![]()

Seven Steps to Shapeholder Success

WE HAVE SEEN THE dangers of not incorporating the concerns of shapeholders into your strategic decision making. So how is it best done?

Managers have so many responsibilities when they chart the course of their businesses that they often leave out important considerations or delay timely actions. This is particularly the case when engaging shapeholders—they are unfamiliar to many businesspeople, they typically travel in different circles, and business incentives drive a short-term focus that leaves longer-term shapeholder concerns beyond the horizon.

To help, I will outline the “seven steps to shapeholder success,” all beginning with the letter A—steps that take a long-term view of the best path. The first set of A’s—align, anticipate, and assess—define how to position yourself alongside shapeholder actions.

• Align. A company must align itself with the goal of delivering profit and social benefit. Effective engagement requires credibility with shapeholders. Given the history of businesses engaging nonmarket forces tactically, even disingenuously, there is understandable skepticism to overcome. So to establish authenticity with shapeholders you must align your company with a purpose.

• Anticipate. It is critical to anticipate the concerns of shapeholders and possible nonmarket crises that may erupt. This not only prepares a company to fend off assaults by activists but can often shed light on how to eliminate vulnerabilities and address legitimate concerns. The key is to expect the unexpected. Along with exploring downside risks, a company should look out for upside opportunities to create shared value.

• Assess. For each issue that springs up, a company should assess the legitimacy of shapeholder claims and whether activism or collaborative efforts will prevail.

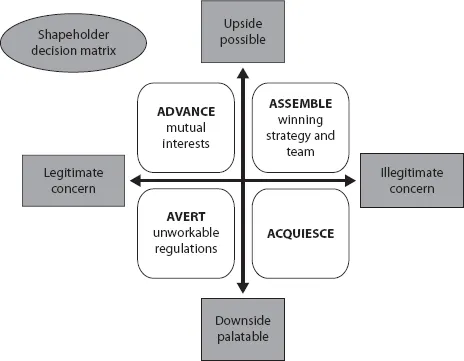

The second set of A’s—advance, avert, acquiesce, and assemble—shows how to act in response to an attack from or opportunity offered by shapeholders.

When considering how to pick a strategy for addressing the different challenges and opportunities that shapeholders present, the “shapeholder decision matrix” is our guide. The key metrics come from the assess step: Is the claim legitimate? Is there an upside for the company?

• Avert: If we assess that the shapeholder claim is legitimate but there is no upside for the company, we should avert potentially negative outcomes by proposing solutions that address the legitimate claim.

• Acquiesce: If we face an illegitimate demand from a shapeholder that we cannot profitably rebut, it may make sense to acquiesce.

• Advance: In the case of a legitimate concern in which an upside exists for the company, we should advance shared interests.

• Assemble: If the cost to acquiesce to an illegitimate issue is prohibitive, or the company believes it can prevail, it is best to assemble a coalition of allies with common cause to ensure success if a confrontation results. Succeeding in such face-offs requires optimizing why, what, where, who, how, and when. Businesses should do the same when industries or industry segments are engaged in political contests.

I dreaded coming home with a report card with anything other than straight As. But I will let you in on a little secret: my mother was a kittycat compared to the shapeholders who will call you out when you don’t pay attention to each of these seven A’s. If you fail to prepare, prepare to fail.

Note that delaying these steps reduces the benefit of company action while increasing the penalty the company would incur if forced to act later. It is often a case of pay me now or pay me more later.

Guardrails, Not Ambulances

Too often businesspeople don’t understand how vital it is to avoid conflict with shapeholders. Brian Mattes from the Vanguard Group told me that he advises his fellow executives, “I’d rather put up guardrails than line up ambulances at the bottom of the hill.” The seven steps will identify the hills and steep curves in your operations and where to put up guardrails.

I think the challenge Western companies have is that they focus only on the last A—assembling for battle. We follow the Carl von Clausewitz approach to conflict: decisive battles seeking conclusive results. Effective shapeholder engagement requires embracing the Eastern thinking of Sun Tzu in The Art of War. Sun Tzu wrote, “The skillful leader subdues the enemy’s troops without any fighting.”

Integrated Strategy

Too often, shapeholder strategy is simply unfocused charitable activities and engaging with shapeholders as a nuisance, reflexively and insincerely. A company would not dream of launching a new product line without a plan that was well thought out and vetted at the highest levels of the company so that everyone knows what the company intends with this new line. But if a company wants to avoid shapeholder disruption, advance a trade agreement, or alter a regulation or debilitating tax, it often has no cohesive plan.

Clearly defined shapeholder strategy is vital in regulated industries, although shapeholders are increasingly active in all industries. And while they may not target your company specifically, they likely have significant influence over your customers or suppliers.

The importance of shapeholder strategy changes over time. The Internet at one time was nearly immune to government influence. Today, issues like privacy, taxation of e-commerce, and the protection of intellectual property have made shapeholder engagement critical to high-tech companies. Anticipating and influencing the direction of change in the shapeholder environment and capturing the opportunities it creates requires an integrated strategy.

We will consider the seven steps sequentially, although we should think of them as iterative. Constantly feeding back results of the later steps to refresh thinking when considering the first steps is essential. The coalition partners you must assemble to win should be included in efforts to build relations to anticipate developments in broader society.

Your strategic planning must include both playing to be remembered in the marketplace and writing the future by effectively engaging shapeholders in the nonmarket arena. The result of your plan to implement these seven steps to shapeholder success must integrate with your plan to succeed in the market. Shapeholder strategy is most successful when it aligns with and supports the market strategy so closely that it is hard to tell when shapeholder strategy ends and market strategy begins. Great power comes from an integrated strategy.

