![]()

PART I

Why Design Thinking?

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Catalyzing a Conversation for Change

The Case of the Smoking Cucumber Water

The article in the Washington Post seemed innocuous. It described high hopes for the 2012 opening of the new innovation lab at the US Office of Personnel Management (OPM), the agency charged with overseeing the education and development of all federal employees. Located in the subbasement of OPM’s DC headquarters, the Lab@OPM was hardly sumptuous, occupying just three thousand square feet. Renovation costs barely topped $1 million (not enough to even register as a decimal point of OPM’s $2 billion budget that year), and almost half of that was to remove the asbestos in the ceiling. Total headcount was six employees.

But the article’s passing reference to a pitcher of cucumber water apparently attracted the unwanted attention of the House of Representatives’ Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, which formally requested that the Government Accountability Office (GAO) conduct a full audit of the year-old lab. For the next nine months, lab staff spent much of their time talking to auditors rather than encouraging innovation. Eventually, the GAO audit produced a largely favorable review of the work of the lab, but the only widely publicized finding was the GAO’s criticism that the lab had failed to implement a “rigorous evaluation framework” in its less than eighteen months of existence. The Post’s “Federal Insider” columnist reported this while ridiculing the “Silicon Valley buzzwords” behind the vision of the “so-called innovation lab.”

Amid the hoopla, it was overlooked that a lab staff member had, in fact, purchased that cucumber with his own money at Safeway and had cut it up himself to add to the tap water in the pitcher. And in the background was general frustration with the OPM in other areas, like retirement claims processing and security clearances. “It gave them their shot at us,” one lab staffer commented ruefully.

Doesn’t that just say it all about the challenges of doing innovation work in the social sector, of trying to design for the greater good?

Good work by dedicated people gets caught in the cross fire of politics and media, the right intentions and their complex reality sidelined by a combination of circumstances that few in the business sector would ever deal with.

The cucumber water story has a surprisingly happy ending. The GAO accountants in charge of the audit quickly grasped the challenging nature of the Lab@OPM’s work and were impressed. The extraordinarily resilient lab staff soldiered on to make significant contributions to the state of innovation in the federal government, which they continue today.

But when you talk to government innovators in DC, you can still sense a kind of posttraumatic stress syndrome, traceable back to that cucumber water, just below the surface. We have no way to know how many potential innovations in Washington have been lost to the fear of audits or public criticism.

We live in a world of increasingly wicked problems. Nowhere are they more evident than in the social sector. Whether we look at private or public efforts, across sectors like health care, education, and transportation, at the global or local level, organizations of all sizes and stripes struggle with thorny issues:

• stakeholders who can’t even agree on the problem, much less the solution;

• employees who are reluctant to change behaviors and take risks, who are often rewarded for compliance rather than performance;

• decision makers who have too much data, but little of the kind they need;

• leaders who are more likely to have short tenures and whose every move is scrutinized by funders, politicians, bureaucrats, and the media; and

• users of their services—students, patients, customers, citizens—whose expectations are sometimes rising as fast as resources to meet them are declining.

And to face this scenario, would-be innovators are armed with an outmoded tool kit premised on predictability and control, optimized for solving tame problems, in a world that offers fewer and fewer of them. Our goal in this book is to offer a new set of tools—ones better suited to the complexity and messiness of the challenges that social sector innovators face. Standing still is no more an option in the social sector than it is in the for-profit world. Innovation is an imperative.

THE LAB@0PM

The Lab@OPM has gone on to become a driving force behind innovation in the US federal government. We think of it as patient one in the viral spread of design thinking in DC—it is where innovators caught the fever for human-centered work. Scratch the surface of almost any interesting innovation success story across a wide variety of government agencies in Washington and you’ll find the lab’s guiding hand. The seed for the lab was planted in 2009, when President Obama appointed John Berry as director of the OPM and gave him the mandate to “make government cool again.” As the government’s chief “people person,” Berry was responsible for recruiting and developing almost 2 million federal employees. Berry brought a young Stanford grad, Matt Collier, on board to help in this effort.

