eBook - ePub

Extraordinary Bodies

Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Extraordinary Bodies

Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature

About this book

Extraordinary Bodies is a cornerstone text of disability studies, establishing the field upon its publication in 1997. Framing disability as a minority discourse rather than a medical one, the book added depth to oppressive narratives and revealed novel, liberatory ones. Through her incisive readings of such texts as Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin and Rebecca Harding Davis's Life in the Iron Mills, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson exposed the social forces driving representations of disability. She encouraged new ways of looking at texts and their depiction of the body and stretched the limits of what counted as a text, considering freak shows and other pop culture artifacts as reflections of community rites and fears. Garland-Thomson also elevated the status of African-American novels by Toni Morrison and Audre Lorde. Extraordinary Bodies laid the groundwork for an appreciation of disability culture and an inclusive new approach to the study of social marginalization.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Extraordinary Bodies by Rosemarie Garland Thomson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & North American Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Politicizing Bodily Differences

ONE

Disability, Identity, and Representation: An Introduction

The Disabled Figure in Culture

In its broadest sense, this book investigates how representation attaches meanings to bodies. Although much recent scholarship explores how difference and identity operate in such politicized constructions as gender, race, and sexuality, cultural and literary criticism has generally overlooked the related perceptions of corporeal otherness we think of variously as “monstrosity,” “mutilation,” “deformation,” “crippledness,” or “physical disability.”1 Yet the physically extraordinary figure these terms describe is as essential to the cultural project of American self-making as the varied throng of gendered, racial, ethnic, and sexual figures of otherness that support the privileged norm. My purpose here is to alter the terms and expand our understanding of the cultural construction of bodies and identity by reframing “disability” as another culture-bound, physically justified difference to consider along with race, gender, class, ethnicity, and sexuality. In other words, I intend to introduce such figures as the cripple, the invalid, and the freak into the critical conversations we devote to deconstructing figures like the mulatto, the primitive, the queer, and the lady. To denaturalize the cultural encoding of these extraordinary bodies, I go beyond assailing stereotypes to interrogate the conventions of representation and unravel the complexities of identity production within social narratives of bodily differences. In accordance with postmodernism’s premise that the margin constitutes the center, I probe the peripheral so as to view the whole in a fresh way. By scrutinizing the disabled figure as the paradigm of what culture calls deviant, I hope to expose the assumptions that support seemingly neutral norms. Therefore, I focus here on how disability operates in culture and on how the discourses of disability, race, gender, and sexuality intermingle to create figures of otherness from the raw materials of bodily variation, specifically at sites of representation such as the freak show, sentimental fiction, and black women’s liberatory novels. Such an analysis furthers our collective understanding of the complex processes by which all forms of corporeal diversity acquire the cultural meanings undergirding a hierarchy of bodily traits that determines the distribution of privilege, status, and power.

One of this book’s major aims is to challenge entrenched assumptions that “able-bodiedness” and its conceptual opposite, “disability,” are self-evident physical conditions. My intention is to defamiliarize these identity categories by disclosing how the “physically disabled” are produced by way of legal, medical, political, cultural, and literary narratives that comprise an exclusionary discourse. Constructed as the embodiment of corporeal insufficiency and deviance, the physically disabled body becomes a repository for social anxieties about such troubling concerns as vulnerability, control, and identity. In other words, I want to move disability from the realm of medicine into that of political minorities, to recast it from a form of pathology to a form of ethnicity. By asserting that disability is a reading of bodily particularities in the context of social power relations, I intend to counter the accepted notions of physical disability as an absolute, inferior state and a personal misfortune. Instead, I show that disability is a representation, a cultural interpretation of physical transformation or configuration, and a comparison of bodies that structures social relations and institutions. Disability, then, is the attribution of corporeal deviance—not so much a property of bodies as a product of cultural rules about what bodies should be or do.

This socially contextualized view of disability is evident, for example, in the current legal definition of disability established by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990. This landmark civil rights legislation acknowledges that disability depends upon perception and subjective judgment rather than on objective bodily states: after identifying disability as an “impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities,” the law concedes that being legally disabled is also a matter of “being regarded as having such an impairment.”2 Essential but implicit to this definition is that both “impairment” and “limits” depend on comparing individual bodies with unstated but determining norms, a hypothetical set of guidelines for corporeal form and function arising from cultural expectations about how human beings should look and act. Although these expectations are partly founded on physiological facts about typical humans—such as having two legs with which to walk upright or having some capacity for sight or speech—their sociopolitical meanings and consequences are entirely culturally determined. Stairs, for example, create a functional “impairment” for wheelchair users that ramps do not. Printed information accommodates the sighted but “limits” blind persons. Deafness is not a disabling condition in a community that communicates by signing as well as speaking.3 People who cannot lift three hundred pounds are “able-bodied,” whereas those who cannot lift fifty pounds are “disabled.” Moreover, such culturally generated and perpetuated standards as “beauty,” “independence,” “fitness,” “competence,” and “normalcy” exclude and disable many human bodies while validating and affirming others. Even though the law attempts to define disability in terms of function, the meanings attached to physical form and appearance constitute “limits” for many people—as evidenced, for example, by “ugly laws,” some repealed as recently as 1974, that restricted visibly disabled people from public places.4 Thus, the ways that bodies interact with the socially engineered environment and conform to social expectations determine the varying degrees of disability or able-bodiedness, of extra-ordinariness or ordinariness.

