![]()

[1]

SCIENCE

How It Works

Science. Everybody says they are for it. So why the firestorm of argument about the science of climate change? It’s an interesting question. With a disturbing answer. For all the complexity of detail in science, the process is actually fairly straightforward.

Science is unique among human endeavors in the “self-correcting” machinery (to quote the famous Carl Sagan)1 by which it is governed. That machinery ensures that science continues on a path toward an increasingly better understanding of the natural world despite the occasional wrong turns, dead ends, and missteps. The machinery consists of the critical checks that exist in the form of peer review and professional challenges, with the overriding maxim—again attributed to Sagan2—that extraordinary claims especially require extraordinary evidence. Good-faith skepticism—that is, skepticism that attempts to hold science to the highest possible standard through independent scrutiny and questioning of every minute detail—is not only a good thing in science but, in fact, essential. It is the lubricant that ensures that the self-correcting machinery continues to function.

Unfortunately, the term skeptic has been hijacked, especially in the climate change debate, to mean something entirely different. It is used as a way to dodge evidence that one simply doesn’t like. That, however, is not skepticism but rather contrarianism or denialism, the wholesale rejection of validated, widely accepted scientific principles on the basis of opinion, ideology, financial interest, self-interest, or all these things together.

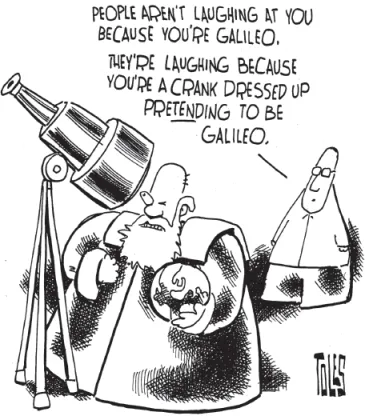

We must distinguish true skepticism—a noble attribute found in all good science and all good scientists—from the pseudoskepticism practiced by armchair science critics who misguidedly fancy themselves modern-day Galileos. As Carl Sagan also once said, “The fact that some geniuses were laughed at does not imply that all who are laughed at are geniuses. They laughed at Columbus, they laughed at Fulton, they laughed at the Wright Brothers. But they also laughed at Bozo the Clown.”3 For every Galileo, there are many thousands of Bozo the Clowns. When it comes to the fractious debate over policy-relevant areas of science, the Bozos are too often the ones with the megaphones.

Skepticism

True scientific skepticism takes many forms. Skepticism takes place in the give-and-take at scientific meetings, where scientists present their findings and then address questions, criticisms, and challenges from their colleagues in the audience. It takes place in the form of peer review: Scientists write up their findings and submit them to journals. The journals select several other scientists with expertise in the field to critically evaluate the submission. If they find flaws in the data, the underlying assumptions, the experimental design, or the logic, the authors must revise and resubmit. This process might be repeated a number of times for a single article. In the end, the article is published if and only if the editor determines that the authors have satisfactorily addressed any concerns or critiques raised during the review process and that the manuscript represents a positive contribution to the existing scientific literature.

The quality-control process of peer review isn’t perfect, of course, and flawed work inevitably does get published. Certainly, no single scientific article ever defines the collective body of knowledge. And so there is even peer review of peer review in the form of multiauthored scientific assessments, like those by the National Academy of Sciences, that evaluate the collective evidence in the peer-reviewed literature on a particular topic and summarize the state of knowledge on the topic. These assessments, too, are peer reviewed for accuracy, objectivity, and thoroughness.

The fact of the matter, however, is that there is a weakness in the scientific system that can be exploited. The weakness is in the public understanding of science, which turns out to be crucial for translating science into public policy. Deliberate confusion can be sown under a false pretext of “skepticism.” And the scientific process is continually under assault by bad-faith doubt mongers.

There is, for example, the whole duplicitous game of assigning motives. Critics sometimes seek to cast suspicion on the scientific enterprise by suggesting that it is compromised by a conspiracy of ulterior-motive-driven individuals. “The scientists are in it for the money,” they say, seeking to “get rich off of government grant money.” Ironically, there is no small amount of projection here. These accusations, after all, are typically made by talking heads who get paid hefty sums by industry front groups to peddle disinformation to the public and to attack the scientists.4 But what about the substance of the accusation? Do climate scientists, for example, seek to reinforce the dominant narrative that climate change is real and caused by humans to generate concern from the public and policy makers just so they can guarantee the ongoing availability of government grant support for their work?

