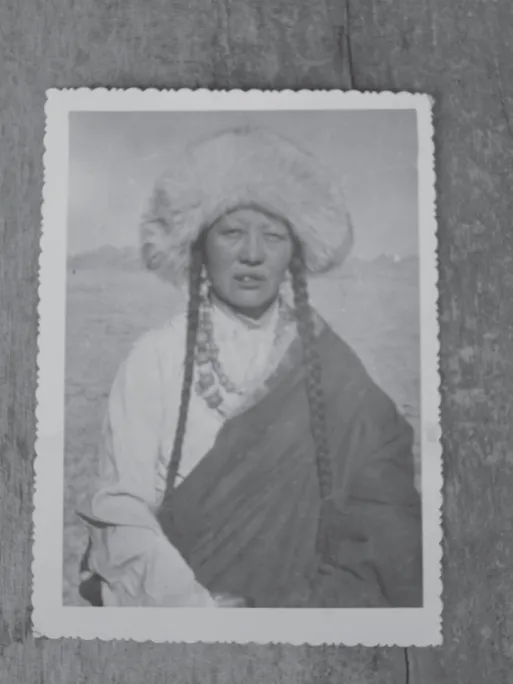

1.1 Khandro Tāre Lhamo in the late 1970s. Original photographer unknown.

What can learn about Tāre Lhamo herself, when the hagiographic construction of her identity is so deeply relational? Rather than producing an “imaginary singularity” of the autonomous individual,6 Tibetan life writing frequently constructs the identity of a Buddhist master as composite, an amalgam across many lifetimes. Janet Gyatso has highlighted the importance of such “connections” with respect to the lives of treasure revealers, who draw on past life associations to legitimate their revelations, while Sarah Jacoby has drawn attention to the importance of the “relational self” in autobiographical writings by Tibetan women.7 Spiraling Vine of Faith represents somewhat of an extreme case, given the extent to which it emphasizes Tāre Lhamo’s identification with female antecedents in the extended preamble to her birth, taking up half of her namthar and threatening to overwhelm her own story. In line with this, the correspondence between Tāre Lhamo and Namtrul Rinpoche also features a relational conception of identity, constructing their public personae as a couple through a series of past life connections across time and space. This raises a conundrum: where is the locus of agency within the proliferation of past lives? To what extent does such a relational identity enhance or delimit agency, specifically for Tibetan women who have managed to make it into the literary record with a significant legacy of writings by or about them?

Just as Tāre Lhamo begins to come into focus as a remarkable woman in Spiraling Vine of Faith, the namthar ends, and her religious career is subsumed into Jewel Garland, where her identity becomes fused with that of Namtrul Rinpoche. Here the “eminent couple” (skyabs rje yab yum) is the protagonist, acting in concert and sometimes even speaking in one voice. A comparable interweaving occurs in their abbreviated namthar, Jewel Lantern of Blessings, though in that case their activities as a couple are embedded in her story. Likewise, in their correspondence, her voice intermingles with that of Namtrul Rinpoche as they negotiate the terms of their union and construct their identity as a couple based on visionary recollections of their past lives together and prophecies about their future revelations. What we find in these published literary sources, epistolary and hagiographic, is neither the autonomous individual of Western humanism nor the fragmentary self (and decentered agency) of poststructuralism.8 Rather, her identity is composite, densely layered, and accretive in nature, embedded in a web of connectivity.

In Spiraling Vine of Faith, this connectivity entails her simultaneous identification with and reliance on female deities, producing a paradox in the representation of female agency. Typical of Tibetan hagiographic literature more broadly, Spiraling Vine of Faith portrays female agency as the domain of ḍākinīs, a class of female deities who are central to Buddhist tantric iconography, ritual, and visionary experience and who can also be embodied by actual women like Tāre Lhamo.9 In her namthar, she is aided by the ḍākinīs, said to be continually by her side, and is herself cast as a living khandroma, the Tibetan term that translates the Sanskrit ḍākinī. Thus, on the one hand, Spiraling Vine of Faith features a panoply of female deities who appear in visions to Tāre Lhamo and her predecessors to offer inspiration, advice, and prophecies. And on the other hand, Tāre Lhamo is presented as a ḍākinī-in-action, performing miraculous feats on behalf of her local community during the turbulent decades of the Maoist period, when Tibetans faced severe repression under Chinese Communist rule. This slippage between the representation of exceptional historical women and the deflection of agency to a divine source, I argue, both authorizes and delimits the scope of female agency.

This chapter explores issues of gender and agency in the life of Tāre Lhamo as written and lived in the social context of the tight-knit treasure scene in Golok. After providing a brief summary of her life, I shift between literary text and social context to examine how a cultural space is created for female religious authority in a male-dominated milieu. I ask whether Tāre Lhamo’s religious authority derives primarily from links with men in Golok’s treasure scene, especially her prominent father, or from her associations with female antecedents in the symbolic system of Tibetan Buddhism. Addressing this question takes us into the complex politics of reincarnation and overlapping networks of clan, lineage, and monastic affiliation in Golok. It also takes us into the literary world of namthar through a less commonly explored gate. While Tibetan autobiography has been the subject of several recent studies,10 this chapter explores the genre of namthar in a hagiographic key, as an idealized account of the life of a Buddhist master narrated by a devoted disciple.11 I am particularly interested in the impact of third-person narration on the construction of female agency, which I will later contrast with Tāre Lhamo’s own voice and self-representation in her epistolary exchanges with Namtrul Rinpoche. Spiraling Vine of Faith itself has several discernible vantage points due to the composite nature of the text, which offer a fertile basis for comparison and create a synthesis within the work to construct Tāre Lhamo unequivocally as a Buddhist tantric heroine.

