![]()

1

The Promise and Threat of Reproducibility

Philippe Parreno’s use of the disposable DVD-D format in Precognition (2012) engages at once in an embrace of access, something that has historically been extremely important to artists working in film and video, and attempts to maintain authorial control over the work through the inclusion of a chemical that will render the disc unplayable after it has been watched once. Precognition thus takes up a conflicted position in relation to the possibilities of circulation enabled by digital forms of reproduction, finding in them both hope and menace. While Parreno’s gesture depends on the specific technical affordances of the DVD-D support, this attitude toward reproducibility is by no means particular to the digital moment. The tension it dramatizes is not novel but rather must be seen as reigniting and reanimating an old friction through new technologies.

The fear of the copy is ancient: in making a fundamental distinction between form and matter, Plato established an enduring tradition of conceiving of the copy as an imperfect imitation of the elevated original, forever marred by an inescapable secondariness. While this schema remains influential, the Platonic dichotomy is insufficient for characterizing the profound ambivalence that surrounds the reproducible image. It offers only a reason to denigrate the copy, not one to praise it. In the nineteenth century the advent of photographic processes such as the calotype—able to produce multiple positives from a single negative—initiated a new culture of image production and circulation that occurred alongside a massive reorganization of the fabric of life. Industrial modernity reconfigured the relationship between original and copy, displacing the idealism of the Platonic conception with a new, immanent materialism. Unlike the transcendental, atemporal status of Plato’s forms, now the original resides in this world, on the same plane as the copy. The two might even meet one another, dynamically interacting in scenes that pit the allure of rarity against the principle of access. The original might be threatened by the copy, or it might find its status reaffirmed or even augmented by it. Under this regime the copy could remain lowly, insulting, and secondary, but it could just as easily be unshackled from any attachment to an original and championed for its mass reach.

The moving image is inherently reproducible, but to chart the shifting and plural meanings of this reproducibility, one must examine how film and video have been discursively constructed, as well as how these discursive formations have evolved over time. Indispensable to the articulation of this protean character of reproducibility is a concept that stands in an antithetical relationship to it: authenticity. A veritable nineteenth-century obsession, authenticity provides a means of elucidating the connection between the modern subject and the world of things. It illuminates precisely why a phobia of new forms of reproduction takes hold circa the advent of photography and cinema but also sheds light on why these technologies are equally thought to harbor a utopian potential. It is to this moment and this concept that one must look to discern the formation of the discourses that first shaped the position of the moving image vis-à-vis traditional artistic media and that continue to do so in the contemporary moment, when a desire for authenticity remains in force despite decades of assault on varied fronts. The following pages will explore how new forms of image reproduction both challenged and inspired the privileging of authenticity during two periods some one hundred years apart: the early years of cinema and the digital dissemination of moving images at the threshold of the twenty-first century. In both instances one sees the simultaneous promise and threat of the copy rear its head: it offers greater access and availability but also threatens to liquidate uniqueness and historicity. Thomas Elsaesser has suggested that there is a tremendous value in developing a “bifocal perspective on the cultural fabric that is cinema around 1900 and 2000,” for it allows for a consideration of how these two moments of immense technological and social change offer productive points of comparison and contrast with one another.1 This chapter will take up this methodology, seeking thereby to theorize how and why the circulatory reproducibility of the moving image has figured as both promise and threat across the decades.

The Soulless Copy

Already in 1759, Edward Young asked, “Born Originals, how comes it to pass that we die Copies?”2 This question is rooted in a romantic conviction, associated primarily with the thought of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, that sees society as destructive of the authenticity, goodness, and uniqueness of humankind. In the nineteenth century such ideas found increased currency as new processes of urbanization and mechanization forever altered the subject’s relationship to nature, time, work, and leisure. Industrial modernity proceeded as a rationalization of all aspects of life driven by a capitalist economy, prompting some to see it not as progress but rather as experiential impoverishment. We die copies, to reprise Young’s formulation, after being subject to a lifetime of dehumanization at the hands of society. In this postlapsarian understanding of modernity the copy is particularly denigrated: its mechanical sameness emblematizes precisely the spiritual sickness resulting from the deindividualization that takes place as one becomes a part of the modern masses. Uniqueness becomes something that cannot be taken for granted and must be pursued.

In the mid-nineteenth century, works of literature such as Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1843) and Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street (1853) communicated the extinguishing of the soul experienced by their main protagonists at the hands of the ruling classes by casting the men in the profession of manual copyist.3 Copying is thought to be mere drudgery and is marshaled as a way of pointing to the broader societal transformations that Max Weber called the disenchantment of the world. All of the interconnectedness and fidelity to tradition that had characterized premodern society would now find itself destroyed in the rise of the modern Gesellschaft, in which atomization and self-interest prevailed. Copying is degraded and devalued because of its close ties to standardization. As all difference was collapsed into sameness, the notion of the nonreproducible would be at once thrown into crisis and exalted, while the copy would stand as a metonym for broader processes of rationalization.