To understand just how absurd that premise is, we have to understand something about how science really works. In science, you don’t make a name for yourself by simply reinforcing the dominant narrative. You don’t get articles published in the premier journals Nature and Science by simply showing that others were right. The way you establish a name for yourself in the world of science is by demonstrating something new or surprising, by contradicting conventional wisdom. A record of novel, groundbreaking work is what gets you tenure, what helps bring in research grants, what leads to salary increases from your institution.

Any scientist who could soundly demonstrate that Earth is not warming would become an instant science celebrity. A scientist who could definitively explain the warming of Earth by natural rather than human causes would have prominent articles published in Nature and Science. He or she would appear on the network news and make the cover of Scientific American. Such an individual would be tenured, promoted, likely elected to the National Academy of Sciences. The scientist would go down in history as one of the great paradigm breakers of all time, part of the exclusive club that includes Galileo, Newton, Darwin, Einstein, and Wegener (of plate tectonics fame). Such a scientist would, in short, achieve both fame and fortune.

So the incentives for a scientist would appear to be rather the opposite of what the critics claim. But let us not forget that in science the more extraordinary the claim, the more extraordinary the evidence must be. If you are a scientist who publishes a bold new claim, you better be prepared to defend it scientifically, for there will be a proverbial target on your back. Other scientists will be gunning for you. Discrediting your famous new finding might be just the ticket to their own fame and glory. Remember “cold fusion”—the controversial claim by a pair of chemists in the late 1980s that it was possible to generate fusion energy at room temperature using little more than tap water and a couple of electrodes? The American Physical Society devoted a whole session at its annual meeting to debunking it. A group of Caltech physicists were celebrated by the scientific community and gained quite a bit of public exposure for discrediting the claim. But they, in turn, had to prove their case. They had to present compelling evidence that the “cold fusion” claim was wrong, which they did.5 That’s the way it works.

The Hockey Stick

We would be remiss in this context not to recount the tale of the hockey stick. In the late 1990s, one of the two authors of this book (Michael Mann) published the now-famous “hockey stick curve” depicting temperature trends over the past millennium. The curve demonstrated the unprecedented nature of modern global warming. It became a symbol in the climate change debate and thus a potent object of attack to some.6 Given the iconic status of the hockey stick curve, there was a huge potential reward in terms of scientific notoriety for any scientist who could demonstrate it wrong. Many have indeed tried.

Dozens of scientific groups have performed their own studies, using different data and different methods and coming to their own independent conclusions. Challenges to the hockey stick curve have been published in the leading scientific journals, such as Nature and Science. Some of these challenges helped launch the careers of ambitious young scientists. Yet a decade and a half later, a veritable hockey league of studies confirms the basic hockey stick conclusion.7 The most comprehensive study to date has yielded a curve that is virtually indistinguishable from the original hockey stick curve.8 The basic finding has stood the test of time. Scientists have now largely moved on, seeking answers to other related questions (for example, What natural factors primarily drove prehistoric temperature changes?). That’s how science works. What once lay at the scientific forefront—the speculative boundary of scientific understanding—is slowly absorbed into the corpus of scientific knowledge. But if—and only if—it stands up to repeated challenge. The boundary of scientific knowledge expands, and science moves on, exploring new frontiers. If the original hockey stick curve had indeed been wrong, we would know by now. If assertions of global warming were wrong, we would know by now. If global warming were not caused by humans, we would know by now. The incentive structure in science is such that establishing any of those propositions—were it possible—would be irresistible to some aspiring young scientist looking to establish his or her name.

