![]()

![]()

1

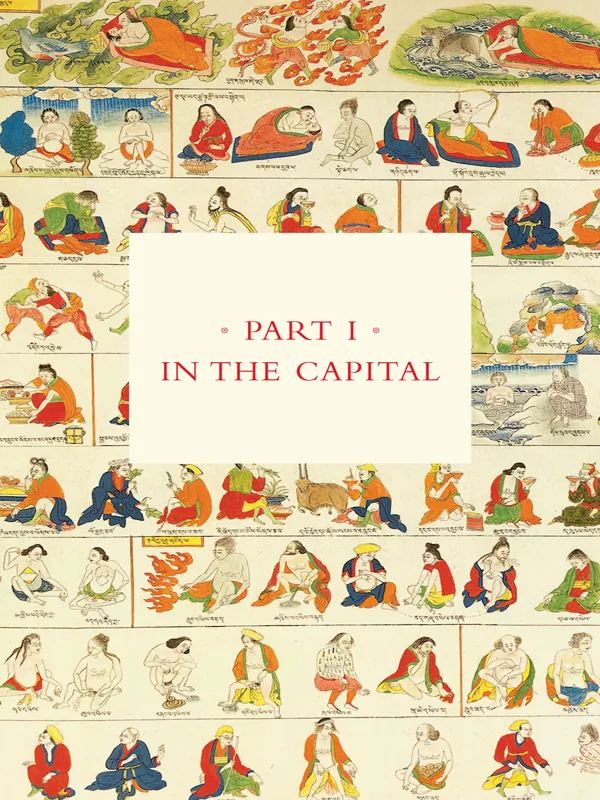

READING PAINTINGS, PAINTING THE MEDICAL, MEDICALIZING THE STATE

An extraordinary set of seventy-nine paintings, executed at the height of academic medicine in Tibet, serves well to launch this study.1 These exquisite tangka scrolls portray in meticulous detail the anatomy, materia medica, diagnostics, therapeutics, pathologies, and healthy and deleterious forces that determine the human condition. Their encyclopedic reach and generic depictions participate in trends, seen much more fully in other parts of the world during the same period, toward producing scientific illustrations from life. They are also stunning testimony to the artistic sophistication that could be mustered in the seventeenth-century Tibetan capital, and to the state’s investment in medical learning.

Beyond these paintings’ pedagogical value for medicine itself, they point to medicine’s import in other cultural arenas, especially for the new government of the Dalai Lamas. Their extraordinary range in content illustrates how medicine’s focus upon the quotidian realities of human life made it capable of rendering the scope of control to which the state itself aspired. This can also be discerned in the ways that the medical paintings represent religion, in turns exalting and critiquing it, but most notably subordinating it to larger conceptions of human flourishing, of which it represented but one part.

Endeavoring to “read” this artifact raises a host of methodological issues. Not the least is the problem of how to discern cultural significance in a field where knowledge about everyday life is still scanty. The challenge becomes all the more daunting when trying to read visual images, where broad cultural expertise is required to appreciate their manifold implicit messages. From art historian Francis Haskell to a semiologist of the likes of Roland Barthes, scholars have long recognized the difficulties and the risks of such an endeavor.2 In the present case, we are both helped and distracted by the fact that the images in question are closely tied to a textual corpus that they specifically represent: the massive four-volume commentary to the twelfth-century medical root text Four Treatises, written by Desi Sangyé Gyatso (1653–1705), chief minister and then regent of the Great Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Losang Gyatso (1617–82). The Desi also oversaw the production of the paintings. Indeed, a key question for this chapter concerns what was achieved by translating the Desi’s already comprehensive written commentary into visual form.

The puzzle of this redundancy also presents an opportunity. The ways that images say and do things that texts cannot—whether intentionally or not (as may be more faithfully the case)—has been a rich site of reflection in the semiology of art.3 What becomes visible when words are replaced by images? Much of my method in answering this question is based in comparison and attention to difference: between what the text says and the extra data added by the images; between the medical paintings and dominant modes of other Tibetan art, particularly religious icons and narrative illustration; and between the Desi’s stated aims for the set and the way its images point beyond them. These exercises help us to recognize the images’ distinctive modes of representation, as well as the cultural and even political connotations of the set taken as a whole.

