![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

1. In Search of the Wild Horse

The Daoist Horse Taming Pictures are a series of twelve illustrated poems, ten of which are equine-centered and two of which are non-equine-centered. They use the analogy of horse training, or “taming the wild horse,” to discuss Daoist contemplative practice, specifically the necessity of reining in sensory engagement and harnessing chaotic psychological patterns through dedicated and prolonged meditation. Here the “wild” or “untamed horse” symbolizes ordinary mind and habituated consciousness, which are characterized by high degrees of sensory engagement, emotional volatility, and intellectual reactivity. The poems and associated verse commentary were most likely written by Gao Daokuan, a Daoist monk of the Complete Perfection monastic order. In this chapter, I discuss Gao’s life story, including his Daoist lineage, and the key characteristics of Complete Perfection monasticism. I also examine the training regimen that informs and is expressed in the illustrated poems, with particular attention to meditation methods. Such considerations provide the necessary foundation for engaging the Horse Taming Pictures as a map of Daoist contemplative practice and contemplative experience, a description of stages on the Daoist contemplative path.

The Master of Complete Illumination

With respect to authorship, the Daoist Horse Taming Pictures are attributed to Yuanming laoren (Venerable Complete Illumination). As Yuanming is the Daoist religious name of Gao Daokuan (1195–1277),1 the text was most likely composed by him. This identification is substantiated by the content of the associated text, as it contains major Quanzhen (Ch’üan-chen; Complete Perfection) themes, concerns, and technical terms.2 While the text is not mentioned in Gao’s hagiographies, the same is true for most of the entries in the thirteenth-century Zhongnan shan Zuting xianzhen neizhuan (Esoteric Biographies of Immortals and Perfected of the Ancestral Hall of the Zhongnan Mountains; DZ 955; ZH 1489; abbrev. Esoteric Biographies from the Zhongnan Mountains).3 That is, unlike other Complete Perfection hagiographies, which list known works authored by the given adherent, the Esoteric Biographies from the Zhongnan Mountains does not (see Komjathy 2007, 2013a). In some respects, Gao himself resembles a wild horse galloping through Daoist history; he has largely disappeared into the landscape and is now difficult to catch a glimpse of.

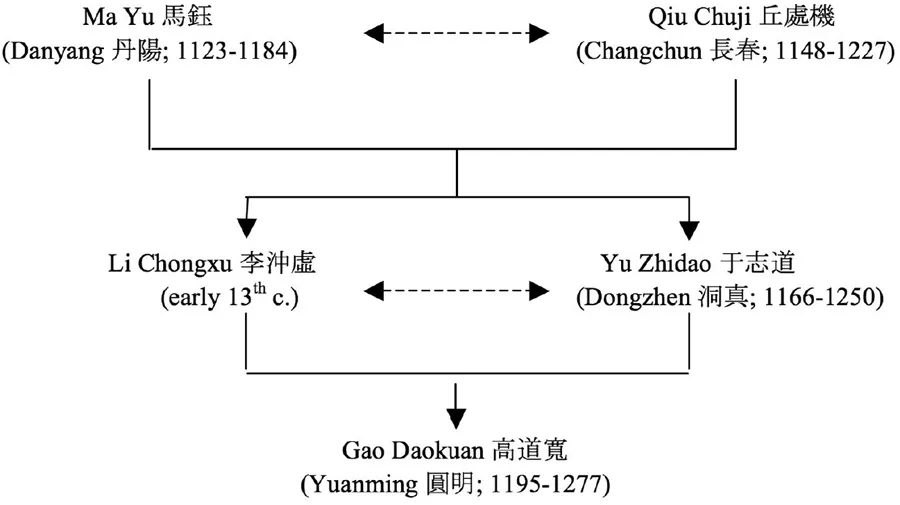

Gao Daokuan was a third-generation member of the Complete Perfection Daoist movement and thus a Complete Perfection monk in the monastic order. As discussed in more detail below, he was a disciple of the somewhat obscure Li Chongxu (early thirteenth c.) and then of Yu Zhidao (1166–1250), both of whom were second-generation Complete Perfection adherents.