By delving into issues of gender and agency, this chapter provides the necessary background to understand how Tāre Lhamo served as a heroine for her local community during the socialist transformation of Tibetan areas and went on to become an important Buddhist leader in Golok during the post-Mao era. While her relational and composite identity might seem at first to diffuse her agency, her association with the figure of the ḍākinī became important to narrating a devastating chapter of Tibetan history in a redemptive key. Relational and composite identity is likewise central to the ways that Tāre Lhamo and Namtrul Rinpoche conceived of their shared destiny in their correspondence and imagined the possibility of revitalizing Buddhist teachings, practices, and institutions in the wake of the Cultural Revolution. Furthermore, re-creating a web of connectivity is central to the hagiographic portrait of the couple in Jewel Garland, which highlights their connections to people and places as the very means by which they reconstituted Tibetan communities and Buddhist networks during their extensive teachings and travels in the 1980s and ’90s.12 To recover subaltern pasts, we first need to gain a footing in the literary world of namthar and the social context of Golok, beginning with the ways that religious identities are formed and how gender and agency operate in those settings.

Life of Tāre Lhamo

This brief overview of Tāre Lhamo’s life in historical terms is a summary of what I have garnered from multiple sources: the namthars and letters introduced in this book, interviews with people close to Tāre Lhamo throughout Golok,13 audio-visual materials produced by Nyenlung Monastery, and other written accounts, such as the biographies of related figures and local monastic histories. I present the facts as best as I have been able to discern them rather than analyze stories (literary or oral) about her as representations—my tack for the bulk of the book.

Tāre Lhamo was born in 1938, the daughter of Apang Terchen Orgyan Trinle Lingpa (1895–1945), alias Pawo Chöying Dorje,14 a prominent tertön in Golok from the Apang family with an illustrious past life pedigree, and Damtsik Drolma, the daughter of a local chieftain who was also regarded as an emanation of Yeshe Tsogyal. Apang Terchen’s homeland was Dartsang, but like most religious figures in nomadic Golok, he was highly mobile, shifting his residence regularly between what are today Padma County in Qinghai Province and Serta County in Sichuan Province. At the time of Tāre Lhamo’s conception, Apang Terchen and Damtsik Drolma were staying at the sacred mountain Drongri, the abode of a local protector in the region. However, her birthplace was closer to Tsimda Gompa, the monastery in Padma County that Apang Terchen founded, in a valley between gently rolling hills called Bökyi Yumo Lung. Tāre Lhamo was the fourth of five children and the only girl among them.15

Because of her elite status, Tāre Lhamo had considerable access to esoteric teachings in her youth. She began her religious training under her father and received the transmission for the entirety of his treasure revelations at a young age. In 1945, he passed away when she was only nine years old (by Tibetan reckoning), but remarkably, not before they had revealed a treasure together.16 During the rest of her youth, she traveled extensively on pilgrimage throughout the region of Golok, accompanied by her mother, and received teachings from many of the eminent religious figures of her day, including Rigdzin Jalu Dorje (1927–61), the fourth in a line of Dodrupchen incarnations,17 and Dzongter Kunzang Nyima (1904–58), the grandson of Dudjom Lingpa. As the daughter of a tertön, Tāre Lhamo was able to join the encampments of Nyingma masters, where she participated in religious gatherings, receiving initiations and instructions in various tantric ritual cycles, such as the Nyingtik Yabshi (Snying thig ya bzhi). Tāre Lhamo became a close disciple of Dzongter Kunzang Nyima,18 who served as her principal teacher, giving her the empowerment, authorization, and instructions for his treasures and formally investing her as the trustee (chos bdag) for his sādhana cycle of Yeshe Tsogyal.

1.2 Statue of Apang Terchen in the Vajrasattva temple at Tsimda Monastery.

In 1957, at the age of twenty, Tāre Lhamo joined the encampment of Dzongter Kunzang Nyima and married his son Mingyur Dorje (1934–59), who was nicknamed Tulku Milo.19 The encampment, which served as Dzongter Kunzang Nyima’s main residence for more than two decades, was located at Lunghop (also known as Rizab), at the base of a mountain outside of Dartsang. In the previous generation, it was common for a Buddhist master in Golok to attract students to a hermitage at a far remove from other habitations. As disciples gathered around a charismatic teacher, an encampment (sgar) would form with no permanent structures, only the black yak-hair tents used by nomads as homes. According to his son, Pema Thegchok Gyaltsen, several thousand disciples gathered around Dzongter Kunzang Nyima in this encampment as a fluid and vibrant community.20 As family members, the young couple formed part of an inner circle to whom Dzongter Kunzang Nyima bestowed esoteric Dzogchen teachings from his own treasure corpus (gter chos) and that of his grandfather Dudjom Lingpa, of whom he was recognized as the speech emanation (gsung sprul).21

Tāre Lhamo and Tulku Milo lived at Rizab, and apart from the general atmosphere of the encampment, it is difficult to know what their short time together entailed except that she gave birth to a son. Spiraling Vine of Faith dedicates a paragraph to Tāre Lhamo’s first marriage but never mentions her son.22 I heard only one story about her marriage with Tulku Milo from one of her close friends. It seems too frivolous to be worthy of inclusion in a namthar but gives some sense of the humor and affection between the young couple. One time ...