![]()

I

BIRTH OF MODERN EVOLUTIONARY THEORY

![]()

1

THE ADVENT OF THE MODERN FAUNA

On the Births and Deaths of Species, 1801–1831

If evolution is the non-miraculous, scientific explanation for the origin of species, it will come as no surprise that the original problem that led to the development of evolutionary theory was the search for natural (secondary) causes to explain the origin of the modern biota: the living species of animals, plants, and fungi. It was a simple, hard-to-ignore fact that, as you climb vertical stacks of fossiliferous rocks, the fossils you find become progressively more modern in aspect, until, near the top of the sequence, in the youngest sediments, species still alive in the modern fauna begin to make their appearance.

Years ago, as a fledgling paleontologist, I used to wonder how it could possibly have been that, according to the historians of geology and biology I had read, early paleontologists and naturalists had evidently failed, if not to see, then at least to think seriously about, this pattern and what it might mean for an understanding of causal pathways leading to the advent of the modern fauna.

As it turns out, this general pattern of the progressive modernization of the fauna was indeed recognized by a diverse array of early natural philosophers, including some who remained opposed to the general idea of evolution (or at least Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s version of transmutation: Georges Cuvier, for example); others among the earliest to embrace transmutation (for instance, Robert Jameson); and the famous transmutational waffler (but skilled geologist and ecologist) Charles Lyell. As already noted, historians have tended to gloss over these early discussions of progressivism (or successionalism), trapped as most have been into thinking that evolution is fundamentally, perhaps even solely, a process of adaptive modification of organismal phenotypic characteristics.

THE OLD SHELL GAME

The fossil record of vertebrates has always held the most fascination for naturalist and layman alike, with the by-now dense fossil record of human evolution the secular equivalent of the Holy Grail. But it was the immensely denser, richer, and easier to find and to collect fossil remains of marine invertebrates in the younger sediments, typically distributed near the margins of continents, that led to the first empirical and analytical explorations of what might be the patterns and natural, non-miraculous causes underlying the appearance of new species, up to and including the advent of the modern fauna.

Earlier savants had advocated natural causal explanations for the history and diversity of life. Most famous, perhaps, was Charles Darwin’s own grandfather Erasmus Darwin, who deserves recognition in his own right, and not just for the more successful accomplishments of his grandson. But as grandson Charles was later to complain in Autobiography, Erasmus’s work was rather high on speculation and rather low on empirical evidence.

Systematics, the recognition and classification of natural groups of what came to be called “allied forms” by naturalists long before most of them subscribed to any notion of transmutation, was also a necessary, if not a sufficient, precursor to the emergence of what we would recognize today as modern evolutionary theory.

The Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and the Italian Giambattista Brocchi shared not only the same first name, but far more importantly, the distinction of being the first to develop natural causal explanations of the origins of modern species that were both empirically and phylogenetically based.

Both Lamarck and Brocchi attempted to trace lineages among closely similar species considered to be members of the same natural group, especially among species within a genus. They were applying a phylogenetic perspective to the search for causal explanations of the origin of modern species. Nor was this insistence on focusing the discourse on closely similar, apparently allied species necessarily a no-brainer. For example, Charles Lyell, in the second volume of Principles of Geology (1832), estimated that species originate, and become extinct, roughly at the rate of one per year, measured in all the ecosystems worldwide. But his gaze was thoroughly and steadfastly non-phylogenetic. Believing that, for example, a new species of carnivore could not appear until the proper prey species had appeared, Lyell’s notions of species origination and extinction were distinctly ecological, rather than phylogenetic, in character. Lyell’s book was largely an extended refutation of Lamarck’s ideas, and against the very idea of transmutation, though he did pirouette on the fence in one long paragraph, in which he acknowledged the pattern of the progressive “younging” of species as one approaches modern times in the fossil record.

Both Lamarck and Brocchi developed their earliest ideas through studies on Cenozoic (roughly 65 million years ago down to the youngest sediments) fossil mollusks. The advent of the modern fauna, as seen especially as the replacement of species within genera in marine mollusks, was the crucible in which the rudiments of evolutionary theory were born. And from its very inception, evolutionary process theory was divided into two camps, based on strikingly different claims on the very nature of patterns of stability and change of species in the fossil record: Lamarck and Brocchi made radically different claims about empirical patterns they saw revealed by their fossils.

Lamarck saw utter continuity and intergradation in time and space: all species are destined to change slowly into descendants through time, and, when the data were complete, would also be seen to intergrade geographically into other species of the same genus.

