![]()

1

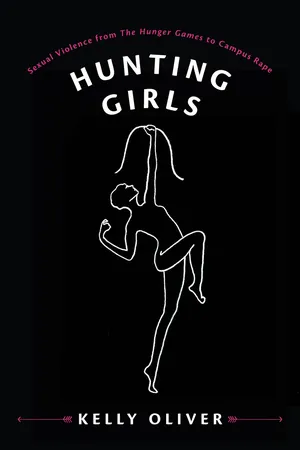

A PRINCESS IS BEING BEATEN AND RAPED

STRONG GIRL PROTAGONISTS IN Young Adult literature and films such as Bella Swan in Twilight, Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games, and Beatrice “Tris” Prior in Divergent give as good as they get. Still, in these contemporary fairytales, our princesses are being beaten, bloodied, bruised, almost killed, and sometimes even sexually assaulted. The rape of princesses, however, is as old as princesses themselves. And sexual assault in film is nothing new.1 Hollywood has always banked on representations of violence toward women. Now, the women are just girls; and the abuse of teenage girls, beaten and bloodied in films, is aimed at younger and younger audiences. With film, fantasies of violence toward girls and women take on a visual dimension that further eroticize and anesthetize images of abuse toward girls. Insofar as these images of girls being beaten are staged and shot in the same way as other violent images in blockbuster films, they become part of the entertainment.2

Certainly, within these retold fairytales, for girls (and boys) coming-of-age is brutally violent. The transition from girlhood to womanhood is a violent initiation, which in some ways may mirror the real-world experience of girls, who, statistically, face a strong chance of becoming the victims of sexual abuse, violence, and rape.3 Although my analysis is not directed at hookup culture, or even rape culture, per se, it interacts with those notions.4 Specifically, I consider issues of power, control, and danger, as they play into contemporary manifestations of sexuality. In this chapter, I argue that these filmic fantasies perpetuate, justify, aestheticize, and normalize violence toward girls. In addition, some of these contemporary fantasies take us back to medieval notions of consent as the purview of men only, and thereby serve as warnings to girls and young women coming-of-age in a world of affirmative consent apps for cellphones, and party rape creepshots photographed, or recorded, on those same cellphones. Here, tracing the fantasy of consent on the part of sexual predators, along with the drugging and raping of unconscious girls, from the fourteenth-century tale of Sleeping Beauty to its contemporary retellings in Disney’s Maleficent (2014) and Divergent, to the wildly popular Fifty Shades of Grey wherein lack of consent is hot, it becomes clear that in terms of sexual politics, in many ways, we are still in the Middle Ages.

THE RAPE OF SLEEPING BEAUTY

Once upon a time, there was a tale of a beautiful princess who was drugged unconscious and raped. What could be an entry in too many a college girl’s diary is the medieval tale of Sleeping Beauty, familiar to pop culture through Disney without the drugs or rape—that is, until 2014’s dark retelling in Maleficent (played by Angelina Jolie). The myth of Sleeping Beauty, awakened from sleep by the kiss of her prince, is the quintessential rape fantasy. Revisiting this fairytale and its history is apt considering the widespread use of rape drugs on college campuses, drugs that render girls unconscious or put them to sleep.5 What are we to make of this desire to kiss or have sex with—that is to say, rape—an unconscious “dead” girl? For starters, it is a desire that takes us back to the fourteenth century at least, and may be the ultimate power trip for sexual predators.

The fantasy of sex with an unconscious girl is centuries old, mythical even, with its first recorded roots in an anonymous fourteenth-century Catalan story entitled Frayre de Joy e Sor de Plaser (Léglu 2010:102). In this version of the fairytale, after the beautiful virgin daughter of the emperor of Gint-Senay dies suddenly, her parents place her in a tower accessible by a bridge of glass. Among the young men attracted to the tower, Prince Frayre de Joy, son of King Florianda, convinces a magician to give him the means to reach the tower. When he sees the sleeping beauty’s smiling face, he “has sex repeatedly with the corpse” and gets her pregnant. Nine months later, she gives birth to a son who suckles at her dead breast. The prince wants to marry Sor de Plaser and makes a bargain with the magician, who brings the girl back to life in exchange for his kingdom. At first, the girl refuses to consent to the marriage because the prince raped her. But once she learns that the father of her child is the noble Frayre de Joy, she agrees and the prince becomes the successor to her father as emperor of Gint-Senay (Léglu 2010:102).

