![]()

1

HISTORY AND HERSTORY IN THE 1970S AND 1980s3

It is a nasty, disgusting picture that should be banned forever from the face of the earth. Those who enjoy watching the rape scenes must be potential rapists and those who enjoy the revenge scenes must be sadists…. This is the most anti-feminine movie ever made…It is the most vilified picture in cinema’s history.

– Meir Zarchi detailing critics’ comments of ISOYG (2010b)

To fully appreciate the significant impact ISOYG had on audiences and critics on its first release, i.e. its condemnation as one of the most misogynistic sexually violent films ever made, one first needs to delve into the highly-charged gender powder keg that was 1970s America. The feminist movement had already begun to make headway in the decade before with landmarks such as the creation of the Presidential Commission on the Status of Women in 1961 (set up to advise the Commander-in-Chief on issues regarding women’s equality in education), the establishment of the National Organisation for Women by activist Betty Friedan in 1966 and the protesting of the 1968 Miss America pageant. In 1972, the year that Helen Reddy’s number one single ‘I Am Woman (Hear Me Roar)’ became a key paean of the US feminist movement, the Equal Rights Amendment to the US Constitution, outlawing sexual discrimination, was passed. Throughout the 1970s, feminism made huge changes to US society at work and in the home. In the former, record numbers of anti-discrimination and equal opportunity policies provided women access to hitherto denied professions; in the latter, many US states passed new ‘no-fault’ divorce laws, making the process simpler and splitting the assets more evenly. Birth control was relaxed, marriage was no longer an aspiration and many women chose to experiment with a single lifestyle. Prominent feminists such as Frieden and Gloria Steinem held conferences, created organisations and penned literature aimed at empowering women. All across the US, women were becoming more confident, self-reliant and proud of their capabilities; a January 1980 Cosmopolitan survey of 106,000 women revealed that single women not only made more money than their married counterparts, they were also healthier and having more sex.

It is unsurprising then, with men finding themselves emasculated and their place in society shifting, that a backlash occurred – one ‘returns every time women begin to make some headway towards equality’ (Faludi 1993: 66). And it is during these periods of backlash, Susan Faludi argues, that ‘images of the restrained woman line the walls of the popular culture’s gallery. We see her silenced, infantilised, immobilised or, the ultimate restraining order, killed’ (1993: 93). After World War II, which had witnessed women enter the workforce in previously unforeseen numbers, this misogyny was reflected on the silver screen in the form of ‘women’s films’ which tried ‘by ridicule, intimidation, or persuasion, to get women out of the office’ (Haskell 1987: 221).4 As women became more of a serious threat to men in terms of earning power, the films of the 1940s and 1950s embodied patriarchal fears. As Anne (Irene Dunne) tells Jonathan (Charles Coburn) in Together Again (1944), ‘women can live perfectly well without men. But you’re terrified of the idea that they can.’ The threat of enervation was evident in such science fiction titles as The Incredible Shrinking Man (1958) and Attack of the 50-Foot Woman (1958).

The celluloid creation of female vampires in Dracula (1931), Mark of the Vampire (1935) and Dracula’s Daughter (1936) can similarly be regarded as ‘a projection of both male fantasy and fear; a response to modern redefinitions of “the feminine” and to the social and sexual freedoms which were increasingly being demanded by women’ (Rhodes and Springer 1996: 25). Followed by the femme fatale of the 1930s and 1940s, these were representations of women that needed to be destroyed; ‘this drive to punish or eradicate these dangerously active and sexual figures has often been interpreted as a sign of the anti-feminist tendencies of the texts in which they appear’ (Read 2000: 180). It is no surprise that the correlation between the image of woman-as-vampire and the ‘new Woman’ witnessed after World War I produced the term ‘vamp’, used to describe women who were ‘both highly beautiful and highly dangerous…who figuratively sucked the life out of the men that fell at their feet…[and who] became an early twentieth-century embodiment of women’s sexual freedom and, by extension, a symbol of women’s growing demands for social and sexual equality with men’ (Rhodes and Springer 1996: 31, 28). Barbara Creed argues that the re-emergence of the female nosferatu in the 1970s – with an even stronger sexual appetite – is directly connected to the advance of second-wave feminism and public fears about a more threatening expression of female sexuality (1993: 59). A lot of the horror titles of this era succinctly summed up these sexual overtones – The Vampire Lovers (1970), Vampyros Lesbos (1971), Les Lèvres Rouges (Daughters of Darkness) (1971) and Lust for a Vampire (1971).