Young’s assertion that we are born originals articulates a conviction that we begin life as essentially true to ourselves, before experiencing a progressive estrangement from this state that takes the form of a false outer self concerned with being-for-others—something Jean-Paul Sartre would much later term “bad faith.” Rather than a yearning for originality, this sentiment is better understood as the desire for authenticity. In 1972’s Sincerity and Authenticity Lionel Trilling traces the emergence of the modern conception of authenticity to the mid-eighteenth century and ties it to a perceived impoverishment of experience.4 Drawn from the museum and the connoisseurship of art, authenticity is a polemical concept that seeks to revive a fullness of meaning and an unalienated state of being at a time when increased secularization and industrialization prompted a crisis of absolutes. In the absence of the transcendent and eternal the subject turns inward, taking authenticity as a paragon of personal virtue. The desire for authenticity is, then, first and foremost the desire for an authentic existence, a truth to oneself. It provides a way of guaranteeing the stability of the subject, proposing a notion of self-presence that would come under fierce critique with the advent of poststructuralism. This emphasis on the achievement of subjective uniqueness and consistency is found in the word’s etymology, which combines autos (self) and hentes (to accomplish or to do). Authenticity is thus a subjective ideal invested with a heavy moral weight.

According to Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello, in the nineteenth century authenticity became a key term in the artistic critique of capitalism, which posits the latter as a source of disenchantment and alienation: “This critique foregrounds the loss of meaning and, in particular, the loss of a sense of what is beautiful and valuable, which derives from standardization and generalized commodification, affecting not only everyday objects but also artworks (the cultural mercantilism of the bourgeoisie) and human beings.”5 The valorization of authenticity emerges as a subjective response to mass culture that in turn offers a criterion by which that culture—and the traditional formations it threatened—might be judged. It is a conservative reaction that tends to make recourse to an earlier time, a supposedly primitive state, or traditional modes of production. The authentic is diametrically opposed to the reproducible, its character stemming precisely from its supposed existence outside any regime of fungibility or equivalence. It sits firmly on the side of rarity. As Walter Benjamin wrote, “The whole sphere of authenticity eludes technological—and of course not only technological—reproduction.”6 Art in particular was thought to provide a nourishing reservoir of authenticity within and against the increasing standardization of life under industrial capitalism. Trilling writes, “As for the audience, its expectation is that through its communication with the work of art, which may be resistant, unpleasant, even hostile, it acquires the authenticity of which the object itself is the model and the artist the personal example.”7 Even if the art object is fabricated according to means unaligned with authenticity, as would increasingly occur throughout the twentieth century, it maintains its authentic status through its connection to the figure of the artist as the “personal example” of a life authentically lived. Trilling describes a form of mimetic contagion, whereby the wholeness and integrity associated with the authentic art object—an emanation of the artist’s ownmost being—might be transferred to the viewing subject as if by sympathetic magic. The desire for authentic existence and the valorization of authentic objects and experiences are thus deeply connected: anxiety over the fate of the subject is enacted in the world of objects, as the two enter into a mirrored relationship. Though authenticity is above all a personal virtue, its discursive field extends much farther than the individual, marking out a dynamic relationship between the subject and the object-world of industrialized society.

