- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Many investors believe that success in investing is either luck or clairvoyance. In Rational Investing, finance professor Hugues Langlois and asset manager Jacques Lussier present the current state of asset management and clarify the conundrum of luck versus skill. The core of Rational Investing is a framework for smart investing built around three performance drivers: balancing exposure to risk factors, efficiently diversifying bad luck, and taking advantage of relative mispricings in financial markets. With clear examples from model multi-asset-class portfolios, Langlois and Lussier show how to implement performance drivers like institutional investors with access to extensive resources, as well as nonprofessional investors who are constrained to small-scale transactions. There are few investment products, whether traditional or alternative, discretionary or systematic, fundamental or quantitative, whose performance cannot be analyzed through this framework. Langlois and Lussier illuminate the structure of financial markets and the mechanics of sustainable investing so any investor can become a rational player, from the nonprofessional investor with a basic knowledge of statistics all the way to seasoned investment professionals wishing to challenge their understanding of the asset management industry.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Rational Investing by Hugues Langlois,Jacques Lussier in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Betriebswirtschaft & Finanzwesen. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

BetriebswirtschaftSubtopic

Finanzwesen1

The Subtleties of Asset Management

THIS BOOK IS ABOUT bridging the gap between simplicity and complexity in asset management. It is about providing nonprofessional investors with an understanding of what underlies investment success while still making investment professionals reflect on many issues they may have forgotten or overlooked. It is about achieving these objectives in fewer than two hundred pages because the essence and clarity of a message are often lost in the thickness or the specialization of the medium of communication. And it is a tremendous challenge.

It is a challenge because asset management is an industry in which conflicts of interest are omnipresent, and the conversation is often adjusted to protect the interests of some of the players. In the last twenty years, the asset management industry has not only developed better investment strategies, but unfortunately also ways to package existing investment products and repackage old ideas, often at a higher cost. You may have already heard of the separation of alpha and beta; alpha overlay or transport; alternative, exotic, and now smart beta; fundamental indexing; core versus satellite components; liability-driven investment (LDI); performance-seeking portfolios (PSP); etc. It is a challenge to succinctly present a framework for understanding all of these concepts while each is often improperly pushed as a distinctive breakthrough. It is nonetheless the objective of this book.

It is also a challenge because asset management is not just about financial concepts. It is also about economics more generally, mathematics, statistics, psychology, history, and sociology. A comprehensive investment approach requires a comprehensive understanding of all these fields, a knowledge base few of us have. Investors’ education is therefore both essential and difficult. Building a lasting cumulative body of knowledge requires drawing evidence from many different literatures. The objective of this book is to provide the broadest possible understanding of the factors that drive investment successes and failures while avoiding as much as possible the complexity, biases, and noise that surround it.

For example, in disciplines such as astronomy and physics, we build our body of knowledge through relevant experimentation that hopefully allows for consensus among experts. This process provides a foundation for furthering our understanding through new research. Few physicists would challenge the idea that a body with more mass exerts greater gravity. In contrast, most investors and professional managers believe they are above average. More generally, the interaction between investment research and the financial markets it studies results in a constant evolution of these markets. The complexity of asset management and its interaction with social sciences also implies that it is difficult to build a clear consensus. It is therefore possible for players in that industry to simply ignore empirical evidence and rational thinking if it challenges the viability of existing business models. This is implicitly reflected in the answer given by Jeremy Grantham of GMO when he was asked about what would be learned from the turmoil of 2008: “We will learn an enormous amount in the very short term, quite a bit in the medium term, and absolutely nothing in the long term. That would be the historical precedent.”1

Given these complexities, it is not surprising to see that there is a significant divide between the enormous body of literature developed by financial academicians and the body of research and practices accumulated by practitioners. Once we integrate knowledge from different areas of literature and work hard at making our thinking clean and simple, it becomes easier to explain the sources of success in terms that most investors can understand.

The main objective of this book is to explain all structural sources of performance and to illustrate their implementation. To this end, we cover many topics. We will discuss that there are talented and skilled professional fund managers out there, but that unfortunately not a lot of the value they create ends up in investors’ pockets. We will show that forecasting expected returns is not a useless endeavor, but it is usually not the primary source of sustainable excess performance of successful managers despite the rhetoric.

This book was written with the objective of communicating what is required to invest rationally while making its content accessible to as wide an audience as possible. It avoids the overuse of equations and of complex terminologies. In fact, we have managed to write this entire book with just a few equations. The length limitation we imposed on ourselves also dictates that we concentrate on the most relevant concepts and evidence.

The framework used in this book is not revolutionary, nor do we need it to be. We are not reinventing the wheel. We are presenting an overall picture of asset management through which we are going to underline many subtleties of this fascinating field that can allow us to sustainably outperform others. Investing in financial markets is a lottery only if we do not understand what drives long-term performance.