It is still rare in the study either of Buddhism or Tibet to explore modes of representation for their larger cultural and historical implications. Sheldon Pollock’s magisterial reading of literary style in early modern South Asia is a recent exemplar of what is possible in a closely aligned field.4 There has also been more cross-disciplinary thinking in the art history of Buddhism, moving far beyond questions of dating and provenance. Patricia Berger’s study of the visual culture produced under the Qianlong emperor and its reflections of Qing imperial power is one excellent example.5 The following reflections have also benefited from the history of science for both Asia and Europe, which has taken anatomical and botanical illustration as a key site of signal trends in the conception of knowledge. For models further afield, one might look to the exceptional powers of imagination and interpretation in sociologist Norbert Elias’ reading of the drawings of the Medieval House-Book and what they reveal of the values, experiences, and atmosphere of the world of a medieval knight.6 Such exemplary work underlines the rich potential of imagery for historians. The Tibetan medical paintings certainly provide a fine case in point.

The study that follows is illustrated by images from a copy of the painting set that was made under the auspices of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama in the early twentieth century. In both content and aesthetics, this copy very closely replicates the original set, some of which is still preserved in Lhasa.7 The copy thus reliably mirrors the artistic and representational styles with which the paintings were first executed, and serves well as a basis for cultural and historical reflections.

PRECISION, PLAY, AND THE EVERYDAY

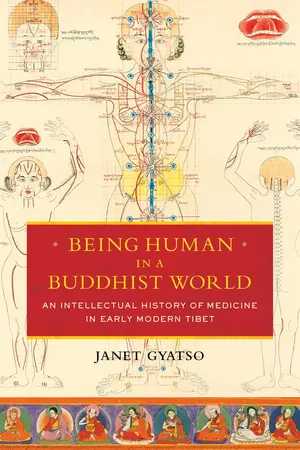

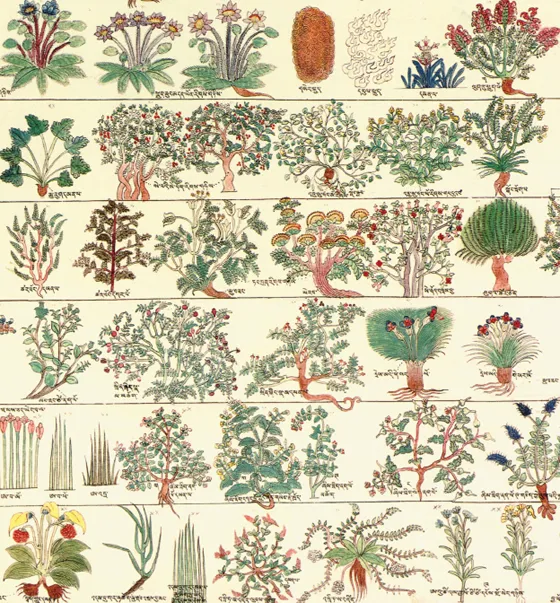

There is an immediate and palpable delight in looking at the medical paintings. One is struck at once by the beauty and vivid color of the large anatomical figures, as well as the pleasing order and neat rows of smaller vignettes. Each of the plates in the set evinces a sense of serene control and comprehensiveness. There is an exquisite precision and often intricate detail, even in the vignettes in their rows. Their individual distinctiveness is all the more striking for its contrast with these images’ commonality of position within the ordered parade of registers. The dynamic is well illustrated by an example from the medical botany (fig. 1.1).

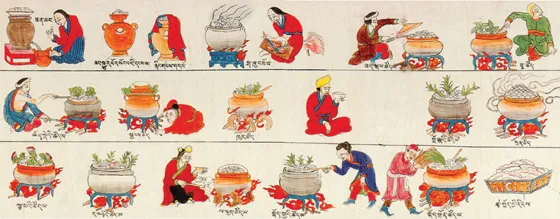

The artistry of the medical illustrations comes especially to the fore when their delightful details exceed their taxonomical import. This is determined by comparing the images with their corresponding description in the root text and the Desi’s Blue Beryl, summarized as well in captions on the plates themselves.8 A good example is a lively depiction of cooks in a series on types of prepared food (fig. 1.2). One cook samples the stew, one chops ingredients while the broth simmers, one checks under a lid, one bends down to adjust the fire, one keeps a spoon in the pot and another tool in the fire at the same time, one pours in more water, one looks away, seemingly distracted by something else. Note too the array of outfits and gender diversity. But none of these charming details has anything to do with the actual specifications of what is being denoted. The associated texts say nothing about the means to prepare the listed foods and certainly nothing about the people who do so.9 It appears rather that in rendering the taxonomical information of the texts, the artist also used the opportunity to depict an array of human types and familiar everyday scenes.

