![]()

Part I

EVOLUTION AND THE FOSSIL RECORD

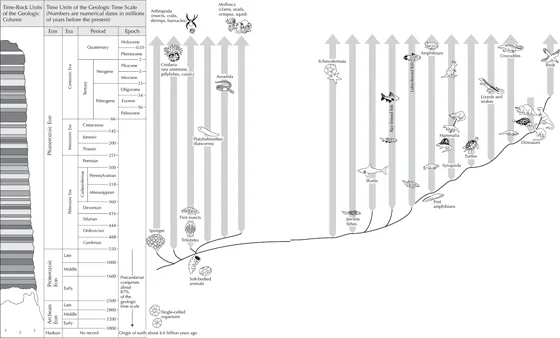

The modern geologic time scale (left) and a simplified “tree of life” showing the branching sequence of the major groups of modern animals. Contrary to creationist “flood geology” misconceptions, most lineages of primitive marine animals are not just found on the lower strata, but span all of geologic time, and have modern representatives as well.

![]()

What Is Science?

The great tragedy of science—the slaying of a beautiful hypothesis by an ugly fact.

—Thomas H. Huxley

There are many hypotheses in science which are wrong. That’s perfectly alright; they’re the aperture to finding out what’s right. Science is a self-correcting process. To be accepted, new ideas must survive the most rigorous standards of evidence and scrutiny.

—Carl Sagan

Before we discuss evolution and the fossil record in detail, we must clear up a number of misconceptions about what science is—and isn’t. Many people get their image of science from Hollywood stereotypes of the “mad scientist,” fiendishly plotting some diabolical creation with a room full of bubbling beakers and sparking electrical apparatuses. Invariably, the plot concludes with some sort of “Frankenstein” message that it’s not nice for science to mess with Mother Nature. Even the positive stereotypes are not much better, with nerdy characters like Jimmy Neutron and Poindexter (always wearing glasses and the obligatory white lab coat) using the same bubbling beakers and sparking equipment but trying to invent something new or good.

In reality, scientists are just people like you and me. Most of us don’t wear lab coats (I don’t) or work with bubbling beakers or sparking Van de Graaff generators (unless they are chemists or physicists who actually work with that equipment). Most scientists are not geniuses either. It is true that, on average, scientists tend to be better educated than the typical person on the street, but that education is a necessity to learn all the information that allows a scientist to make discoveries. Still, there are geniuses, like Thomas Edison, who had minimal formal education (he only attended school for a few months) but a natural instinct for invention. So education is not always required if you have talent to compensate. Scientists are not inherently good or evil; nor are they trying to create Frankensteins, invent the next superweapon, or tamper with the operations of nature. Most are ordinary people who have the interest and curiosity to solve some problem in nature, and rarely do they discover anything that might threaten humanity.

Scientists are not characterized by who they are or what they wear, but what they do and how they do it. As Carl Sagan put it, “Science is a way of thinking much more than it is a body of knowledge.” Scientists are defined not by their lab equipment but by the tools and assumptions they use to understand nature—the scientific method. The scientific method is mentioned even in elementary school science classes, yet most of the public still doesn’t understand it (possibly because the mad scientist Hollywood stereotype is more powerful than the bland material from school). The scientific method involves making observations about the natural world, then coming up with ideas or insights (hypotheses) to explain them. In that regard, the scientific method is similar to many other human endeavors, such as mythology and folk medicine, which observe something and try to come up with a story for it. But the big difference is that scientists must then test their hypotheses. They must try to find some additional observations or experiments that shoot their idea down (falsify it) or support it (corroborate it). If the observations falsify the hypothesis, then scientists must start over again with a new hypothesis or recheck their observations and make sure that the falsification is correct. If the observations are consistent with the hypothesis, then it is corroborated, but it is not proven true. Instead, the scientific community must continue to keep looking for more observations to test the hypothesis further (fig. 1.1).

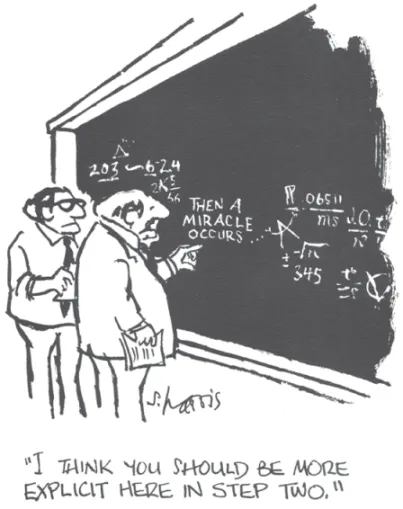

FIGURE 1.1. Scientists cannot revert to supernaturalism and invoke miracles, or their explanations will lead nowhere. (Cartoon courtesy Sidney Harris)

This is where the public most misunderstands the scientific method. As many philosophers of science (such as Karl Popper) have shown, this cycle of setting up, testing, and falsifying hypotheses is unending. Scientific hypotheses must always be tentative and subject to further testing and can never be regarded as finally true or proven. Science is not about finding final truth, only about testing and refining better and better hypotheses so these hypotheses approach what we think is true about the world. Anytime scientists stop testing and trying to falsify their hypotheses, they also stop doing science.