What This Book Is Not About

This book is not about saying that markets are perfectly efficient or inefficient. Market efficiency says that all the information relevant to the valuation of an investment is reflected in its price. If the price of any asset perfectly reflected its true fundamental value, there would be no point in spending resources trying to spot good investment opportunities to beat the market. Whatever you buy, you get a fair price for the risk you are getting into. But market inefficiency proponents point out that investors are not perfectly rational investing robots. They are influenced by their emotions and behavioral biases, and as a result asset prices can differ from their fundamental values in such a way that riskless profits can be made. Hence an investor could beat the market by looking for good investment opportunities.

It can’t be that easy; prices cannot be completely irrational and erratic. Many smart investors compete with each other to profit from potential market inefficiencies, and few are able to make a killing at it. The reality lies in between. Markets have to be inefficient enough to make it worthwhile for investors to spend time and resources analyzing different investments and looking for good opportunities. But they cannot be so inefficient that it is easy to beat the market. If undervalued securities could be spotted easily, all investors could buy them and push up their prices to a fair level. A similar argument applies to overvalued securities. To borrow the characterization from Lasse Pedersen, professor of finance at New York University Stern School of Business and Copenhagen Business School, markets are efficiently inefficient.2 This book discusses sources of investment profits coming from both sides: rational compensations for the risks supported by investors and irrationalities in financial markets caused by emotions and other behavioral aspects.

On a related note, this book is not about taking sides in the debate between passive and active management. Passive managers simply invest in the market index, that is, a portfolio that includes all assets whose allocations depend on their market capitalization (i.e., their market value), such as buying the S&P 500 Index. Active managers look for good investments and try to beat the market index. Widespread evidence shows that most active managers fail to outperform the market index, and since the first index fund was launched in the 1970s, passive investments have gained in popularity. Exchange traded funds (ETF) now offer the possibility for investors to invest in a wide variety of market indexes at a low cost. Who is right? Again, the reality lies in between. There are talented investors out there and we all have a lot to learn from them. The important issue is how much of their performance actually trickles down to investors’ pockets. For an active fund to be a good investment opportunity, its managers have to be good enough to cover trading costs as well as the management fees that they charge you. Accordingly, this book does not take a stance on whether you should be an active or a passive investor. Rather, it analyzes the factors that should impact your decision.

This book is not about diversification for the sake of diversification. Diversification is said to be the only free lunch in finance. Yet it remains an uncomfortable proposition for many investors. Aren’t we buying bad investments as well as good investments when we are diversifying? Warren Buffett, famous investor and chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, said that “diversification is protection against ignorance. It makes little sense if you know what you are doing.”

Diversification is often misunderstood. Diversification does not require owning thousands of stocks. A good portion of available diversification benefits can be obtained by owning a portfolio of twenty to thirty companies, similar to what Mr. Buffett does. Nor is diversification about sacrificing returns to get lower risk; diversification can actually lead to higher long-term returns through the effect of compounding. Most importantly, diversification is not a substitute for a careful analysis of investment values. Valuation is not trumped by the power of diversification. However if you have a smart way to analyze and pick investments and you care about the level of total risk you are taking in your portfolio, there is little reason for most of us to invest in an underdiversified portfolio of just a few assets.

This book is not about any asset class (stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies, etc.) in particular. There are, of course, specificities to each market. An investment expert who spent his career trading in the government bond market knows this market better than an equity trader (and vice versa). Still, markets are not completely segmented and the investment principles discussed in this book apply broadly. Many investment styles, risk factors, and strategies work in different markets. This book focuses on building efficient portfolios in all traded asset classes using a common investment philosophy.

Finally, this book is not about fundamental investing versus quantitative investing. The former refers to investors who make inferences from their analyses of investment’s fundamentals (cash flows, accounting value, industry trends, macroeconomic conditions, etc.). The latter can refer to investors who rely on statistical methods and computer models to pick investments, often using many of the same fundamental variables. Fundamentals are important. However, whichever emphasis you want to put on fundamentals, it is better to do it by relying on careful quantitative analysis. An investor may have the greatest intuitive skills to pick investments, but we would still prefer to confirm his analysis through careful quantitative analysis. Gut feelings are nice for movies, but very dangerous for successful long-term investing.

The Roadmap to Successful Long-Term Portfolios

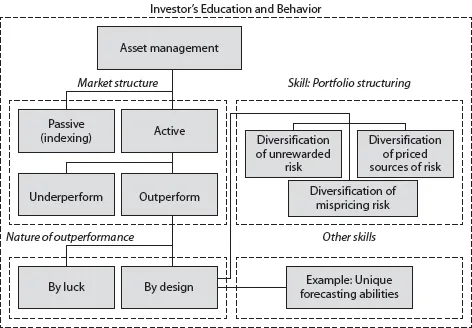

To present the structure of this book, we use the framework set forth in figure 1.1. There are four distinctive blocks in the figure and one that surrounds them all.

The first box in the top left part of figure 1.1 is about the impact of market structure on performance. This is an aspect investors cannot do anything about and it is mainly the subject of chapter 2. Our discussion starts with the first decision you need to make as an investor: Should you be a passive (indexed) or an active investor? Because passive investors mimic the market portfolio, only active investors can potentially do better than the market. However, active investors as a group will do just as well as the market—no better, no worse. Indeed, active and passive investors are the market. In other words, if the market is up by 10 percent, passive investors will be up by 10 percent. Consequently, it goes without saying that all active investors as a group are up by 10 percent as well.