In sharp contrast, Brocchi regarded species as discrete and stable entities. Species have births, histories with little or no change, and eventually, inevitably, deaths programmed into them like the deaths of individual organisms. Old species do not change into descendants. Rather, they give birth to new, descendant species, just as organisms give birth to offspring.

It is one of the greatest ironies in the history of biology that Darwin, so often seen as the polar opposite of Lamarck in terms of the mechanisms they put forward to explain transmutation (natural selection versus the “inheritance of acquired characters”), came to insist that Lamarck was right when it comes to the patterns of evolution: species are bound to change through time, intergrading imperceptibly into descendants. While the fossil record seems to say the opposite, Darwin decided that the fossil record itself was at fault. That species do not seem to intergrade laterally, he decided, was that intermediate populations, subspecies, and closely related species had succumbed to extinction. The pattern of evolution Darwin left us with was Lamarckian—though his initial scientific thinking in evolution was pure Brocchian transmutation.

In the terminology I used in the late 1970s, then, Lamarck was thinking “transformationally,” while Brocchi was thinking “taxically.” The dichotomy was there from the inception. What follows is a bit more detail on Lamarck’s and Brocchi’s seminal views, and the critical demonstration that young Darwin was thoroughly familiar with both sets of ideas through his training in the 1820s—especially as a medical student in Edinburgh from 1825 to 1827, but also through his experiences at Cambridge in the years leading up to the Beagle voyage.

LAMARCKIAN TRANSMUTATION

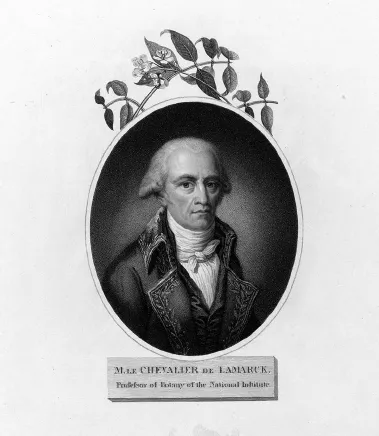

Containing the earliest significant arguments proposing transmutation based on perceived temporal sequences of closely related species, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck’s writings in the early nineteenth century stand firm as the earliest empirical, transmutational scientific work critical to the emergence of evolutionary biology as we know it today (figure 1.1). And though Lamarck is perhaps best remembered for the evolutionary ideas expressed in Philosophie zoologique (1809), his first important statements on the subject appear in the short introductory section on fossil mollusks in Systême des animaux sans vertèbres (1801:403–411).

As becomes clear as we trace the influence of both Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Giambattista Brocchi, primarily if not solely among the medically trained savants in Edinburgh in the 1810s and 1820s, both Lamarck’s admirers and his detractors often mocked him for his exaggerated claims—not over process, but instead over his actual, putatively empirical, claims about the patterns of biological history he claimed to be generally true.

FIGURE 1.1 James Hopwood Sr., Jean-Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet, Chevalier de Lamarck. (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

Consider, for example, the words of Charles Lyell in the opening page of volume 2 of Principles of Geology. Lyell equated transmutation strictly with Lamarck. (Later in the book, however, Lyell also discusses Brocchi by name. Lyell was virtually the only person to do so, save his own father-in-law.) Framing the problem of transmutation in explicitly empirical terms, Lyell ([1832] 1997) challenged his reader to “inquire, first, whether species have a real and permanent existence in nature; or whether they are capable, as some naturalists pretend, of being indefinitely modified in the course of a long series of generations” (183).

Lyell is sneering at what he goes on to characterize as Lamarck’s blatantly absurd claim about the pattern of transmutation. I cite this passage here, anachronistically, simply because it so well typifies the way many natural philosophers felt about species. Whether creationists (like philosopher William Whewell) or those otherwise disposed toward the search for natural causal explanations of the origins of modern species (such as geologist Robert Jameson), pretty much everybody acknowledged the reality and apparent stability of species. What did Lamarck really say?

Lamarck was hired in 1793 to be in charge of invertebrates (animaux sans vertèbres) at the Natural History Museum (Jardin des Plantes) in Paris. It was not uncommon in these early days of natural history for appointments to be made to positions for which the nominee had no particular training or expertise: Charles Darwin’s mentor at Cambridge, John Stevens Henslow, was already Professor of Mineralogy when he was named Professor of Botany in 1825, reflecting his growing interest in the subject. Henslow duly turned himself into a thorough-going botanist. Adam Sedgwick, who was similarly appointed Professor of Geology at Cambridge without any real track record in the subject, quickly became a leading geologist of his time. And so it was, two decades earlier, that Lamarck, taking his appointment seriously, set out to study invertebrate organisms, publishing Systême des animaux sans vertèbres in Paris in 1801, or in “the eighth year of the Republic.” Historian Janet Browne (1995) reports that Darwin read Lamarck’s work on invertebrates while in medical school in the mid-1820s, and would have read the “text of his lecture” (83) on animal change through time.