1.1 Medicinal plants in their ordered rows. Plate 26, detail

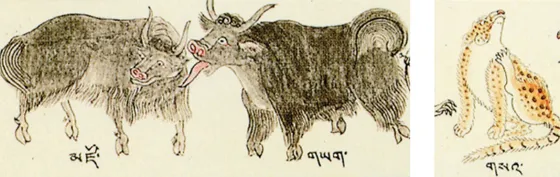

Imaginative extra detail can be found throughout the set. One good place to recognize it is in the section on categories of animals. They are not always pictured as mere passive creatures posing inertly for the zoology lesson. Rather, a number are shown doing something to amuse themselves or make themselves comfortable: a yak is licking his mate; a snow leopard is scratching itself under its neck; a cat is dozing (fig. 1.3).10

These animals are not taking their role in medical classification very seriously; in fact, they couldn’t care less. Yes, their shapes and coats serve to illustrate the features of the species they represent. But even if their postures of sleeping or expressing affection also show typical behavior for these species, these details have nothing to do with the medical text’s grounds for classification and are not mentioned in the text (nor is it terribly unique to leopards to scratch themselves or to yaks to lick their partners).11 Rather, these gestures make the animals seem real. We might say that representing both the taxonomical information and the larger life of animals serves to enhance the set’s credibility as an illustration of real objects in the world.12

In fact, much becomes visible when the details of depiction exceed overt didactic content. For now, note that the excess charm and delight have to do with everyday experience. This would be true for the artists, who would have drawn on such experience, as well as for the set’s viewers, larger parts of whose lives would inform their engagement with these images, beyond the business of medical learning itself.

Aside from extraneous detail, there is also a more fundamental respect in which everyday realities come to the fore. The set’s didactic content is itself about everyday human life. This fact is immediately striking to anyone with even the barest exposure to Tibetan art. The medical topics of these paintings set them apart from most illustrated scrolls produced in Tibet, predominantly religious in content. In contrast, the medical plates focus upon the ordinary material and social world and the ordinary people within it. In the course of portraying human anatomy, physiology, pathology, and pharmacology, the set pictures many, many scenes of quotidian life: people washing their hair, bathing in streams, giving each other massages, eating food, getting married. The predominance of such scenes and the relative infrequency of religious iconography in the set, with but a few exceptions, is remarkable.

A salient mark of the set’s unusuality are the many images of couples having sex, on practically every plate. We do of course see tantric yab yum deities in coitus and occasionally yogis doing sexual yoga in other Tibetan art, but very rarely everyday sex. The one notable exception is from the old Buddhist tradition of rendering the “wheel of life” (Skt. bhavacakra). Warning against the ills of samsara, such illustrations provide imagistic renderings of the “twelve interdependent links”: a person in the state of ignorance, a person being struck with the arrow of sensory perception, and so on, all shown to be in the clutches of the angry god of death, Yama (figure 1.4).13 Sometimes one or two links are represented as a couple having sex, symbolizing the sexual contact between man and woman that leads directly into ceaseless birth and death. In this eighteenth-century example, sex is portrayed twice in the outer rim, once elliptically at four o’clock, where the embracing couple represents “sensory contact,” and again at nine o’clock, where it is the clincher that makes for samsaric “existence” (figure 1.5).

1.2 People cooking various medicinal foods and brews. Plate 22, detail

1.3 Animals in the materia medica. Plate 21, details

But otherwise such images are very rare in Tibetan art.14 In contrast, the medical text speaks often of sex as one of the many kinds of human behavior that impact our health, and every time, it is duly represented on the painted plates as well. Figure 1.6 shows a few of the many examples in the set.

1.4 The Wheel of Life. Eastern Tibet; 18th...