![]()

6

Align with a Purpose

If you lose your purpose…it’s like you’re broken.

—HUGO CABRET, THE MOVIE HUGO

THE PARADOX OF PROFIT says that if you seek, as Milton Friedman advocated, to maximize profit for your shareholders, you must pursue what benefits society as a whole. That twofold direction, which benefits a company’s bottom line and society, is its purpose. Society imposes costs on businesses that do not provide social benefits and offers profitable opportunities to those who do. Businesses that ignore shapeholders risk the costly disruption that Nike faced over labor standards and, worse still, the fate of Arthur Andersen. They also miss opportunities to marshal shapeholder energy to propel them forward, like Starbucks and Whole Foods have done to their benefit.

An authentic purpose springs from a company’s core competencies that drive its profits. This is the best path for your company—and society. When Nike promotes physical activity to combat obesity and Anheuser Busch InBev promotes clean water, each company and society are better off. As people become more fit, Nike sells more shoes and clothing. AB InBev needs clean water in the many nations around the world in which it operates to produce the beer it sells.

Align for Authenticity

Once your purpose is set, you must be devoted to achieving it by aligning your operations toward its fulfillment. My life has shown me the benefits of authenticity and the penalties of inauthenticity.

After graduating with my MBA from the University of Michigan, I joined the Corporate Development Department at Pillsbury. We gave code names to our acquisition targets so that our fellow workers would not know what company we were trying to buy. The code name for the first acquisition I worked on was “Overrun.” Overrun refers to the amount of air that is injected into ice cream as it is being made. Yes, it’s true. If you allow most ice cream to melt, the liquid will fill only part of the container. The fact that the entrepreneurial company in New Jersey we called Project Overrun did not inject air into its ice cream gave the product a creamy smooth taste that melted in your mouth. Let the ice cream melt, and it would fill up the container.

Others sold ice air-and-cream. Overrun’s authenticity, that it sold just ice cream, was the secret to its success. That is the aim every company should strive for. That company’s real name—Häagen-Dazs.

The purpose you define for yourself becomes the foundation on which your reputation rests. Do you have a reputation for selling air as ice cream or selling ice cream?

Reputation is earned by authentic actions, not by spin. My young son Charles enjoyed spending time in the toy and sporting goods departments of ShopKo stores after his Little League games while I did unscheduled inspections as an executive of the company. As we drove home one afternoon, Charles said, “You know, retail is just like baseball. Every day you start zero to zero. Even though the people were happy with you yesterday, if you don’t perform today, you do not win. You have to win every day.”

Charles’s words are true not just about baseball and retail. They apply to how businesses should engage with shapeholders. Every employee, every day, must engage with shapeholders consistent with the company’s commitments and purpose. Reputation is like a fine crystal vase—it takes a long time to build, but seconds to break.1

BP found this out the hard way. After having unfurled a new global brand motto, Beyond Petroleum, with much fanfare a decade earlier, an explosion on BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig on April 20, 2010, killed eleven and caused the largest offshore oil spill in U.S. history. The world’s attention was fixed on the immense damage inflicted on nature and the fishing and tourist industries along the Gulf Coast.

The year of the spill, the company’s brand was removed from the index of the world’s hundred most valuable brands. Julian Dailly, director of valuation at Interbrand London, described the ratings fall: “BP failed to execute on the standards they talked so proudly about in the press and the majority of the company’s brand value has been destroyed as a result.”2 Its brand deteriorated so far that activists protested the Tate Art Museum in London for accepting contributions from BP.3

When a judge approved a $20 billion settlement relating to claims from the spill in 2016,4 reflecting just part of the $56.4 billion BP had set aside to cover costs related to the disaster,5 BP’s misstep was still hurting its reputation. Reports blaming the spill for baby dolphins dying6 and a movie entitled Deepwater Horizon kept the story of BP’s misdeed alive.7

What a mess. BP found out the hard way that saying one thing and doing another leads to charges like greenwashing and leaves you worse off. The intense response to the inconsistencies between BP’s statements and it actions proves the general public has seen this movie several times before.

Align to Avoid Mission Creep

How can a company’s purpose align with its market strategy in a way that delivers social good but keeps it from being society’s ATM?

A logistics company’s market strategy was to be the best in the world at affordably delivering freight—rain or shine—in a timely manner. Society benefits from the low costs and more reliable access to goods and services this company provides. The company defines its purpose as “improving people’s lives through affordable and timely freight delivery.”

A global foundation brought together this logistics company and NGOs to map out a strategy for helping people in need during natural disasters. The logistics firm agreed during the meeting that it would help streamline the process by optimizing the logistical flow of relief through available airports and roads—even when damaged or of insufficient scale. By applying its expertise in this area, the logistics firm brought more aid to more people, saving lives.

Even though the logistics firm had agreed to help, a representative from an NGO was angry with the logistics firm, because it would not say that the firm’s purpose was to save lives. The logistics company was obviously happy to save lives, but there are many other ways the firm could work toward that goal—funding food for starving children, providing clean water for those without it, or supplying maternal health care in impoverished regions. If the firm were to define its purpose as “saving lives,” it would obligate itself to contribute its resources to every such proposal, even if the effort had not even a remote connection to the company’s capabilities and strategy.

It makes sense for a food company to have a purpose that includes feeding starving children or for a water systems company to have a purpose that includes providing drinking water to all or for a health-care provider to have a purpose including bringing maternal health care to impoverished regions. But it doesn’t make sense to expect any of those things from a logistics company.

Rather, the logistics firm’s aim should be to engage with society in ways that mesh with and support its market strategy and purpose. It can improve peopl...