One of the reasons for this is the nature of testing hypotheses. Lots of people think that science is purely inductive, making observation after observation until some general scientific law can be inferred. It is true that scientists must start with observations, but they do not arrive at scientific principles from induction. As Charles Darwin himself put it in 1861,

About thirty years ago there was much talk that geologists ought only to observe and not theorize; and I well remember someone saying that at this rate a man might as well go into a gravel-pit and count the pebbles and describe the colours. How odd it is that anyone should not see that all observation must be for or against some view if it is to be of any service! (1903, 1:195)

Darwin correctly points out that all useful observations must be made in the framework of a hypothesis. What data are needed to test the hypothesis? How will they be useful in falsifying or corroborating it? Instead of inducing general principles of nature, most science is about deductive reasoning: we set up (deduce) a hypothesis, then try to test it. Philosophers use the cumbersome term “hypothetico-deductive method” to describe this process, but it is simple when you think about it.

The difference between inductive generalization and deductive hypothesis testing is easy to illustrate. Suppose we make the inductive statement that “all swans are white.” We could observe thousands of swans for many years but never prove that statement true. All it takes is one nonwhite swan and we can easily falsify this hypothesis. Indeed, there are black swans (fig. 1.2) in Australia and elsewhere, so the statement has been falsified. As Karl Popper pointed out, there is an asymmetry between verification and falsification. It is easy to falsify something; all we need is one well-supported observation that proves the hypothesis wrong. But we can never prove something true (verify it). Additional corroborating observations may support the hypothesis but never finally prove it true. As Popper put it in the title of a book, science is about conjectures and refutations.

FIGURE 1.2. Not all swans are white. This is the Australian black swan. (Photo by the author)

Most people think that science is about finding the final truth about the world and are surprised to find that science never proves something finally true. But that’s the way the scientific method works, as philosophers of science have long ago demonstrated about the logic of the scientific method. Science is not about final truth or “facts”; it is only about continually testing and trying to falsify our hypotheses until they are extremely well supported. At that point, the hypothesis becomes a theory (as scientists use the term), which is a well-corroborated set of hypotheses that explain a larger part of our observations about the world. Some well-known and widely accepted theories are the theory of gravitation, the theory of relativity, the germ theory of disease, and of course, the theory of evolution.

As people, scientists must use common speech as well. An observation or explanation that is extremely well supported is a fact in everyday language (even though we technically cannot use the term within science). As we will discuss below, the evidence supporting the hypothesis that life has evolved (and is still evolving now) is so overwhelming that it is a fact in popular parlance. But the bigger problem is the different usages of the word “theory.” As we just explained, to a scientist, a theory is an extremely well-supported framework of hypotheses that explains a large part of nature. But the public uses the word entirely differently to describe some sort of wild idea or harebrained guess or conjecture, such as theories of how and why John F. Kennedy was assassinated, or how aliens landed in Area 51 in Nevada or Roswell, New Mexico, and the entire episode was covered up by the U.S. government.

This confusion between the scientific and vernacular use of the same word has been a common problem with misunderstanding what evolution is about. As Isaac Asimov put it, “Creationists make it sound as though a ‘theory’ is something you dreamt up after being drunk all night.” For example, then-presidential candidate Ronald Reagan (speaking about evolution during his 1980 campaign) said, “Well, it is a theory. It is a scientific theory only, and it has in recent years been challenged in the world of science—that is, not believed in the scientific community to be as infallible as it once was.” Reagan (perhaps playing to his fundamentalist audience) was voicing the common confusion in the public mind about the two uses of the word “theory.” To scientists, a theory is extremely well supported, has survived hundreds of tests and potential falsifications, and is accepted as a valid explanation of the world. But Reagan is confusing that meaning with the everyday meaning of theory as a “wild harebrained scheme.” He is also showing his ignorance of another aspect of science. Science is always about challenging hypotheses and trying to test them and never reaches a point where a scientific idea is “believed” or is “infallible.” These are words used in dogmatic belief systems, not in science. If scientists stop challenging theories and hypotheses, they stop doing science.

There is also another public confusion embedded in this quote: the confusion between the fact of evolution and the theory of evolution. The idea that life has evolved (and we can still see it evolving) is as much a descriptive fact about nature as the fact that the sky is blue. This was already established long before Darwin and represents an empirical observation about nature, and it is no longer disputed within the scientific community. What Darwin provided was a theory that included a mechanism for evolution he called natural selection. There has always been debate within the biological sciences about whether that mechanism is sufficient to explain the fact that life has evolved and is evolving. Argument and dispute is good in science; it’s a sign that dogmas are being challenged and that no hypothesis is being accepted without question. But even if Darwin’s mechanism, the theory of natural selection, were to be rejected by scientists, it would not change the fact that life has evolved. It is comparable to the theory of gravitation. We still do not have a full understanding of the mechanism by which gravity works, but that does not change the fact that objects fall to the ground.

