- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This volume considers for the first time in a single collection this acclaimed, award-winning director's entire oeuvre, addressing and analyzing themes such as identity, family, and masculinity, supported by in-depth coverage of the generic and aesthetic aspects of DiCillo's distinctive and influential film style. Through detailed chapters on each of DiCillo's feature films, presented here is a candid look behind-the-scenes of both the American independent film industry - from the No Wave movement of the 1980s, through the Indie boom of the 1990s, to the contemporary milieu - and the Hollywood studio system. This study documents the writing, production, and release of every DiCillo picture, each followed by an extensive Q&A with the director. Also featured are exclusive interviews and commentary with many cast members and collaborators, and members of legendary rock group, The Doors. Films covered include Johnny Suede, Living In Oblivion, Box of Moonlight, The Real Blonde, Double Whammy, Delirious, When You're Strange, and Down in Shadowland.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Cinema of Tom DiCillo by Wayne Byrne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film Direction & Production. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film Direction & ProductionCHAPTER ONE

The Language of Dream: Deciphering DiCillo

At the age of twelve I discovered Johnny Suede, completely by accident. Up to that point I was an avowed action movie buff, worshipping at the altar of Steven Seagal, no less. One day in the video store I noticed an iridescently colored VHS case for a film with a striking picture of Brad Pitt sporting a huge pompadour. Something prompted me to rent the film.

I cannot underestimate the influence Johnny Suede had on me on that first viewing; it was a culture shock. It opened up to me the doors of cinema and all its varieties and possibilities. Films didn’t just have to be about violence and spectacle; they could be about you and me, or those people just over there. The raw human emotions of the film felt real and immediate, yet its surrealist aesthetic, absurd humour and haunting music gave it a sense of the peculiar and the exotic. The effect it had on me was hypnotic.

I immediately declared my unabashed belief of Johnny Suede to be the greatest film I had ever seen to anybody that would listen. I longed to experience more of this director Tom DiCillo’s work; his was an idiosyncratic vision that was completely and distinctively his. It felt like Johnny Suede was this little gem only I was privy to and I wanted to keep it, literally. Upon returning the video I proposed an offer to the clerk which would have resulted in the most expensive purchase in my life up to that point had he accepted: “I’ll give you thirty pounds for it!” Deep down I knew my proposition was going nowhere; the kid was a mere employee with no ability to make such executive decisions as turning a rental cassette into a retail one; nor did I actually have thirty pounds to give him should he accept my offer. It was more of a desperate, knowingly futile attempt by me to cling tangibly to this videocassette that reached into my soul and dared to show me an alternative world of cinema beyond the only one I knew.

What I love and what fascinates me about the cinema of Tom DiCillo is that his themes and narratives speak directly to the heart and to the soul, but not without a distinctly unique cinematic aesthetic and an erudite scrutiny of what it is to be essentially human. DiCillo’s films are entirely approachable, that’s part of their innate charm. There are dual elements at play: the autobiographical exploration and confrontation of his personal history, and the humanist worldview that frames and underscores his narratives. Grand themes explored in a profoundly intimate manner, all staged in a very public arena. These are the works of an artist laying bare and tackling inner demons and questioning it all. Even his non-fiction film about one of the most famous and revered rock bands of the twentieth century feels like a journey into its director’s soul.

Some of the greatest political battles in DiCillo’s films are fought in the family living room. It is psychological warfare with real emotional bloodshed. Unless one is born and raised in complete isolation, removed and sheltered from the stresses and strains that come with being a member of the exclusive club that is family, it is hard to imagine a viewer who could not find something to relate to in a DiCillo film. His work contains an inherent and completely natural empathy for people at their most basic level. One of the things I wanted to explore in this book was DiCillo’s recurrent subtext and continued discourse on family and the trauma that comes from the fractured relationships passed down and shared among fathers and sons, mothers and daughters. In tracking DiCillo’s career from film to film, one is offered a continuity of ideas, themes and motifs; some placed with subtlety, some immediately present.

When I met DiCillo for the first of many discussions for this book, I didn’t know what to expect. With any artist we admire there comes an expectation of them to be representative of the qualities that seduce us with their work. Meeting DiCillo for this book reiterated to me that the humanity in his films was no fluke, nor was I misreading the texts; there really is something deeply relatable in these films beyond their immediate contexts of humour and satire. I spied objects and props from his films throughout his apartment. It was like a museum of my cinematic memories: the guitar from Johnny Suede; the golden apple from Living in Oblivion; the all-seeing eyeball of Double Whammy! Not being familiar with the intense heat of a New York summer and sweating profusely, I perhaps made DiCillo question who he had let into his home when I asked him for ice cold beer at midday, rather than coffee or water, and duly guzzled it down in record time.