Despite the emergence of new liberated women in the real world, in the cinema of the 1960s and 1970s the trope of woman as victim continued to be peddled; this was evident in the deranged heroine of Repulsion (1965), the harassed pregnant wife of Rosemary’s Baby (1968), the psychological and physical torment of the successful career woman, divorcee and single mother of The Exorcist (1971) and the destruction of a teenage girl upon finding empowerment as a woman in Carrie (1976). Actresses found themselves at the mercy of self-indulgent directors ‘not only for their employment but for their images, images that were ever less rounded and more peripheral’ (Haskell 1987: 326). At the same time depictions of sex and violence began to gain mainstream acceptance with commercially successful productions such as Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Wild Bunch (1969) and Soldier Blue (1970). This had been facilitated by the collapse in 1968 of the Motion Picture Production Code which had attempted, with varying success, to instil moral guidelines in films since the 1930s (it was replaced by the Motion Picture Association of America [MPAA] rating system which rated films’ suitability for audiences based on content). While the relaxation in censorship was liberating for filmmakers, ‘it also liberated parts of the artistic unconscious responsible for sadomasochistic fantasies…[which] increased in brutality and ferocity’ (Rickey 2013).

Alfred Hitchcock’s Frenzy (1972) involves a particularly nasty rape where ‘the woman’s body is fragmented…[with] repeated shots of…ankles and breasts…[suggesting] that, for Hitchcock, woman is little more than the sum of her (sexual) body parts’ (Read 2000: 81). Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) saw Alex (Malcolm McDowell) and his droogs beating and raping his victim while her husband was forced to watch. Equally controversial was Straw Dogs, released the same year with its notorious rape scene which suggests that its victim Amy (Susan George) enjoys it. Director Sam Peckinpah’s misogyny was indisputable in his assertion that ‘there are women and then there’s pussy’ (cited in Prince 1998: 126), i.e. that he viewed the opposite sex as either virgins or whores. Amy’s rape, incidentally, does not appear in the film’s source material, the novel The Siege of Trencher’s Farm. It seemed that ‘the closer women came to claiming their rights and achieving independence in real life, the more loudly and stridently films [asserted that]…it’s a man’s world’ (Haskell 1987: 363). While the new Don Corleone shut his wife out of his machismo world at the end of The Godfather (1972), the protagonist of Looking for Mr. Goodbar (1977) was brutally murdered for daring to be a sexually independent career woman.

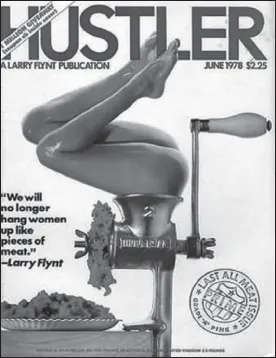

While women were being deliberately punished and marginalised in Hollywood, the same was equally true in low-budget independent productions – with far nastier effect. In The Last House on the Left two teenage girls are tortured and murdered in explicitly graphic detail. Although director Wes Craven always asserted that the film was a serious response to the stylised hyper-violence of Peckinpah and his ilk, a slew of cheap knock-offs followed which had no qualms about revelling in their sexual violence.5 The Texas Chain Saw Massacre saw women hung up on meat hooks, shoved into freezers, bound, gagged and chased with chainsaws (incidentally, the view of women as ‘meat’ was chillingly continued on the cover of Hustler magazine’s June 1978 edition which portrayed a model being churned in a grinder. The appearance of blood around a dead woman’s mouth in La Bestia in Calore (The Beast in Heat, 1977) infers ‘that she has been – quite literally – fucked to death’ (Kerekes and Slater 2000: 80). La Settima Donna (Last House on the Beach, 1978) featured a number of rapes, one of which was disturbingly filmed in slow motion and The Toolbox Murders (1978) married scenes of female masturbation with nail gun slaughter. Violence, as ‘the indispensable staple of male pornography, [was] expressing itself in apocalyptic allegories of male virility’ (Haskell 1987: 364).

Figure 1: Hustler’s infamous June 1978 cover.