FIGURE 1.1 A schematic to asset management

Hence an active investor can only outperform at the expense of another active investor. Some active investors will underperform while others will outperform. But if you are like us, you are not interested in simply outperforming the market. You are interested in outperforming it consistently. In this book, we want to understand what explains long-term investment successes, not short-term gains mainly due to luck.

Furthermore, to be a successful active investor over the long run, not only do you need to consistently extract value from other active investors, but you must also do it to an extent that covers the extra costs you incur by being an active manager. This is no small feat; at this point you might recognize that you do not possess such expertise. Indeed, for many investors, passive investing, with its low-cost structure, is the best deal in town. Alternatively, you may delegate the management of your portfolio to a professional fund manager. But choosing a skilled manager is far from obvious. Screening the S&P Indices Versus Active (SPIVA) scorecards, you will quickly notice that if you select an active manager at random, you likely have less than three chances out of ten of selecting a manager who will outperform after fees in the long term. The level of expertise that exists in the market does not change this observation.

Chapter 3 closely examines the difficult task of selecting a professional fund manager. The challenge here is to identify talented managers and to be able to do it in advance. Indeed, knowing which managers are good after the fact is pointless. The key issue is to distinguish genuine investing skills from pure luck. Past performance over a short horizon of a few years is often meaningless as proof of a manager’s skills. Standard statistical analyses usually cannot conclude whether a manager is truly skilled after such a short period. Instead, investors must be convinced of the abilities of a manager through an understanding of his process, not by his performance over the last three years. Such confidence requires a deep understanding of relevant structural qualities within portfolios.

Chapter 4 discusses our ability to forecast complex systems such as financial markets, especially the contrast between predictions given by experts and those provided by simple statistical models. For the sake of portfolio allocations, relying on simple statistical models may lead to better forecasts because experts’ forecasts can be tainted by overconfidence and conflicts of interest.

Chapters 2 to 4 are concerned with the desire to outperform the market. We cover three broad possibilities that are not mutually exclusive: being an active investor yourself (chapter 2), hiring a professional fund manager (chapter 3), and relying on forecasts to adjust your portfolio allocation (chapter 4).

The second block in the bottom left part of figure 1.1 deals with the conundrum of the role of luck versus investment skills. This is a recurring topic in several chapters of this book. Indeed, the financial market is an environment in which luck plays a large role in observed performances. By luck we mean investment performance that is due to what statisticians call noise, or pure randomness. Imagine a room with one thousand individuals, none of whom has any investment skill. Each individual is independently asked to determine whether he should overweight Alphabet at the expense of Amazon or the reverse for the next three years. It is likely that approximately half will be right and will outperform even if they have no investment skill. As you may imagine, we want to ensure that the success of our investment strategy does not rely on luck!

We emphasize in this book the long-term aspect of the portfolio management approaches we discuss. Luck (i.e., noise) plays a large role in short-term performance. It still plays a role in long-term performance, but to a lesser extent. To see why, imagine that you have found a strategy that is likely to generate a 10 percent return on average every year (or approximately 0.04 percent every day). But assets, such as stocks, display a lot of daily variability; it is not usual for stocks to vary between −2 percent or +2 percent every day. Hence the part of daily returns that you may explain on average, 0.04 percent, is hard to discern from the daily market noise. Over longer horizons, say one year, most −2 percent daily noise returns cancel out with +2 percent noise returns and your daily average return of 0.04 percent cumulated over the year explains much more of your annual total returns.

As a consequence, an unskilled manager is as likely as a skilled manager to outperform the market if the investment horizon is as short as one day because short-term variations are driven more by noise than by fundamentals. However, a skilled manager is more likely to outperform an unskilled manager if the investment horizon is as long as ten years. Thus, the impact of luck fades over time. Unfortunately, it never totally disappears. This is an unavoidable reality of our investing world.

Investors and managers often significantly underestimate the impact of luck on investment performance. It may cause investors to make allocation decisions that are ill advised and needlessly increase the turnover of managers and strategies in their portfolios. For example, evidence shows that after a few years of underperformance, investors often feel pressured to change their allocation and substitute their managers, quite often with dreadful timing. It may also lead to overconfidence and even arrogance about one’s abilities as an asset manager. The objective of this book is to demonstrate how important it is to untangle the relevant dimensions that explain success or failure in investing.

The bottom left box in figure 1.1 shows that investment outperformance can be attributed to luck, skills, or more realistically to both. Daniel Kahneman, the psychologist winner of the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, said that success is attributed to talent and luck while great success is ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- 1. The Subtleties of Asset Management

- 2. Understanding the Playing Field

- 3. Skill, Scale, and Luck in Active Fund Management

- 4. What May and Can Be Forecasted?

- 5. The Blueprint to Long-Term Performance

- 6. Building Better Portfolios

- 7. We Know Better, But …

- Notes

- Index