![]()

PART 1

THE TWO CULTURES MEET IN THE NEW YORK SCHOOL

![]()

INTRODUCTION

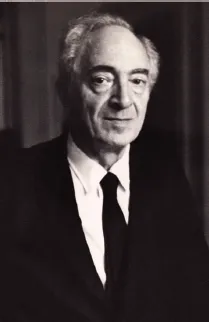

In 1959 C. P. Snow, the molecular physicist who later became a novelist (fig. i.1), declared that Western intellectual life is divided into two cultures: that of the sciences, which are concerned with the physical nature of the universe, and that of the humanities—literature and art—which are concerned with the nature of human experience. Having lived in and experienced both cultures, Snow concluded that this divide came about because neither understood the other’s methodologies or goals. To advance human knowledge and to benefit human society, he argued, scientists and humanists must find ways to bridge the chasm between their two cultures. Snow’s observations, which he delivered in the prestigious Robert Rede Lecture at the University of Cambridge, have since spurred considerable debate over how this could be done (see Snow 1963; Brockman 1995). 1

My purpose in this book is to highlight one way of closing the chasm by focusing on a common point at which the two cultures can meet and influence each other—in modern brain science and in modern art. Both brain science and abstract art address, in direct and compelling fashion, questions and goals that are central to humanistic thought. In this pursuit they share, to a surprising degree, common methodologies.

While the humanistic concerns of artists are well known, I illustrate that brain science also seeks to answer the deepest problems of human existence, using as an example the study of learning and memory. Memory provides the foundation for our understanding of the world and for our sense of personal identity; we are who we are as individuals in large part because of what we learn and what we remember. Understanding the cellular and molecular basis of memory is a step toward understanding the nature of the self. In addition, studies of learning and memory reveal that our brain has evolved highly specialized mechanisms for learning, for remembering what we have learned, and for drawing on those memories—our experience—as we interact with the world. Those same mechanisms are key to our response to a work of art.

i.1 C. P. Snow (1905–1980)

Whereas the artistic process is often portrayed as the pure expression of human imagination, I show that abstract artists often achieve their goals by employing methodologies similar to those used by scientists. The Abstract Expressionists of the New York School of the 1940s and 1950s provide an example of a group that probed the limits of visual experience and extended the very definition of visual art. (For earlier attempts to bridge the two cultures, see E.O. Wilson 1977; Shlain 1993; Brockman 1995; Ramachandran 2011.)

Until the twentieth century, Western art had traditionally portrayed the world in a three-dimensional perspective, using recognizable images in a familiar way. Abstract art broke with that tradition to show us the world in a completely unfamiliar way, exploring the relationship of shapes, spaces, and colors to one another. This new way of representing the world profoundly challenged our expectations of art.

To accomplish their goal, the painters of the New York School often took an investigative, experimental approach to their work. They explored the nature of visual representation by reducing images to their essential elements of form, line, color, or light. I examine the similarities between their approach and the reductionism that scientists use by focusing on these artists as they move from figurative to abstract art—in particular, the work of the early reductionist painter Piet Mondrian and the New York painters Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Morris Louis.

Reductionism, taken from the Latin word reducere, “to lead back,” does not necessarily imply analysis on a more limited scale. Scientific reductionism often seeks to explain a complex phenomenon by examining one of its components on a more elementary, mechanistic level. Understanding discrete levels of meaning then paves the way for exploration of broader questions—how these levels are organized and integrated to orchestrate a higher function. Thus scientific reductionism can be applied to the perception of a single line, a complex scene, or a work of art that evokes powerful feelings. It might be able to explain how a few expert brushstrokes can create a portrait of an individual that is far more compelling than a person in the flesh, or why a particular combination of colors can evoke a sense of serenity, anxiety, or exaltation.

