![]()

PART I

Geography and Demography of Rural America

The two chapters in part I set the stage for all the chapters that follow by detailing the changing demography and geography of rural America over time, explaining how poverty rates, poverty policies, and impoverished rural people have changed from the 1930s to today.

Chapter 1, “Where Is Rural America and Who Lives There?,” creates a profile that provides the backdrop for examinations of poverty’s influences on the viability of rural communities, the lives of rural residents, and the contributions rural America makes to the nation’s material, environmental, and social well-being. Rural areas permeate the United States from coast to coast and involve agricultural (farming) lands, struggling industrial (mining and manufacturing) towns, and counties adjacent to urban areas that supply much-needed employment opportunities to commuting rural residents. The chapter also provides definitions for “metropolitan” versus “nonmetropolitan” areas, explains how rural population changes are measured, and most important, traces recent population trends and migration patterns of rural America. The chapter’s unfolding demographic story reveals a rural population that is both aging and becoming more racially diverse.

Chapter 2, “Poverty in Rural America Then and Now,” enriches this backdrop by focusing on changes in rural poverty in the United States from the early twentieth century to the present. Rural poverty first emerged as a policy issue in the 1930s Great Depression, and it resurfaced again in the 1960s War on Poverty. Although fifty years ago rural poverty was widespread across geographic regions and racial groups, by 2015 rural poverty had become increasingly concentrated geographically in “pockets of high poverty,” and impoverished conditions had become more “self-perpetuating,” especially in regions that are home to African Americans, Native Americans, and Hispanics. Today these racial/ethnic minority groups experience the highest poverty rates, and the remote rural counties in which they live are most likely to suffer persistent poverty of place and people. Persistent poverty, particularly among children, is one of the few unchanging characteristics of rural areas.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Where Is Rural America and Who Lives There?

Kenneth M. Johnson

This chapter describes where rural America is and how the population of rural America is changing. Rural America is large and diverse. Some rural areas are growing rapidly, whereas other rural communities house far fewer people today than they did a century ago. Rural concerns are often overlooked in a nation dominated by urban interests. Yet a vibrant rural America contributes to the nation’s intellectual and cultural diversity and provides most of the nation’s food, minerals, clean air, and clean water. The demographic change in rural America has implications for poverty and family well-being. This chapter considers the unfolding demographic story of rural America, setting the stage for the remainder of the book. It examines how poverty influences the viability of rural communities, the lives of rural residents, and the contributions rural America makes to the nation’s material, environmental, and social well-being.

Rural America is a simple term describing a remarkably diverse collection of people and places. More than 50 million people live rurally, and these areas cover nearly 75 percent of the United States. Rural America spans a broad spectrum of landscapes that includes some of the best farmland in the world. It spreads across the vast agricultural heartland of the Great Plains and Corn Belt and extends from the Canadian border deep into Texas. Rural America holds the highly productive fruit and vegetable regions of California, Florida, and the Southwest, as well as dairy regions in Wisconsin, upstate New York, and New England. But there is far more to rural America than agriculture. It includes sprawling exurban areas on the outer edges of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas; the vast arid range and desert lands in the Southwest; the deep, mountainous forests of the Pacific Northwest; the flat and humid coastal plain of the Southeast; the hardscrabble towns and hollows of the Appalachians; the rocky shorelines and working forests of New England, where rural villages look much as they did a hundred years ago; and the glaciers and fjords of Alaska.

Rural economies also depend on more than just agriculture. Some rely on auto supplier plants strung along the interstates of the auto corridor from the Great Lakes to Tennessee. Elsewhere, coal, ore, oil, and gas are extracted, processed, and shipped through a complex network of pipelines, barges, ships, and railroads to urban consumers hundreds or thousands of miles away. Warehouses and distribution centers clustered around major rural interstate interchanges facilitate the movement of goods and products. In other rural regions, struggling industrial towns facing intense global competition try to hold onto jobs and businesses. In contrast, fast-growing rural recreational areas situated near scenic mountains and inland lakes and along the Atlantic, Pacific, and Great Lakes coastlines rush to complete infrastructure improvements needed to support a growing population of amenity migrants, seasonal visitors, and the labor force needed to meet their growing demands.

The diversity of rural America is not limited to its topographical and economic features. The people of rural America also reflect the diverse strands that compose the demographic fabric of the nation. Native peoples reside in ancestral homelands scattered throughout rural areas. Many African Americans still live in the rural Southeast, even though millions moved north in the Great Migration of the early twentieth century. Hispanics are dispersing to the rural Southeast and Midwest from long-established settlements in the Southwest. Despite this growing diversity, large areas of rural America remain overwhelmingly non-Hispanic white. The rural future depends in part on the size, composition, and distribution of the rural population. Demographic change has significant implications for the people, places, and institutions of rural America. It will also influence whether rural areas remain good places to live and raise families and how many rural residents will live in poverty. The remainder of this chapter defines rural America and describes how demographers study population change; examines historical and recent rural demographic change; considers the growing diversity of the rural population by race/Hispanic origin; and explains how the Great Recession influenced rural demographic trends.