Consequently, the meanings attributed to extraordinary bodies reside not in inherent physical flaws, but in social relationships in which one group is legitimated by possessing valued physical characteristics and maintains its ascendancy and its self-identity by systematically imposing the role of cultural or corporeal inferiority on others. Representation thus simultaneously buttresses an embodied version of normative identity and shapes a narrative of corporeal difference that excludes those whose bodies or behaviors do not conform. So by focusing on how representation creates the physically disabled figure in American culture, I will also clarify the corresponding figure of the normative American self so powerfully etched into our collective cultural consciousness. We will see that the disabled figure operates as the vividly embodied, stigmatized other whose social role is to symbolically free the privileged, idealized figure of the American self from the vagaries and vulnerabilities of embodiment.

One purpose of this book, then, is to probe the relations among social identities—valued and devalued—outlined by our accepted hierarchies of embodiment. Corporeal departures from dominant expectations never go uninterpreted or unpunished, and conformities are almost always rewarded. The narrative of deviance surrounding bodies considered different is paralleled by a narrative of universality surrounding bodies that correspond to notions of the ordinary or the superlative. Cultural dichotomies do their evaluative work: this body is inferior and that one is superior; this one is beautiful or perfect and that one is grotesque or ugly. In this economy of visual difference, those bodies deemed inferior become spectacles of otherness while the unmarked are sheltered in the neutral space of normalcy. Invested with meanings that far outstrip their biological bases, figures such as the cripple, the quadroon, the queer, the outsider, the whore are taxonomical, ideological products marked by socially determined stigmata, defined through representation, and excluded from social power and status. Thus, the cultural other and the cultural self operate together as opposing twin figures that legitimate a system of social, economic, and political empowerment justified by physiological differences.5

As I examine the disabled figure, I will also trouble the mutually constituting figure this study coins: the normate. This neologism names the veiled subject position of cultural self, the figure outlined by the array of deviant others whose marked bodies shore up the normate’s boundaries.6 The term normate usefully designates the social figure through which people can represent themselves as definitive human beings. Normate, then, is the constructed identity of those who, by way of the bodily configurations and cultural capital they assume, can step into a position of authority and wield the power it grants them. If one attempts to define the normate position by peeling away all the marked traits within the social order at this historical moment, what emerges is a very narrowly defined profile that describes only a minority of actual people. Erving Goffman, whose work I discuss in greater detail later, observes the logical conclusion of this phenomenon by noting wryly that there is “only one complete unblushing male in America: a young, married, white, urban, northern, heterosexual, Protestant father of college education, fully employed, of good complexion, weight and height, and a recent record in sports.”7 Interestingly, Goffman takes for granted that femaleness has no part in his sketch of a normative human being. Yet this image’s ubiquity, power, and value resonate clearly. One testimony to the power of the normate subject position is that people often try to fit its description in the same way that Cinderella’s stepsisters attempted to squeeze their feet into her glass slipper. Naming the figure of the normate is one conceptual strategy that will allow us to press our analyses beyond the simple dichotomies of male/female, white/black, straight/gay, or able-bodied/disabled so that we can examine the subtle interrelations among social identities that are anchored to physical differences.

The normate subject position emerges, however, only when we scrutinize the social processes and discourses that constitute physical and cultural otherness. Because figures of otherness are highly marked in power relations, even as they are marginalized, their cultural visibility as deviant obscures and neutralizes the normative figure that they legitimate. To analyze the operation of disability, it is essential then to theorize at length—as I do in part 1—about the processes and assumptions that produce both the normate and its discordant companion figures. However, I also want to complicate any simple dichotomy of self and other, normate and deviant, by centering part 2 of the book on how representations sometimes deploy disabled figures in complex, triangulated relationships or surprising alliances, and on how these representations can be both oppressive and liberating. In part 2, my examination of the way disability is constituted by the freak show, sentimental fiction, and black women’s liberatory novels focuses on female figures for two reasons: first, because the links between disability and gender otherness need investigating, and second, because the non-normate status accorded disability feminizes all disabled figures. What I uncover by closely analyzing these sites of representation suggests that disability functions as a multivalent trope, though it remains the mark of otherness. Although centering on disabled figures illuminates the processes that sort and rank physical differences into normal and abnormal, at the same time, these investigations suggest the possibility of potentially positive, complicating interpretations. In short, by examining disability as a reading of the body that is inflected by race, ethnicity, and gender, I hope to reveal possibilities for signification that go beyond a monologic interpretation of corporeal difference as deviance. Thus, by first theorizing disability and then examining several sites that construct it, I can uncover the complex ways that disability intersects with other social identities to produce the extraordinary and the ordinary figures who haunt us all.