It is in the introduction to the section “On Fossils” that Lamarck launches into a discussion of what fossils are and why they are interesting. On their own, he says, fossils, typically having lost their original color, have next to no intrinsic interest. But when fossils are seen as “extremely precious monuments” for the study of “revolutions” to which different places on the earth’s surface have been subjected—and the study as well of the “changes that living beings have successively experienced there”—they become of the “highest interest” to naturalists (Lamarck 1801:406).

Lamarck (1801:407) goes on to say that several naturalists (evidently thinking especially of his colleague Georges Cuvier) have claimed that all fossils belong to the remains of animals or vegetables for which there are no living analogues. Cuvier was even then promoting his ideas of “revolutions” on the surface of the globe, the forerunner to modern discussions of mass extinction events. Cuvier was specifically concerned with proving that many species of large fossil mammals, such as the South American Megatherium, were not only extinct, but had no particularly close living relatives.

Not so, says Lamarck, for such naturalists “want to explain everything,” and don’t take the trouble to study the course that nature takes. And here Lamarck (1801:408) begins to walk an interesting tightrope—saying that in fact a small number of fossil species do have living analogues. And besides, among the fossil species without apparent living analogues, many belong to the same genera as are found in the modern oceans, differing more or less from their fossil relatives to the point at which they cannot be considered the same species.

The explanation of why only a few fossil species seem to be the same as living species, Lamarck tells us, is that most fossil species have changed in the course of time. He goes on to say that nothing is constant on the face of the earth, and “diverse mutations” occur, prompted by the “nature of objects and circumstances.” Environmental change prompts changes in “situation, form, nature and appearance,” and a diversity of habitats, a “different way of existing,” followed by “modifications or developments in their organs and in the form of their parts,” such that “every living being must vary insensibly in its organisation and form.” The changes are propagated “through generation [reproduction], and after a long chain of centuries, not only will new species, new genera and even new orders appear, but every species will necessarily be varied in its organization and forms.”

So Lamarck concludes that what is astonishing is not that so few fossil species have living analogues, but that there are any living species at all that are also known from the fossil record. And most of the relatively few fossil species with living analogues still extant must be among the youngest fossils known, for they simply have not had the time to change.

So one cannot really conclude, Lamarck says, that fossil species with no exact living analogues are in fact extinct. Humans may have driven some of the large fossil mammals to extinction, but this is not a matter that can be decided from the fossil record alone, as there are many regions on earth yet to be fully explored.

Hence Lamarck’s tightrope: he wants to deny extinction, but has to admit that relatively few fossil species seem to be identical to still-living counterparts. He argues against external causation for extinction, arguing instead for a form of extinction-through-transmutation: the inevitable and insensible changes in form of species as the ages roll virtually ensures that no living species will be found to be exactly the same as its fossil counterparts. Though he and Cuvier actually agree that many fossil species have no evident exact living counterparts, Lamarck disagrees strongly with Cuvier on why this is so.

In 1809, Lamarck published Philosophie zoologique, easily the better known exposition of his transmutational views. Lamarck’s words leave no doubt that Lyell, Darwin, and others who read him were correct to say that Lamarck saw the organic world in a constant state of flux within phylogenetic lineages, with constant, gradual change from one species to another through time, as well as in space. For example, Lamarck ([1809] 1984) wrote: “Let me repeat that the richer our collections grow, the more proofs do we find that everything is more or less merged into everything else, that noticeable differences disappear, and that nature usually leaves us nothing but minute, nay puerile, details on which to found our distinctions” (37).

Lamarck’s notion entailed the destruction of the creationist view that species are inherently stable, discrete, forever unchanging, and are unconnected to any other species. The alternative view developed by Brocchi and adopted by a number of naturalists was that species are indeed real, and discrete, but are connected in phylogenetic series through a process of birth of descendant species from older ones. And unlike Lamarck, Brocchi and like-minded naturalists were perfectly willing to concede that species die—become extinct—through natural causes, though they disagreed on what those causes may be. And even a few (like Jameson) entertained a sort of mixture of Lamarckian and Brocchian views.

One final note on Jean-Baptiste Lamarck before moving on to Giambattista Brocchi. Lamarck died in 1829. He was eulogized by his longtime adversarial colleague Georges Cuvier (1836). The eulogy (“elegy”) appeared in English translation in Jameson’s Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, most likely translated by Jameson himself. The standard interpretation...