In her interpretation of the poem, Catherine Léglu describes how the young prince attributes consent to Sor de Plaser by kissing her a hundred times until her lips move in response, and then exchanging his ring for hers as a promise of betrothal to justify the rape (2010:106–107). She maintains that, throughout the poem, the prince sees signs of the dead girl’s active consent. This line from the poem indicates the level of the prince’s hallucinations of consent: “And it seemed to him that she was smiling gently at him, and that she was satisfied” (2010:106). “The text,” says Léglu, “endorses his forceful reinterpretation of her dead body as a consenting partner with a proverbial expression” containing the girl’s name, Plaser or pleasure: “Pleasure loves, pleasure desires; thinking brings worry, pleasure guides” (2010:106–107). At the time that this fairytale was written, it was widely held that women could not conceive without an orgasm. Thus, Sleeping Beauty’s pregnancy would be proof of her consent.6 This absurd view has recently reappeared in the political arena after the Republican representative from Missouri, Todd Akin, said in an interview, “‘legitimate rape’ does not lead to pregnancy. . . . If it’s a legitimate rape, the female body has ways to try to shut that whole thing down” (Franke-Ruta 2012).

Léglu discusses another Sleeping Beauty tale, cantare of Belris, from fourteenth-century Italy, wherein the girl is sleeping under an enchantment rather than dead. In this tale, Prince Belris is tasked with retrieving a falcon. While out slaying dragons, he has sex with another woman along the way. Eventually, he finds a sleeping queen, whom he rapes, leaving her a note with instructions for the name of the son she just conceived. The birth of the son awakens the sleeping queen and she commands her army to find Belris and makes him marry her. His other mistress kills herself and leaves her own son orphaned. In another version of this medieval tale, believing his daughter Clarisse is cursed, a father locks her in a garden with her governess to protect her. The girl falls ill and the nurse gives her wine to make her well. The girl goes into a drunken stupor and the governess goes off to Mass. A passing prince comes upon her, sees her alone in the garden, and taken by her beauty, he kisses her. Like Frayre de Joy, he interprets the girl’s lack of response as consent. Since the girl doesn’t resist, he rapes the drunken girl (Léglu 2010:121).

These tales morph into the medieval courtly romantic poem Perceforest wherein a princess, Zellandine, falls in love with a prince, Troylus, who must perform courageous feats to win her hand. While he is off on his adventures, she falls into a deep sleep from an enchantment. Upon his return, he rapes her while she is sleeping and impregnates her. He removes the flax from her finger that caused the enchantment and they marry. The question, of course, is why he didn’t wake her before having sex with her. In these tales, the fantasy of the sleeping or dead girl not only ensures the lack of resistance to sex but also engenders illusions of consent, and even sexual satisfaction and love, on the part of the unconscious girl. Sex, consent, and satisfaction are all the property of men and their fantasy projections onto incapacitated girls and women. This medieval fantasy of consent is echoed in a remark made by one of the boys involved in the gang rape of an unconscious high school girl in Steubenville (Ohio), who said, “It isn’t really rape because you don’t know if she wanted to or not” (Ley 2013). The illusion that unconscious girls may want sex, even enjoy it, is still with us. From fairytales to pornography, popular culture is filled with girls and women, unconscious or sleeping, “enjoying” nonconsensual sex. And until we change our fantasies, it is going to be difficult to change our realities.