In 2010, they took a tour of Silicon Valley, visiting the usual haunts—Google, Facebook, IDEO, and Kaiser Permanente’s Garfield Innovation Center. All of these companies had carefully architected their work spaces to support and encourage collaboration. “They were the kind of places that made you want to come to work,” Matt observed. When the OPM team thought about what they wanted to bring back to the East Coast, the notion of space and the IDEO-inspired design thinking approach were at the top of their list. As he explained:

We didn’t want to create just another meeting space. It was more about what we wanted to do in the space—to try to build a design thinking practice, to build a little IDEO inside of government, to bring that capability in-house. It was set up like a teaching hospital: we will do some teaching, but we will also do some application.

The lab staff selected LUMA Institute as their partner. They were drawn to LUMA’s reputation as an education company whose goal was to build capacity in human-centered design for individuals, teams, and organizations.

The lab has survived—in fact thrived—despite the GAO audit during its infancy and the change of senior leaders at OPM. Matt has a theory why:

It began as a political appointee–driven initiative that was rightly and appropriately embedded into the bureaucracy. The reins were handed over to the senior career leadership—not in a burdensome way but in a way where they wanted those reins. And everyday employees within the lab’s orbit were equipped and, indeed, expected to apply design thinking in service of their work and that of their colleagues. Because of that, the lab has survived. That was a huge success. Had we not given leadership over to career executives, the lab and all of the design thinking activities that went along with it could have easily gone by the wayside.

In facing challenges both obviously large (fighting hunger and poverty, encouraging sustainability) and seemingly smaller (getting invoices paid on time, increasing blood donations, decreasing hospital patient stays), social sector innovators are deciding that design thinking has the potential to bring something new to the conversation. They are bringing together people who want to solve a tough problem—not hold another meeting—in a world where forming a committee can be seen to count as action.

Design thinking is being used today in organizations as diverse as charitable foundations, social innovation start-ups, global corporations, national governments, and elementary schools. It has been adopted by entrepreneurs, corporate executives, city managers, and kindergarten teachers alike. In just a small sample of the stories we will discuss in this book, we see it helping impoverished farmers adopt new practices in Mexico, keeping at-risk California teenagers in school, reducing the frequency of mental health emergencies in Australia, and helping manufacturers and government regulators in Washington find common ground on medical device standards. Across these vastly different problems and sectors, design thinking provides a common thread. Maybe we could even call it a movement.

The shift under way seems to us, in fact, much like the one that created the quality movement. In the same way that the arrival of Total Quality Management (TQM) revolutionized the way organizations thought about quality, design thinking has the potential to revolutionize the way we think about and practice innovation.

Let’s take a quick look at the quality parallel. TQM had a transformational impact and drove a paradigm shift (not a term to be used lightly) about quality, from the old quality assurance mindset (scholars call this Quality I) to a completely different conception of what quality meant and whose job it was (Quality II). In Quality I, quality was seen as the domain of a small group of experts. In Quality II, quality became everybody’s job, and TQM made that possible by providing a language and tool kit for solving quality problems, which everybody could learn. TQM democratized quality.

WHAT IS DESIGN THINKING?

Design thinking is a problem-solving approach with a unique set of qualities: it is human centered, possibility driven, option focused, and iterative.

Human centered is always where we start—with real people, not demographic segments. Design thinking emphasizes the importance of deep exploration into the lives and problems of the people whose lives we want to improve before we start generating solutions. It uses market research methodologies that are qualitative and empathetic. It is enthusiastic about the potential to reframe our definition of the problem and engage stakeholders in co-creation.

Design thinking is also possibility driven. We ask the question “What if anything were possible?” as we begin to create ideas. We focus on generating multiple options and avoid putting all our eggs in one particular solution basket. Because we are guessing about our stakeholders’ needs and wants, we also expect to be wrong sometimes. So we want to put multiple irons in the fire and let our stakeholders tell us which work for them. We want to manage a portfolio of new ideas.