The Disabled Figure in Literature

The discursive construct of the disabled figure, informed more by received attitudes than by people’s actual experience of disability, circulates in culture and finds a home within the conventions and codes of literary representation. As Paul Robinson notes, “the disabled, like all minorities, have … existed not as subjects of art, but merely as its occasions.” Disabled literary characters usually remain on the margins of fiction as uncomplicated figures or exotic aliens whose bodily configurations operate as spectacles, eliciting responses from other characters or producing rhetorical effects that depend on disability’s cultural resonance. Indeed, main characters almost never have physical disabilities. Even though mainstream critics have long discussed, for example, the implications of Twain’s Jim for blacks, when literary critics look at disabled characters, they often interpret them metaphorically or aesthetically, reading them without political awareness as conventional elements of the sentimental, romantic, Gothic, or grotesque traditions.8

The disparity between “disabled” as an attributed, decontextualizing identity and the perceptions and experiences of real people living with disabilities suggests that this figure of otherness emerges from positioning, interpreting, and conferring meaning upon bodies. Representation yields cultural identities and categories, the given paradigms Alfred Schutz calls “recipes,” with which we communally organize raw experience and routinize the world.9 Literary conventions even further mediate experience that the wider cultural matrix, including literature itself, has already informed. If we accept the convention that fiction has some mimetic relation to life, we grant it power to further shape our perceptions of the world, especially regarding situations about which we have little direct knowledge. Because disability is so strongly stigmatized and is countered by so few mitigating narratives, the literary traffic in metaphors often misrepresents or flattens the experience real people have of their own or others’ disabilities.

I therefore want to explicitly open up the gap between disabled people and their representations by exploring how disability operates in texts. The rhetorical effect of representing disability derives from social relations between people who assume the normate position and those who are assigned the disabled position. From folktales and classical myths to modern and postmodern “grotesques,” the disabled body is almost always a freakish spectacle presented by the mediating narrative voice. Most disabled characters are enveloped by the otherness that their disability signals in the text. Take, as a few examples, Dickens’s pathetic and romanticized Tiny Tim of A Christmas Carol, J. M. Barrie’s villainous Captain Hook from Peter Pan, Victor Hugo’s Gothic Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame, D. H. Lawrence’s impotent Clifford Chatterley in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and Tennessee Williams’s long-suffering Laura Wingfield from The Glass Menagerie. The very act of representing corporeal otherness places them in a frame that highlights their differences from ostensibly normate readers. Although such representations refer to actual social relations, they do not of course reproduce those relations with mimetic fullness. Characters are thus necessarily rendered by a few determining strokes that create an illusion of reality far short of the intricate, undifferentiated, and uninterpreted context in which real people exist. Like the freak shows that I will discuss in chapter 3, textual descriptions are overdetermined: they invest the traits, qualities, and behaviors of their characters with much rhetorical influence simply by omitting—and therefore erasing—other factors or traits that might mitigate or complicate the delineations. A disability functions only as visual difference that signals meanings. Consequently, literary texts necessarily make disabled characters into freaks, stripped of normalizing contexts and engulfed by a single stigmatic trait.

Not only is the relationship between text and world not exact, but representation also relies upon cultural assumptions to fill in missing details. All people construct interpretive schemata that make their worlds seem knowable and predictable, thus producing perceptual categories that may harden into stereotypes or caricatures when communally shared and culturally inculcated.10 As Aristotle suggests in the Poetics, literary representation depends more on probability—what people take to be accurate—than on reality. Caricatures and stereotypical portrayals that depend more ...

Table of contents

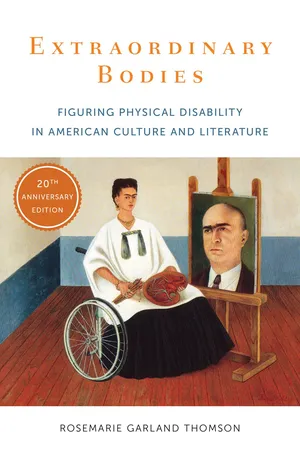

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to the Twentieth Anniversary Edition

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Part I: Politicizing Bodily Differences

- Part II: Constructing Disabled Figures: Cultural and Literary Sites

- Conclusion: From Pathology to Identity

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Illustrations