That is not at all to say that efforts to discredit the hockey stick curve or assertions of global warming or the human cause of global warming have ceased. Quite the contrary. Although the scientific community may consider these points to be settled fact and may have moved on, there are others who have not. Powerful vested interests that consider such findings rather inconvenient fight on. Just as the tobacco industry found medical research revealing the damaging health impacts of cigarette smoking to be a threat to its interests and so recruited contrarian scientists, think tanks, and lobbying firms to participate in a massive public disinformation campaign aimed at undermining the public’s faith in the scientific evidence,9 and just as the chemical industry has continued to seek to discredit science demonstrating negative health and environmental impacts of their products, fossil fuel interests have continued to spend tens of millions of dollars in an ongoing public-relations campaign to discredit the science of human-caused climate change, including the hockey stick curve itself.10 These attacks are part of what has been called a “war on science,”11 a war waged by special interests seeking to avoid oversight and regulation in the face of compelling scientific evidence that exposes the risks created by their products, actions, and services.

The Bizarro World

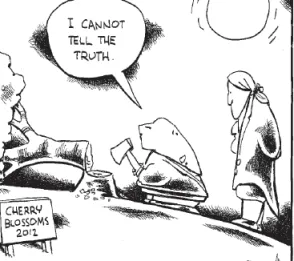

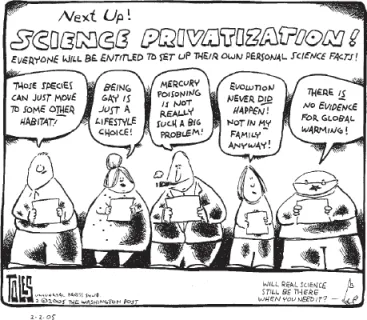

The late senator Daniel P. Moynihan (D-N.Y.) once famously quipped, “You’re entitled to your own opinions but not your own facts.” Unfortunately, in today’s world many do feel entitled to their own facts—particularly when those alternative “facts” support an agenda. If you read the Wall Street Journal editorial page or tune into Fox News, you find yourself in a Bizarro world where up is down, left is right, and black is white. Ozone depletion is a myth. Pollution? Shmolution! And evolution? Just a theory. Acid rain is caused by trees. And global warming? Don’t even get us started on global warming!

A growing number of American citizens find themselves trapped within the Bizarro world’s bubble of misinformation. Gone are the days of Walter Cronkite when “that’s the way it was,” when we could agree on the facts and politely agree to disagree on their implications. Nowadays, many of us choose to access only those sources of information (networks, websites, newspapers, radio shows) that simply reinforce our preconceptions. If you’re a fervent climate change denier, there is a good chance that you (1) aren’t reading this book anyway, (2) don’t read Tom’s editorial cartoons in the Washington Post or Mike’s commentaries and interviews, and (3) get your information about climate change from conservative media outlets committed to perpetuating the notion that climate change is a myth, a vast conspiracy by thousands of scientists around the world perpetrating a massive hoax to create a new socialist world order.

If that is your viewpoint, it probably doesn’t matter to you that the world’s scientists have reached an overwhelming consensus that climate change is (1) real, (2) caused by us, and (3) already a problem. It probably doesn’t matter that the National Academy of Sciences, founded by (Republican) President Abraham Lincoln, has stated this to be the case, as have the scientific academies of all the major industrial nations.12 It probably doesn’t matter that every scientific society in the United States to weigh in on the matter has done so as well.13 From your perspective, that’s all just evidence that the scientific conspiracy must run even wider and deeper. It is this sort of epistemic closure that makes it increasingly difficult to reach hardened climate change deniers.

Science is litigated through the formulation and testing of hypotheses, the analysis of hard data, and an examination of the facts, not by television debates between talking heads with opposing viewpoints. Yet our mass media too often frame climate change precisely that way. Who do you imagine benefits from that framing?

Doubt Is Their Product

When it comes to the public battle over policy-relevant science, special interests have long recognized that they enjoy the advantage of the prosecution in the court of public opinion. Their internal research, focus groups, and polling have revealed that they need generate only sufficient uncertainty about the scientific evidence in the public mind-set to ensure an agenda of inaction. “Doubt is our product” read one internal tobacco industry memo.14

It is unsurprising that right-wing media outlets serve as mouthpieces for this agenda. But what is more troubling is that the mainstream media have often played the role of unwitting accomplices. By perpetuating the notion that there are two equal “sides” when it comes to objective matters of fact such as evolution and climate change, mainstream-media outlets have reinforced the perception that there is legitimate doubt about these matters. Comedian John Oliver had it precisely right when he brought ninety-seven scientists out onto the studio floor (incl...