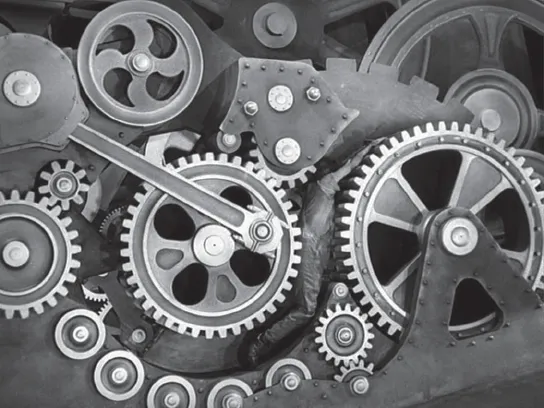

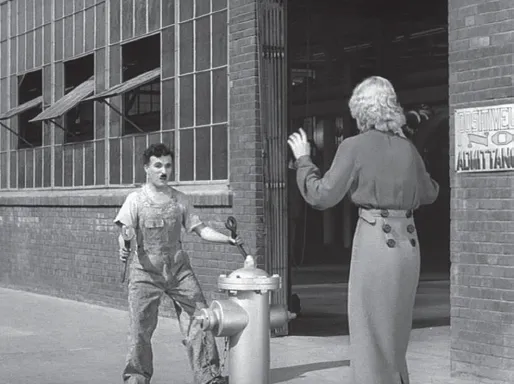

As the emanation of a system of standardization and commodification, the mass-produced image emerges as the epitome of the threat of inauthentic sameness. Its means of production, the machine, is particularly maligned. As Trilling writes, “The anxiety about the machine is a commonplace in nineteenth-century moral and cultural thought…. It was the mechanical principle, quite as much as the acquisitive principle—the two are of course intimately connected—which was felt to be the enemy of being, the source of inauthenticity. The machine, said Ruskin, could only make inauthentic things, dead things; and the dead things communicated their deadness to those who used them.”8 Once again, one encounters here the rhetoric of transfer, this time as the literal deadness of machines transmutes into the metaphorical deadness of the subject. This mistrust of machines arises at a time when many handicraft traditions were being replaced by automation and when the implementation of rationalized manufacturing processes meant that workers no longer made a product start-to-finish but were simply cogs in the wheel of the assembly line. Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1933) captures this fear in an iconic scene, when the worker—after frenetic repetitions on the assembly line—is swallowed into the machine, tightening its gears even while it submits him to bodily violence (figure 1.1). When it spits him out like a finished product, he dances with balletic grace but is unable to distinguish between his interaction with the machine and his interaction with fellow humans. Everywhere he sees nothing but bolts to be secured, even on the buttons of women’s skirts and dresses (figure 1.2). Sameness reigns. His entire existence—including his libidinal drive—has been disciplined into a machinic productivity from which he will derive no profit. While Chaplin makes a mockery of this condition, he points to something serious: the colonization of the totality of the subject by the rationalized processes of industrial modernity. Against such a notion of a lifeless, mechanical assemblage that might swallow up the being of the worker and flatten it into uniformity, supposedly authentic modes of production are marked by an organic wholeness, one that soothes the individual subjected to alienated labor, promising personal fulfillment and the preservation, or even rehabilitation, of uniqueness.

FIGURE 1.1 Modern Times (Charlie Chaplin, 1936). The worker’s body incorporated into the machine.

FIGURE 1.2 Modern Times (Charlie Chaplin, 1936). The worker cannot see beyond the assembly line.

Geoffrey Hartman has written that authenticity is a “value word with complex associations” surrounded by “a swarm of synonyms and antonyms. Authenticity contrasts with imitation, simulation, dissimulation, impersonation, imposture, fakery, forgery, inauthenticity, the counterfeit, lack of character or integrity.”9 It is worth pausing here to consider a word missing from Hartman’s swarm but requiring particular attention in the present context, especially because of its currency in discourses of the artistic sphere: originality. The relationship between authenticity and originality is complex, owing in part to the multiple meanings condensed in the latter. These terms are often used interchangeably to signal that an artwork is not a forgery or an illicit copy. Both share an allergy to reproduction and are frequently taken as grounds for the cultural and economic valorization of an art object. But while there are indeed occasions when they may legitimately function as synonyms and although their respective meanings may in some cases overlap, ultimately these terms designate nonisomorphic qualities. James Elkins has enumerated three nonessential properties for a work of art to be considered original: the status of being originary, that is, appearing to be without antecedent in a given context; primacy, the condition of referring mostly to itself; and uniqueness, the state of being singular rather than multiple.10 A significant difference between originality and authenticity is found in Elkins’s first criterion of originariness and the temporality it implies: originality understood in this sense is engaged above all in a privileging of novelty in that it involves the staking of a new, vanguard position; authenticity, meanwhile, tends to make recourse to a past, whether revived or invented.11 There are, however, instances in which originary works may resonate closely with authenticity in their shared opposition to reproduction and standardization. Pablo Picasso’s Les demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), to take an uncontroversial example, fits all three criteria of originality: it makes an intervention in the advancing history of modernism; it refers primarily to itself; and it is a unique object. Yet it also issues from the artist’s hand, inhabiting a mode of production allied with a time before industrial mechanization. In this case the avant-garde novelty constitutive of the work’s originariness coexists with its authenticity owing to the mode of production employed, which is understood in contrast to industrial automation and replication. Moreover, the painting’s originariness may be understood as an emanation of the unique subjectivity of the artist and thus consonant with the discourse of authenticity. Contrarily, originality and authenticity can just as easily part ways. An object might be authentic in the sense of uniqueness yet lack originariness, as in the case of traditional handicrafts or a retardataire painting. Elkins notes that ar...