Depictions of rape and sexual violence had been a mainstay of less reputable cinemas throughout the 1960s in the form of ‘roughies’ – films which focused on male brutality towards women, particularly involving kidnapping, bondage, sexual assault and murder. In the 1970s these developed into ‘loops’ played in porno theatres, short films of ten to fifteen minutes involving hard-core simulated sex with no narrative. With established directors such as Hitchcock, Peckinpah and Kubrick pushing the envelope ‘artistically’ when it came to sexual violence, the commercial success of Deep Throat in 1972 helped pornography – and misogyny – go mainstream. Deep Throat may have been celebrated for making pornography acceptable in the mainstream but its star Linda Lovelace would later claim that she made the film under duress: ‘every time somebody watches that movie, they’re watching me getting raped’ (cited in Bronstein 2013). In another commercially successful taboo-breaker, Emmanuelle (1974), the eponymous protagonist is raped while watched by her mentor, his lack of intervention inferring that this is all part of the tutoring. The 1970s, quite simply, saw an explosion in the ‘relentless portrayal of sex and violence…[in] grindhouse strips of hard-core sleaze’ (Normanton 2012: 168). With the intended audience at such venues being male, and with American masculinity already threatened by the emergence of strong, independent, sexually assertive women, 1970s exploitation offered an outlet to punish such figures – while providing cheap, non-threatening, titillating thrills along the way.

The decade also saw the emergence of a whole new subgenre of horror film. Condemned by many as encouraging misogynistic violence towards women, it is perhaps no coincidence that the popularity of ‘slash and gash’ movies coincided with the growth of second-wave feminism in America. The genre revelled in depictions of scantily-clad women being sliced and diced by male oppressors, usually with phallic instruments like kitchen knives, axes and machetes. According to film critic Gene Siskel, such movies were ‘some sort of primordial response by some very sick people, of men saying “Get back in your place, women”…Women in the films are typically portrayed as independent, as sexual, as enjoying life, and the killer, typically…is a man who is sexually frustrated with these new, aggressive women’ (1980). No matter where you looked, in real life or on screen, women were continually the victims of sexual aggression perpetuated by men. A small independent film by a first-time director was about to bear the brunt of all that pent-up anger felt by women, critics, the media and politicians about the crimes dished out upon the ‘weaker’ sex.

As Julie Bindel suggests, ‘the feminist movement was at its height when ISOYG was made in 1978, with a plethora of conferences and marches through cities protesting about rape [and] domestic violence’ (2011). Prior to the 1970s it was still legal in some US states for a husband to rape his wife – in fact it was considered his right. A common complaint of rape victims was the insensitive treatment they received from police officers, with the emphasis often placed on what they had done to provoke the assault. Between 1976 and 1984 sex-related murders rose by 160 per cent in the US (see Watkins, Rueda and Rodriguez 1999: 133). Campaign groups such as Women Against Pornography and Women Against Violence Against Women picketed cinemas and condemned ‘women-as-victim films as just another pornographic expression of contempt for women’ (Schoell 1988: 48). The feminist critique of rape was brought to the fore in 1975 with the publication of Susan Brownmiller’s bestseller Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape which argued that rape wasn’t a crime of male frenzied libido but rather ‘a conscious process of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear’ (1977: 15; emphasis in original). Brownmiller recorded that the volume of rapes in the US had increased by 62 per cent over a five-year period (1977: 175). In the same month that ISOYG was released (November 1978), the first Take Back the Night rally, aimed at raising awareness of rape and sexual violence against women, took place in San Francisco. The same year also saw the Privacy Protection for Rape Victims Act signed into law.

It was an era where ‘men got to do anything to women and women got to walk around scared and traumatised and angry’ (Tea 2013: 8); if, as Brownmiller had asserted just three years earlier, the body of a raped woman was a ‘ceremonial battlefield’ and that rape was a war which women could not win (1977: 38, 360), then ISOYG – with its protracted gang-rape of a young career woman – became one of the decade’s first celluloid casualties. The film sent ‘women running and gagging toward the exit’ (Bian 1978). Critic David Keyes declared it his worst film of 1980, describing it as ‘grotesque and repugnant…a work of sexist and unordinary humans, so lacking in human decency that they are the type of people cinema should immediately condemn’ (1980). Gene Siskel was particularly scathing of what he perceived as the film’s misogynistic agenda, condemning it as ‘a very cruel film that expands upon the notion that women are nothing but sexual playthings. Jennifer Hills is portrayed as an independent woman, who strikes out from the Big City to live and work by herself. For this sin against domesticity she is rewarded with the most humiliating kind of violence’ (1980). Siskel’s film critic partner Roger Ebert dismissed it as ‘a vile bag of garbage…without a shred of artistic distinction…sick, reprehensible and contemptible…[and] an expression of the most diseased and perverted darker human nature’; he walked out on the film ‘feeling unclean, ashamed and depressed’ (1980). Both he and Siskel slammed it on their television programme Sneak Previews, choosing it as their worst film of 1980, with Siskel ranking it as the most offensive film he had seen in his eleven years as a critic. In a decade when films like Water Power (1976) featured a sexually deranged rapist fo...