According to the Esoteric Biographies from the Zhongnan Mountains, Gao Daokuan was born in 1195 in Huairen county in Yingzhou, which is near Datong and Shouzhou in present-day Shanxi province (central China). He descended from the Hao clan, possibly a prominent Shanxi aristocratic line. He was an only child, and he received what appears to have been a traditional literati education. When Gao was around fourteen years of age, his family moved to Chang’an (present-day Xi’an, Shaanxi), where his father worked as an official scribe (daobi shi), which was a low-level sub-official position in the imperial bureaucracy (Hucker 1985, 6320). Both his father and mother died when Gao was in his twenties. While performing funeral and mourning rites, Gao is said to have had a mystical experience:

One evening while sitting in the family hall, in the middle of the night he suddenly beheld a radiant illumination like dawn. As he looked east and west, the Gates of Heaven (tianmen) opened wide. Between red clouds and green vapors, he successively saw beautiful forests, rare trees, precious halls, and amazing terraces. After a little while, the sky closed again. From that point forward, [Master Gao] only had a heart-mind for studying the Dao (xuedao). (Esoteric Biographies from the Zhongnan Mountains [DZ 955], 3.29a)

In other words, Gao apparently gained a vision of the Daoist celestial and immortal realms.

In 1221, at the age of twenty-six, Gao decided to become a Daoist renunciant and monastic (chujia, lit., leave the family). Significantly, at this point in Complete Perfection history, which I have previously labeled the “expansive phase” (Komjathy 2007), Qiu Chuji (Changchun [Perpetual Spring], 1148–1227),4 the last surviving first-generation adherent, Third Patriarch, and national leader of the monastic order, and his disciples were in the process of establishing, inhabiting, and maintaining a vast network of Daoist temples and monasteries in northern China. Qiu, now seventy-three with only six years remaining in his life, was working with second-generation luminaries such as Li Zhichang (Zhenchang [Perfected Constancy]; 1193–1256), Song Defang (Piyun [Wrapped-in-Clouds]; 1183–1247), Wang Zhijin (Qiyun [Perched-in-Clouds]; 1178–1263), and Yin Zhiping (Qinghe [Clear Harmony]; 1169–1251), who would succeed Qiu as Complete Perfection Patriarch. This was also the time (1220–1223) when Qiu made his famous “westward journey” to meet the Mongol leader Chinggis Qan (Genghis Khan; ca. 1162–1227; r. 1206–1227) in the Hindu Kush (present-day Afghanistan).5

Gao Daokuan entered the Complete Perfection monastic order under an obscure Daoist master An of Penglai an (Hermitage of Penglai),6 which may have been located in or near Chang’an. Gao trained under Master An for about three years. Then, in 1224, at the age of twenty-nine, he moved to Bianliang (present-day Kaifeng, Henan), where Wang Zhe (Chongyang [Redoubled Yang]; 1113–1170), the movement’s founder, had died. There, Gao became a disciple of Li Chongxu of Danyang guan (Monastery of Danyang), a Complete Perfection Daoist temple named in honor of Ma Yu (Danyang [Elixir Yang]; 1123–1184). Li Chongxu’s identity remains obscure. He may be Li Chongdao (Qingxu [Clear Emptiness]; fl. 1170–1230), a second-generation Complete Perfection adherent with connections to Yu Zhidao. Li Chongdao was a disciple first of Ma Yu and then of Qiu Chuji, both of whom were senior first-generation disciples of the founder.7

In 1226, under the direction of the Jin emperor Aizong (1198–1234; r. 1224–1234), the prominent Complete Perfection Daoist Yu Zhidao (Dongzhen [Cavernous Perfection]; 1166–1250) moved to Bianliang, where he became abbot of Taiyi gong (Palace of Great Unity). Like Li Chongdao, Yu Zhidao was first a disciple of Ma Yu and then of Qiu Chuji.8 Li Chongxu encouraged his disciple Gao Daokuan to train under Yu Zhidao, which Gao did until 1233. The same year, the Mongols besieged Kaifeng, eventually defeating the Jurchen forces and capturing the capital city.9

Lineage, training, and transmission are centrally important in the Daoist tradition in general and in Complete Perfection Daoism in particular.10 Specifically, Daoists tend to consider their spiritual genealogy or lines of descent through family metaphors, such as by referring to one’s primary teacher as “master-father” (shifu) and one’s teacher’s teacher as “master-grandfather” (shiye). Gao’s location in the early Complete Perfection monastic order is significant because he trained with two teachers, Li and Yu, who were direct disciples of Ma and Qiu. Ma Yu and Qiu Chuji were members of the so-called Seven Perfected (qizhen)—that is, senior first-generation Shandong disciples of Wang Zhe, the founder of Complete Perfection. There is a direct line of transmission, which included formal monastic ordination in Gao’s case (fig. 1.1).