A PRINCESS IS BEING DRUGGED

Starting with Charles Perrault’s (1608–1703) La Belle au Bois Dormant, “Sleeping Beauty in the Wood,” modern versions of the tale displace the prince’s rape of the unconscious girl with the prick from a spindle, followed by a kiss from the prince. In Perrualt’s version, and in the Brothers Grimm’s Dornröschen or “Little Briar Rose,” a beautiful princess falls under a sleeping enchantment and is awakened by a kiss from a handsome prince. The issue of consent falls away as an explicit part of the narrative, and the girl wakes up to the man of her dreams, who breaks the spell, and then marries her. With Walt Disney’s animated version of the classic fairytale (1959), Sleeping Beauty is named Aurora and the rape from earlier versions is transformed into “true love’s kiss.” In this familiar version, Aurora is cursed at her christening by an evil fairy named Maleficent: while she will grow up with grace and beauty, on her sixteenth birthday Aurora will prick her finger on a spinning wheel and die. Another fairy modifies the curse so that she doesn’t die, but only falls into a deep sleep. Just before Aurora’s sixteenth birthday, she meets Prince Philip in the woods, not knowing, of course, that he is a prince. It is love at first sight. Soon after, she pricks her finger and lies sleeping in the castle. Prince Philip must overcome obstacles, most especially Maleficent, to reach Aurora. But after slaying Maleficent, who has transformed herself into a dragon, he wakes Sleeping Beauty with true love’s kiss, and they live happily ever after. It is noteworthy that in this version, Sleeping Beauty is acquainted with the prince. He is not a stranger who happens upon the scene. Still, without her consent, he kisses the unconscious girl, whom he loves.

The repression of the rape theme in Sleeping Beauty, specifically in Disney’s 1959 film, returns with a vengeance in Disney’s recent retelling of the tale, Maleficent (2014). In this recent version of Sleeping Beauty, there is a symbolic rape after Maleficent is drugged unconscious by her lover. Indeed, the film revolves around this traumatic moment, which could be interpreted as the rape of a woman intentionally rendered unconscious by drugs administered by her beloved. The film starts with Maleficent’s backstory as told in voice-over by a young woman whom we learn at the end of the film is Sleeping Beauty, also known as Aurora. As a winged girl fairy, Maleficent falls in love with a human boy named Stephan. Rather than give her a ring, Stephan proves his love to her by throwing away his only possession in the world, a steel ring that burns Maleficent when it touches her skin. On her sixteenth birthday, Stephan gives her the gift of “true love’s kiss.” But as he grows up, Stephan becomes more interested in power and fortune than love; eventually he hunts Maleficent (Angelina Jolie) in the hopes of becoming heir to the throne. For the dying king has promised his throne to whoever can kill the winged beast.

Stephan (Sharito Copley) goes back to the enchanted forest, the Moors, land of the fairies, and calls out to Maleficent, who answers. They spend the night together, seemingly rekindling their love. Stephan gives Maleficent something to drink out of a flask, as she lovingly puts her head on his shoulder. Drugged, Maleficent falls into a deep sleep and Stephan pulls out his dagger to kill her. When he looks upon his sleeping beauty, he can’t go through with it. Instead, he cuts off her wings and takes them as a prize, as evidence that he “vanquished” Maleficent. When she awakens, wingless and alone, betrayed by her true love, she cries out in anguish. Her loving and trusting personality changes into bitter vengefulness and sorrow. We could say, like most victims of sexual assault, she suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. The trauma of her symbolic rape drives the rest of the plot.

Unlike other contemporary versions of the Sleeping Beauty/Snow White story that displace the violence of the rape of an unconscious girl onto true love’s kiss, Disney’s 2014 version shows the symbolic rape of Maleficent. This symbolic rape is also date rape insofar as Stephan tells her he loves her, then drugs her, and violently assaults and dismembers her. Maleficent’s “evil” is attributed to her trauma, and her attempts to avenge Stephan’s brutal betrayal. When King Stephan and his queen have a baby girl, Maleficent attends the christening uninvited. She curses the girl to grow in grace and beauty until her sixteenth birthday when she will prick her finger on a spinning wheel and die. Under protests from King Stephan and the other fairies, Maleficent amends the curse so that Aurora will not die but rather fall into a deep sleep that can only be awakened by true love’s kiss, an explicit jab at Stephan’s past false promises of true love and true love’s kiss. No longer believing in the possibility of true love, Maleficent is confident that she has cursed the girl to sleep forever.