Science and Belief Systems

A central lesson of science is that to understand complex issues (or even simple ones), we must try to free our minds of dogma and to guarantee the freedom to publish, to contradict, and to experiment. Arguments from authority are unacceptable.

—Carl Sagan

Humans have many systems of understanding and explaining the world besides science. In most cultures, religious beliefs provide the role of explaining how and why things work (“the gods did it”), and until the Enlightenment and Scientific Revolution, these beliefs tried to explain the physical and biological world. In some parts of the world, Marxism is the official “state religion,” and every aspect of life is subjected to “dialectical materialism” and viewed through a Marxist filter. Likewise, there are many organizations (some would call them “cults”) that explain the world through unusual perspectives, such as claiming that aliens are responsible for most of what we don’t understand. These belief systems are not necessarily good or bad, but they are not science, because they are not testable and their main ideas cannot be falsified. Whenever a religious or Marxist dogma is challenged by some observation, that inconvenient fact is explained away or dismissed or ignored altogether, because maintaining the belief system is more important than allowing any inconvenient facts to undermine it. Many people find great comfort in such belief systems. That’s fine, as long as they don’t call these ideas “scientific.” People around the world believe a wide variety of things, and they are entitled to do so. As long as they don’t endanger themselves or others, that’s OK.

The main exception, of course, is when a belief system is detrimental to the believers or to other people. There are cults of “snake handlers” in the Appalachians who caress poisonous rattlesnakes and copperheads during their religious ceremonies with the conviction that God will protect them from snakebite—and they are regularly bitten and killed (70 of these snake handlers have died from snakebites in the past 80 years, including the founder of the cult). In Darwinian terms, this belief system is so hazardous to the believers that they will eventually die out, and a harsh form of natural selection will weed out this self-destructive religion. There are cults that commit ritual suicide, such as Jim Jones’s Peoples Temple, whose members drank cyanide-laced Kool-Aid in the Guyana jungle, killing 913 people in 1978, or the Heaven’s Gate cult, with 39 people committing ritual suicide in 1997 at the urging of their leader, believing that aliens were about to take them to heaven. Likewise, there are ascetic monks who starve themselves to death or stare into the sun in search of enlightenment until they are blind; they, too, are harming themselves and endangering their own survival. Some would say that religious wars, such as the continual battles among Christians, Muslims, and Jews that have plagued the Middle East for over 1,000 years, or the Catholic-Protestant warfare in Ireland, or over much of Europe since the Reformation, or the horrors of the Inquisition, or the Muslim-Hindu wars in India since before Pakistan split away, are arguments that religious belief systems can be murderous and detrimental to the believers.

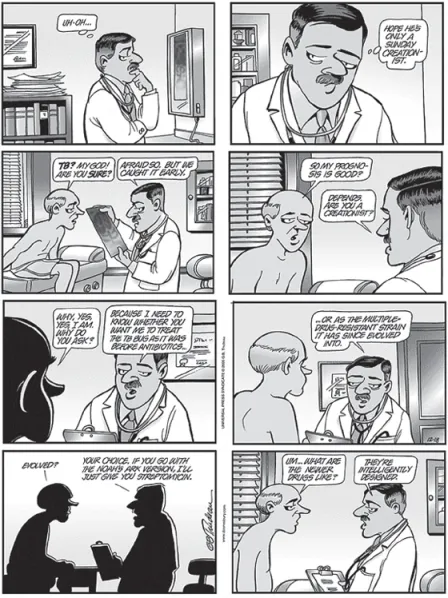

Many people who have strong belief systems that seem to conflict with science want it both ways. They accept their belief system in explaining most aspects of the world but still accept scientific explanations and advances where and when they need them. Some people in the Western world depend on modern scientific medicine for their improved health and chances of survival, yet they refuse to accept important aspects of science (fig. 1.3) that are a part of that great improvement in medicine (such as the rapid evolutionary change that makes viruses and bacteria dangerous to us each year). As Carl Sagan (1996:30) put it, “If you want to save your child from polio, you can pray or you can inoculate.” Extreme fundamentalists push a strange model of the earth (discussed in chapter 3); they call it “flood geology”—yet, if they had any firsthand practical experience with real geology and accepted the results, they would see the absurdity of flood geology. More importantly, they would not benefit from the oil, coal, and natural gas that modern geology has provided all of us, and which flood geology would have no chance of discovering.

FIGURE 1.3. This Doonesbury cartoon eloquently expresses the inherent hypocrisy of the creationists, who try to have it both ways. They reject science and evolution, except when it benefits them. (Cartoon by G...