Artists often use reductionism to serve a different purpose. By reducing figuration, artists enable us to perceive an essential component of a work in isolation, be it form, line, color, or light. The isolated component stimulates aspects of our imagination in ways that a complex image might not. We perceive unexpected relationships in the work, as well as, perhaps, new connections between art and our perception of the world and new connections between the work of art and our life experiences as recalled in memory. A reductionist approach even has the capacity to bring forth in the beholder a spiritual response to the art.

My central premise is that although the reductionist approaches of scientists and artists are not identical in their aims—scientists use reductionism to solve a complex problem and artists use it to elicit a new perceptual and emotional response in the beholder—they are analogous. For example, as I discuss in chapter 5, early in his career J.M.W. Turner painted a struggle at sea between a ship heading for a distant harbor and the natural elements: the storm clouds and rain bearing down on the ship. Years later, Turner recast this struggle, reducing the ship and the storm to their most elemental forms. His approach allowed the viewer’s creativity to fill in details, thereby conveying even more powerfully the contest between the rolling ship and the forces of nature. Thus, while Turner explores the boundaries of our visual perception, he does so to engage us more fully with his art, not to explain the mechanisms underlying visual perception.

Reductionism is not the only fruitful approach to biology, or even to brain science. Important, often critical insights are gained by combining approaches, as is evident in the advances made in brain science through computational and theoretical analysis. Indeed, a major step forward in the study of the brain was the scientific synthesis that occurred in the 1970s, when psychology, the science of mind, merged with neuroscience, the science of the brain. The result of this unification was a new, biological science of mind that enables scientists to address a range of questions about ourselves: How do we perceive, learn, and remember? What is the nature of emotion, empathy, and consciousness? This new science of mind promises not only a deeper understanding of what makes us who we are but also to make possible meaningful dialogues between brain science and other areas of knowledge, such as art.

Science attempts to move us toward greater objectivity, a more accurate description of the nature of things. By examining the perception of art as an interpretation of sensory experience, scientific analysis can, in principle, describe how the brain perceives and responds to a work of art, and give us insights into how this experience transcends our everyday perception of the world around us. The new, biological science of mind aspires to a deeper understanding of ourselves by creating a bridge from brain science to art, as well as to other areas of knowledge. If successful, this endeavor will help us understand better how we respond to, and perhaps even create, works of art.

Some scholars are concerned that focusing on reductionist approaches used by artists will diminish our fascination with art and trivialize our perception of its deeper truths. I argue to the contrary: appreciating the reductionist methods used by artists in no way diminishes the richness or complexity of our response to art. In fact, the artists I consider in this book have used just such an approach to explore and illuminate the foundations of artistic creation.

As Henri Matisse observed: “We are closer to attaining cheerful serenity by simplifying thoughts and figures. Simplifying the idea to achieve an expression of joy. That is our only deed.”

![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE EMERGENCE OF AN ABSTRACT SCHOOL OF ART IN NEW YORK

In the years following the end of World War II, a number of artists began to wonder how art could still be meaningful in the aftermath of such a tragic period in world history, a period that encompassed the horrors of the Holocaust, the enormous loss of life on the battlefield, and the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. What visual language could possibly describe a world so transformed? Many artists in the United States felt compelled to create art that was unmistakably different from what had come before. One of the great artists of this period, Barnett Newman, wrote about his response and that of his fellow artists: “We are freeing ourselves of the impediments of memory, association, nostalgia, legend, myth, or what have you, that have been devices of Western European painting.”

In their attempt to abandon European influences, the American artists created Abstract Expressionism, the first American art movement to gain international acclaim. In moving from figurative art to abstract art, the New York School of painters—notably, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko—and their colleague Morris Louis were taking a reductionist approach. That is, rather than depicting an object or image in all of its richness, they often deconstructed it, focusing on one or, at most, a few components and finding richness by exploring those components in a new way.