The king entrusts Aurora to three fairies to raise her, away from the castle and away from any spinning wheels. Maleficent watches Aurora grow, and she saves her from the ineptitude of her caregivers, who are too self-absorbed to take care of the child. As a teenager, Aurora (Elle Fanning) says she wants to leave her “aunties” and come to live with Maleficent, whom she calls her “fairy godmother.” Touched, Maleficent tries to break her own curse, but can’t. As the story goes, just before her sixteenth birthday, Aurora meets Prince Philip in the woods. While they don’t declare their love, they are obviously interested in each other. When she tells her aunties that she is leaving them to live in the Moors, they spill the beans about her father, King Stephan, and her home, the castle. Aurora goes to the castle, where Stephan locks her up to prevent the curse from coming true. Alas, in a cursed trance, Aurora finds a spinning wheel, pricks her finger, and falls into a death-like sleep. Hoping that Prince Philip can deliver true love’s kiss and break the spell, Maleficent and her trusty familiar, a crow named Diaval, drag the prince to the palace. The three fairy aunties beg him to kiss Aurora. At first, he demurs, saying that he doesn’t know her well enough. But he never mentions that she is unconscious, and therefore cannot consent, or that lack of consent might be a reason to think twice about kissing her. Of course, as we’ve seen in earlier versions of the fairytale, lack of resistance has been interpreted as consent. He cannot deny she is beautiful, or that he wants to kiss her, so eventually he does. But the spell is not broken and Aurora remains asleep.

Lamenting her curse and what she’s done to her daughter surrogate, Maleficent asks for Aurora’s forgiveness, which she says she does not deserve. She kisses Aurora on the forehead, and sure enough, the princess wakes up. True love’s kiss is not delivered by the prince, or by the lover, but rather by the mother, the fairy godmother. The bond between mother and daughter brings Aurora back to life. Aurora goes back to the Moors with Maleficent where presumably they live happily ever after. Because it’s Hollywood and Disney, the heterosexual couple must be reunited at the end, and Prince Philip has joined them in the Moors. This is also the case in the popular animated film Frozen (2013), where Princess Anna and Kristof end up together, even though Elsa delivers the true love’s kiss that awakens her frozen sister Anna. Love between sisters, although stronger than that between lovers, is reinscribed at the end of the film within the heterosexual narrative of prince and princess living happily ever after. So too in Maleficent, while true love is that between mother and daughter and not between prince and princess, the prince makes another appearance at the end—although in this case the movie ends with Maleficent flying high above the clouds on her newly attached wings, which were freed by Aurora after she was awoken from the spell.

The film ends with the same voice-over with which it began, telling us that Maleficent is both the hero and villain of the story. The narrative, however, tells a different story, one where King Stephan is the villain, who lies, drugs, and symbolically rapes his “true love” to gain fame and fortune. He dies trying to kill Maleficent. And presumably, the union between Aurora, crowned queen of the Moors by Maleficent, and Prince Philip will unite the two kingdoms of fairies and humans, a union whose true bond has already been forged between fairy godmother Maleficent and her beloved human “daughter” Sleeping Beauty. Although Aurora, Elsa, and Anna are beautiful feminine princesses, shown wearing familiar flowing dresses and long flowing locks, they are extravagant girls insofar as they give priority to their love for the women in their lives over finding or keeping Prince Charming. Indeed, for both Anna and Maleficent, “Prince Charming” turns out to betray them for fame and fortune. Moreover, Elsa and Maleficent reject heterosexual romantic love entirely in favor of love relations with the women in their lives. Love between wo...