On the last night of my visit, at an Upper West Side eaterie, DiCillo gifted me a package containing some rare items of his work. I opened it and the rush of emotion I experienced was intense. All of a sudden this whole venture became real. I was sitting there over food and wine with Tom DiCillo, talking life, art and movies. This project was coming to life before my eyes, and now, several years later, I am very happy to present this book which has been inspired by my immense admiration for DiCillo’s distinct, singular, provocative and, ultimately, joyful work.

DiCillo presents difficult themes and encourages us to contemplate uncomfortable questions about society, ourselves and those closest to us; he just so happens to achieve this within his charmingly absurdist comedic sensibility. A DiCillo film craftily invites us into his whimsical though sharp-edged playground where we are thrilled to peek behind the veil of the most revered entertainment and media industries: film, television, music and fashion. But once past the red carpet, and when the lights go down, we witness a host of neuroses, anxieties, insecurities and utter foolishness. DiCillo’s genius is to make his protagonists – from pop stars to backwoods loners, from supermodels to paparazzi – all densely layered human beings with the same flaws and eccentricities that we all share.

Wayne Byrne: What and when was your introduction to film as a serious medium, as an art form?

Tom DiCillo: My father was in the Marine Corps. We moved every two years, mainly to small towns across America. I didn’t spend a lot of time in big cities. Perhaps if I’d had I might have been more aware of different kinds of film. My early experiences with cinema were actually pretty basic.

More mainstream?

Pretty much. But I remember being very affected by Rebel Without a Cause when I was around thirteen and it stood out for me as a very different film.

What was it about a film like Rebel Without a Cause?

I related to it strongly because it was about this young guy who went to a new school and felt like he didn’t fit in. By that time I’d been to about five different schools. But I didn’t really encounter my first art film until I went to college and saw Fellini’s La Strada. To this moment I can still feel my mind being blown by seeing that movie.

To go back a little bit, at that point my aim was to be a writer. I was into Joyce, Thomas Mann, Kafka…Mark Twain. At the same time I was taking a lot of photographs and printing them in my own darkroom. Then suddenly I encountered this art form that combined it all. Fellini’s film is a monumental achievement in terms of the story, the acting, the human emotion; the philosophical intent. This brute of a man, Zampano, meets a woman, Gelsomina, and she’s the only person in the world who loves him, despite his flaws. Yet he abandons her. That moment at the end of the film where he’s on the beach at night and he looks up at the stars and suddenly realises he is completely alone in the universe is one of the most powerful moments I’ve seen on film.

Then I saw Shoot the Piano Player, The 400 Blows, Breathless, Weekend, The Seven Samurai, Rashomon, Viridiana, The Seventh Seal; all these amazing films which imprinted on me and, for better or worse, formed the base of my cinematic aesthetic. But, it was La Strada that made me say, ‘I’d like to try this.’

I experienced a very similar feeling with Johnny Suede. That’s the film that got me into thinking of cinema as an art form, rather than disposable entertainment. I see some striking parallels between Johnny Suede and La Strada.

Well, I would say La Strada and Midnight Cowboy had the most direct influence on my films. Johnny Suede contains many elements of both.

If you look at the three main characters from those three films: Johnny, Gelsomina and Joe Buck; their respective personalities leave them open to being taken advantage of. They all share this kind of wide-eyed naiveté about the world.

They do. But, Johnny has some of Zampano in him too; that intense self-interest to the degree he can’t see he’s hurting someone who loves him. You can’t survive only on innocence. That struggle fascinates me; you have to be open in life, you have to be willing and trusting; but at the same time what do you do when somebody willfully sets out to crush you? Or you experience a disappointment so severe it cripples you, like Ratso Rizzo?

Growing up in various small towns throughout America at that time, I imagine there weren’t many avenues for you to discover films like La Strada prior to college.

Very few. There was another thing that influenced my passion for film. My father had many rules, like sweeping the crumbs from under the dining room table every night or making us get skinhead haircuts as punishment for bad grades; but the one rule I most hated him for was not allowing us to have a television in the house.

So did your father’s outlawing of this visual medium in turn influence your immersion into the world of literature?