WHERE IS RURAL AMERICA AND HOW DO WE MEASURE POPULATION CHANGE THERE?

One important challenge in studying rural America is defining where it begins and where it ends. Clearly, the farm counties of the Great Plains are part of rural America, and New York City is not, but where do we draw the line in between? There is no simple answer. Even the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the federal agency with primary responsibility for rural America, has multiple definitions of which places are rural and which places are urban.

One widely used definition is based on whether a U.S. county is defined as “metropolitan” or “nonmetropolitan.” Why use counties? Counties are a basic unit of government with stable boundaries that don’t change over time. A great deal of demographic and economic data is collected by county.

Counties are also the basic building blocks for metropolitan areas. These metropolitan areas are the collections of cities and suburbs that are referred to as “urban areas.” Counties are designated as metropolitan (urban) or nonmetropolitan (rural) using criteria developed by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget. Rural America is always changing, so definitions of rural America also change. To keep the definition of what is rural stable for this chapter, a constant 2004 metropolitan or nonmetropolitan classification is used.

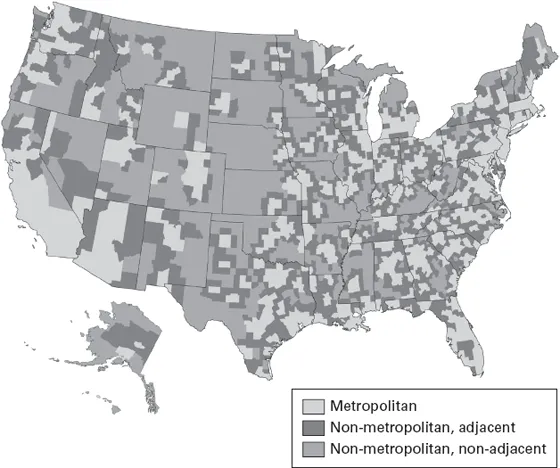

Metropolitan areas include counties with an urban core (city) population of 50,000 or more residents, along with adjacent counties (the suburbs) that link to the urban core by commuting patterns. There are 1,090 metropolitan counties among the 3,141 counties in the United States. All counties that are not within metropolitan areas are grouped together and referred to as nonmetropolitan, even though they differ from one another just as dense urban cores differ from the thinly settled suburbs in metropolitan areas. Our interest is in these 2,051 counties that are not part of metropolitan America (figure 1.1). These are the nonmetropolitan or rural counties that are examined in this chapter. Here the terms “rural” and “nonmetropolitan” are used interchangeably, as are the terms “metropolitan” and “urban.”

Figure 1.1 Metropolitan and adjacent counties.

Source: USDA Economic Research Service, 2004.

Prior research suggests that rural areas near urban areas (adjacent nonmetropolitan counties) have fared better both economically and demographically than counties that are more remote from urban areas (nonadjacent counties). The economic activities in rural counties also differ. Some rural counties depend on farming; others have manufacturing plants; and still others attract tourists to their natural landscapes, lakes, and mountains. Subsets of rural counties are classified using typologies developed by the Economic Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA, ERS), which group nonmetropolitan counties along economic and policy dimensions (for example, farm counties, manufacturing counties, recreational counties, etc).1

MEASURING RURAL POPULATION CHANGE

Some rural counties have gained population for decades, whereas other counties, including many in the agricultural heartland, have lost people and institutions. A key question is: How does the population of one area grow while another area declines?

Population change in rural areas reflects a balancing act between two demographic forces. The first of these is what demographers call natural increase. Natural increase is the difference between the number of babies born in an area and the number of people who die there (births minus deaths). In the United States as a whole, more babies have been born each year than the number of deaths, so the population has always grown from natural increase. In some parts of rural America, however, there have been times when more people have died than been born. When deaths exceed births, demographers call it natural decrease.

The other force that influences population change is migration. Migration measures the movement of the population from place to place. Migration includes both immigration (when people move between countries) and internal migration within the United States. So, how far do you have to move to be a migrant? If a person moves from one U.S. county to another, he or she is referred to as an internal (or domestic) migrant. If the person stays in the same county, he or she is a mover, but not a migrant.

Demographers are particularly interested in net migration. Net migration is the difference between the number of mi...