Finally, the process is iterative. It conducts cycles of real-world experiments to refine ideas, rather than running analyses using historical data. We don’t expect to get it right the first time—we expect to iterate our way to success.

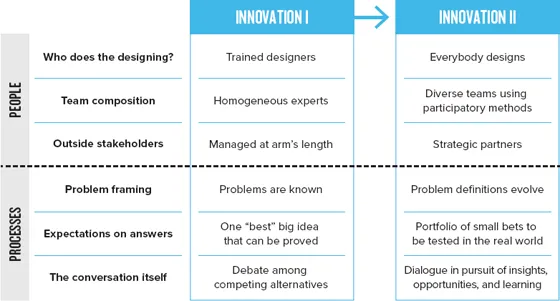

That same kind of revolutionary shift is under way today in innovation. Innovation I, the old paradigm, looks a lot like quality assurance. It is isolated in experts and senior leaders, decoupled from the everyday work of the organization. In Innovation I, innovation is about big breakthroughs done by special people. Design in the Innovation I world is mostly about aesthetics or technology.

The shift from Innovation I to Innovation II.

We are seeing the emergence of Innovation II, the democratizing of innovation. In this world, we are all responsible for innovation. Even the term itself has a new meaning. Innovation isn’t only—or even mostly—about big breakthroughs; it is about improving value for the stakeholders we serve. And everybody in an organization has a role to play. It is not that we no longer care about big, disruptive innovations or that we don’t still need expert innovators and designers—it is just that we acknowledge two truths: first, it is often impossible to tell early in the life of an innovation just how big or small it will someday be; and, second, many small things can add up to something big.

As Innovation II emerges, design thinking provides a common language and problem-solving methodology (as TQM did in quality) that everyone can use to help their organization more effectively accomplish key strategic objectives, whether those objectives involve traditional business outcomes like profitability and competitive advantage or social outcomes like reducing poverty or creating jobs. As organizations develop this organization-wide capability for innovation, they will enhance their ability to achieve their objectives by generating more innovative and effective outcomes and processes that create better value for the stakeholders they serve and that make the organizations more effective in meeting their missions.

Design thinking makes Innovation II possible by encouraging distinct shifts in mindsets and behaviors. These shifts impact the individuals, teams, and extended group of stakeholders who do the designing, the way in which they identify problems and seek solutions, and the basic nature of the conversation itself. It also involves changes in the organizational context to facilitate such work at the individual and team levels.

In the remainder of part 1 of this book, we provide an overview of what such a change looks like and how it impacts the behavior of the specific people involved. In part 2, we share ten stories from a broad cross section of organizations, which allows us to look in depth at the different roles design thinking can play. Part 3 contains a detailed, step-by-step walk through our own design thinking methodology, illustrated with a final story about a group of educators attempting their first project, which aims to provide a blueprint of how the complete end-to-end process looks in practice. The book concludes with some thoughts about how to build an organizational infrastructure to better support the democratizing of innovation.

As we get started, we first want to talk at a more strategic level about the differences we observe in Innovation I versus Innovation II organizations and why they matter. In the remainder of the book, we will look at how these new Innovation II mindsets and behaviors play out in innovation projects led by real people in real organizations.

It all starts with who does the innovating.

Who Gets to Innovate? Engaging New Voices

The most obvious marker of the transition to an Innovation II world is the question of who is invited to innovate—in other words, who designs? In Innovation I, innovation and design are the domain of experts, policy makers, planners, and senior leaders. Everyone else is expected to step away. This perspective was vividly illustrated by a comment made to us by the chief design officer of a large global corporation, who suggested that encouraging nondesigners to practice design thinking was like encouraging those without a medical license to practice medicine.

In Innovation II, the search for opportunities to innovate is everybody’s job, so everybody designs. Here, design is not primarily about the design of products or even user experiences; instead, design thinking is seen as a problem-solving process appropriate for use ...