Yes. I would for just sit for days reading, I loved it. I actually think it fostered my ability to think visually. When you read a book it interacts with your mind in such a way that you’re envisioning a private film in a form that is so personal and so strong that no actual filmed representation of it will ever be equal. But even though I loved reading I still was pissed off that I couldn’t watch TV. It affected my interaction with kids at school because they knew all the shows and talked about them all the time. So when my father would be stationed in Japan or Vietnam for thirteen months, the day he walked out of the house my mother would go down to the local electronic store and rent a little black-and-white television.

The illicit thrill of TV?

Yes! It was almost pornographic. We would go on these binges. I swear to God, one time I watched TV for forty-eight hours straight! I had a massive headache, I was cross-eyed. But I was fascinated by everything, even the commercials. And so from a very early age there was an almost erotic, illicit thrill and I still feel that – not that it’s forbidden, but that the pleasure is very intense. It instilled in me an almost mythical respect for the power of cinema, and I think it set a bar for me; something I aspire to in my films.

How did your father react to your budding filmmaking career?

It’s hard to say. Listen, he entered the Marine Corps which meant that he chose a system. This meant he always had a job and always had a paycheck. I think he respects the idea of what I’m trying to do but I don’t think he’s comfortable with how much of it is so nebulous and unpredictable.

How did you end up in New York City?

It was a practical choice. I graduated from a small college in Virginia and applied to two film schools. I went to the school library and looked them up. I don’t even know how I got the idea; this was around the mid-1970s.

At that time the idea of attending film school wasn’t yet a widely acknowledged pursuit…

It barely existed. Scorsese had gone to NYU but the only independent filmmaker I knew at that time was really John Waters. I remember him coming to my college and showing Pink Flamingos on a bed sheet in the parking lot. There was no independent movement, no Filmmaker Magazine, no Sundance Channel. Everything was wide open and formless. But, still I knew filmmaking was something I wanted to do. So I applied to two schools: NYU and this college out in Los Angeles. I had nothing; no money, no film experience and I was amazed that both schools accepted me. NYU took me because they said they liked the photographs I submitted and some short stories that I had written. Since my brother was moving to New York to start a career as a painter I thought, ‘Well, do I want to go all the way out to California by myself? Maybe I’ll go to New York with my brother and go to NYU.’ That’s how I ended up here.

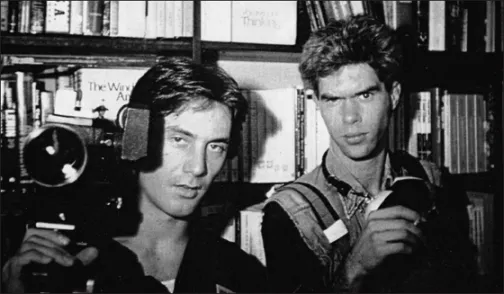

Tom DiCillo (left) and Jim Jarmusch (right) during production of Burroughs: The Movie, 1983

What did film school teach you? Do you feel it was necessary?

For me it was necessary because I knew nothing about filmmaking. But what troubled me the most about the school was their idea of what makes a good film and what makes a bad film. I went there thinking, ‘It’s a school, they’ll let you try things; they won’t force you into a rigid or conventional way of thinking.’ But I was always coming up against this and asking, ‘Wait a second! Why is this not a movie?…Why is that a movie and this isn’t a movie?’ One day they showed Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her and I remember Jim Jarmusch and I – he was in my class – we were the only two who liked the film. I said, ‘This is a very interesting way to tell a story.’ And the rest of the class was incensed. Everyone was yelling, ‘I hate this movie, I hate it; this isn’t a movie!’

Was the resistance so great that you found it a challenge academically?

I did well in my first, second and part of my third year. I won a scholarship grant and a paid position as a teacher’s assistant. But I stumbled with my thesis film. My original idea was intense and very personal but the consensus among the faculty was, ‘No, don’t do this!’ They were so insistent upon it that I started questioning myself. Two weeks before I was to start shooting I wrote another script, still something that interested me but not the film I’d wanted to make.

What was it about that personal film the faculty didn’t want you to pursue?

They just didn’t get it. But the real point is I doubted myself and ended up making a film which did not work. The head of the faculty was this Czech director named Laszlo Benedek whose main claim...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. The Language of Dream: Deciphering DiCillo

- 2. Johnny Suede (1991)

- 3. Living in Oblivion (1995)

- 4. Box of Moonlight (1996)

- 5. The Real Blonde (1997)

- 6. Double Whammy (2001)

- 7. Delirious (2006)

- 8. When You’re Strange: A Film About The Doors (2009)

- 9. Down in Shadowland (2014)

- Notes

- Filmography

- Bibliography

- Index