In addition to living in Bianliang (1224–1233), Gao resided in Longyang guan (Monastery of Dragon Radiance), located in the area above Yanjing (present-day Beijing), between 1233 and 1238. Following his semi-seclusion there, Gao traveled to Yanjing at the request of Yu Zhidao. Then, in 1240, at the age of forty-five, Gao Daokuan moved to Chongyang gong (Palace of Chongyang [Redoubled Yang]) in Liujiang (present-day Huxian), Shaanxi. Referred to as Zuting (Ancestral Hall), this was the location of Wang Zhe’s early hermitage and then of his grave and shrine. As such, it was perhaps the key Complete Perfection devotional and pilgrimage site during this period of Daoist history. Gao lived in or near this Daoist sacred site for the remainder of his life, serving as the temple manager of Yuxian gong (Palace for Meeting Immortals) in Ganhe (1248–1252) and then as Daoist registrar for Jingzhao (1252–1261). During this time, he collaborated with and was honored by the national leaders of Complete Perfection: Li Zhichang (Zhenchang [Perfect Constancy]; 1193–1256), Zhang Zhijing (Chengming [Sincere Illumination]; 1220–1270), and Wang Zhitan (Chunhe [Pure Harmony]; 1200–1272). In addition to teaching his disciples and conducting rituals, Gao was involved in major renovations and additions to the Palace of Redoubled Yang.

Figure 1.1. Daoist lineage affiliation of gao daokuan

Gao Daokuan died in 1277, only two years before the final Mongol conquest of the whole of China and the formal establishment of their Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). According to his hagiography, “On the twenty-fourth day, he suspended his eating and sat with a dignified manner for the entire day. His conversation was just as it had been in earlier times, with him providing instructions about advancing in the Dao to his disciples. On the following day, he suddenly transformed [died] in the quiet room where he was staying. He had enjoyed eighty-three springs and autumns” (Esoteric Biographies from the Zhongnan Mountains [DZ 955], 3.32a).

The Way of Complete Perfection

Quanzhen began as a small ascetic and eremitic Daoist community around 1163.11 The two earliest Complete Perfection communities were based in Shaanxi and Shandong and emphasized intensive, dedicated and sustained religious training. Early Complete Perfection centered on ascetic discipline, meditative praxis, and mystical experience. The early community became the foundation for a regional and national movement, eventually developing into a national monastic order. As mentioned, the order’s establishment occurred under the direction of Qiu Chuji, the last surviving senior first-generation disciple of the founder and third Complete Perfection Patriarch, and his own senior disciples. The life and times of Gao Daokuan correspond to the “organized” and “expansive” periods of Complete Perfection history, specifically the institutionalization and development of Complete Perfection as a monastic order. This occurred from the early to late thirteenth century, corresponding to the latter part of the Song–Jin period and the early Yuan dynasty, which may have particular relevance for thinking about and with horses (see ch. 2 below).

Early medieval Complete Perfection monasticism encompassed a vast network of hermitages, temples, and monasteries throughout northern China, with Shaanxi and Shandong remaining key centers. Gao resided in a variety of Daoist monasteries: the Hermitage of Penglai, possibly in Chang’an, Shaanxi; the Monastery of Elixir Yang and Palace of Great Unity, both in Bianliang, Henan; the Monastery of Dragon Radiance, near Beijing; and the Palace of Redoubled Yang, in Liujiang, Shaanxi. These dimensions of Gao’s life and his sociohistorical location invite inquiry into the defining characteristics of late medieval Complete Perfection monasticism, specifically the order’s training regimens. These inform and are expressed in Gao’s Horse Taming Pictures.

By this time, larger Complete Perfection monasteries, at least from an idealized perspective, contained a central hall with a central altar, a meditation hall, refectory (dining hall), sleeping quarters, and so forth. The central altar was usually dedicated to the Sanqing (Three Purities), three high Daoist “gods” with various symbolic associations and theological interpretations (see Komjathy 2013b). Complete Perfection devotional and ritual activity also increasingly centered on the so-called Five Patr...