These New York artists of the 1940s and 1950s were surrounded by an exciting and influential group of intellectuals and owners of art galleries. Many European psychoanalysts, scientists, physicians, composers, and musicians—as well as the artists Piet Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, and Max Ernst—had come to New York in the late 1930s and early 1940s to escape the war in Europe. They arrived soon after the opening of the Museum of Modern Art in 1929 and the Guggenheim Museum in 1939 and the rise of affluent, farsighted gallery owners such as Peggy Guggenheim and Betty Parsons. These museums, galleries, and émigré artists actively promoted the New York School as the first avant-garde school of painting that was authentically and emphatically American—in its spirit, its expansive scale, and its expression of individual freedom.

As a result, the center of modernist art shifted from Paris to New York. Thus, while Paris had been the New Jerusalem of the art world in 1900, New York became the New Jerusalem in the late 1940s. Mondrian, a pioneer reductionist who escaped from Europe when World War II broke out, described this shift in a virtual manifesto for abstraction in art: “In the metropolis, beauty is expressed in more mathematical terms; that is why it is the place . . . from which the New Style must emerge” (Spies 2011, 6:360). Roger Lipsey, a student of modern art, calls this period in the 1940s the “American epiphany,” a revelation of the sacred qualities inherent in art. In fact, de Kooning, Pollock, Rothko, and Louis openly referred to the spiritual nature of their art.

The impact of the modernist movement was enhanced by the presence in New York of a contemporaneous school of art critics, particularly Harold Rosenberg of The New Yorker and Clement Greenberg of the Partisan Review and The Nation. These critics responded to the new art by developing a novel way of thinking about it. They focused almost exclusively on form and gesture, finding in the space, color, and structure of a painting the basis for a complex and satisfying critical perspective (Lipsey 1988, 298). Their enthusiasm for the New York School of painting was shared by Meyer Schapiro, professor of art history at Columbia University. He was the most important art historian of his time and the first art historian to appreciate the importance of the new American approach to art. As Barnett Newman pointed out, Schapiro was the first major scholar to defend American painting abroad.

1.1 Harold Rosenberg (1906–1978)

Rosenberg (fig. 1.1) rose to prominence in 1952 with the publication of his essay “The American Action Painters” in Art News. He saw American art as moving along new lines. Painters, he wrote, were no longer concerned with the technical aspect of art, but were focused on treating the canvas as an “arena in which to act. . . . What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.” According to Rosenberg, the formal qualities of an artwork were not important. What was important was the creative act.

As a result of this highly influential essay, which offered the first coherent overview of “gestural abstraction,” Rosenberg emerged as one of the important art critics of the early 1950s. Although he did not single out any individual artist, his analysis lent itself particularly well to de Kooning and to Pollock; it applied much less well to the color-field painters, such as Rothko, Louis, and Kenneth Noland.

1.2 Clement Greenberg (1909–1994)

It was Greenberg (fig. 1.2), however, who ultimately formulated the aspirations of the New York School. He recognized and advocated not just for de Kooning and Pollock, whom he saw early on as moving abstraction to a dominant position in avant-garde art, but also for the color-field painters, who focused on combining colors to elicit strong emotional and perceptual responses in the beholder. Greenberg’s almost single-handed defense of the new directions in what he termed “American style painting,” at a time when modernism was almost categorically defined as the School of Paris, gave him unmatched credibility (Danto 2001).

Unlike Rosenberg, Greenberg did not see Pollock, Rothko, and the color-field painters of the New York School as breaking with historical tradition. Instead, he recognized in their work the culmination of an artistic tradition that had begun with Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley, then evolved through Paul Cézanne into analytic Cubism. In this progression, painting became increasingly focused on what Cézanne saw as its essential nature: the making of marks on a flat surface (Greenberg 1961). In the late 1950s and the 1960s, particularly in his 1964 essay “After Abstract Expressionism,” Greenberg placed progressively more emphasis on the color-field painters, whom he saw as developing an even more radical approach to conventional easel painting.

1.3 Meyer Schapiro (1904–1996)

Schapiro (fig. 1.3), unlike Greenberg and Rosenberg, did not identify with a particular school or painter, but brought his rich knowledge of art history and theory to bear on the contemporary art scene. As a result, he exerted a dramatic influence on contempo...