![]()

Thomas Anderson

Thomas Anderson has been living two lives. During the day, he works a mind-numbing job as a computer geek for a software company. At night, he hacks systems as Neo. He is the intense guy who can get anything for anyone for a price. Then, messages start to come through the computer from a mysterious entity named Morpheus. Bits and pieces of sentences. A word or two. Neo is perplexed. Confused. Driven to paranoia. One morning, exhausted, he sees these words fixed across his screen: “Wake up, Neo . . . the Matrix has you.”

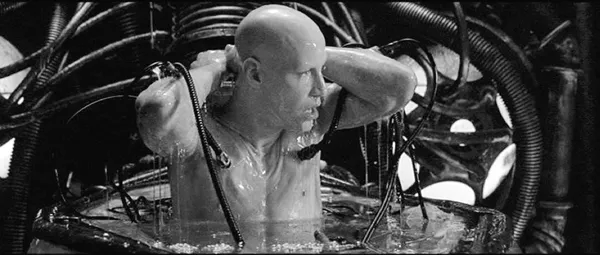

What is the Matrix that Neo discovers in the Wachowski brothers’ science fiction film? In a horrifying scene of human beings trapped in metallic pods perched along an immense beehive structure, Neo learns that the Matrix is a computer program in which humans live their lives. It is a virtual reality created by intelligent machines to control humans. The machines incubate and grow humans to extract from their bodies the energy that the machines need to survive (figure 1.1).

To keep humans passive, the machines wire them into the Matrix, where they happily live out virtual lives on twentieth-century Earth while encased in goo in a pod, with extraction wires bored into their bodies. The Matrix is the humans’ only reality. It is what gives their lives purpose and meaning. Asleep like babies, they never know that they are living out their lives from the perspective of the Matrix, which is nothing more than a software program they are wired into.

Figure 1.1 Thomas Anderson (Keanu Reeves) emerges from his pod in The Matrix (1999).

It is unnerving to think of our reality as a constructed matrix, a software program that we are wired into. Although we are not humans incubated in pods by machines, we inhabit a worldview that has been constructed for us by our human ancestors, and we perceive this worldview to be reality, the way things actually are. Yet, when we study the flux of history and cultures, we see very plainly that worldviews are adjustable and what is viewed as “real” changes with time and location. Humans are known for shifting and altering the worldviews or matrices that structure and organize people’s lives, including people’s spiritual orientation, what we call today “spirituality.”

Spirituality points to the metaphysical orientation that directs our lives. It is like our sexual orientation, only in reference to our views of the existential and transcendent. It is our view of reality. It is the metaphysical matrix that we live within. It is like the Wachowskis’ vision of a human software program that we engage when we think about all there is and how we fit in. It involves how we structure our lives around the big questions of existence, reality, transcendence, and the sacred (cf. Fuller 2001, 8–9; Sheldrake 2007, 1–2; Kaufman 1993, 45–47). What exists ultimately? Who are we fundamentally? What do we value deeply? Why are we here primarily? What inspires us with awe and dread? Our answers to these types of questions create the spiritual matrix in which we orient ourselves, enabling us to lead structured and meaningful lives within a chaotic world where suffering and death are unavoidable.

How then does religion fit into this? If spirituality is how we meaningfully orient our lives to the existential, to the transcendent and to the sacred, then what is religion? Religion is the communal or collective expression of this metaphysical orientation through symbol, language, and behavior. Religion is the organized community of worship, the fellowship of the faithful.

Spirituality and religion are intimately linked. It is the spirituality of a people, their orientation toward the existential, transcendent, and sacred, that generates an organized religion in which the people can come together in community. The religion serves as the institutional platform, reinforcing the spirituality that originally generated the religion.

But what happens when a new way of perceiving reality forms in a community, when the traditional spiritual orientation that has maintained a religion goes offline? There is a software shift, so to speak, or as in Neo’s case, a matrix rift, when he takes the red pill and experiences another reality altogether. It is a rift that causes religious dissociation. To deal with this matrix rift, some people attempt to realign their religion’s older spirituality with their new perspective by reforming the religion. If this fails, they turn away and become “unchurched,” as in the spiritual-but-not-religious New Age mindset today (Fuller 2001).

This type of rift between an old spirituality that grounds a traditional organized religion and a newly developed spirituality is not novel to the contemporary American religious scene. It is something that ancient people in the Mediterranean experienced at the beginning of the first century CE when Gnostic spirituality came online and challenged the very foundations of the religions of the time. It is a spirituality that revolutionized religion so that it could focus on the quest of the individual human for wholeness rather than on the perpetual quest, motivated by fear, to satisfy the gods and their desires through submission and obedience. It is a radical orientation that remains in play in modern American religion, where its once heretical message about the power of the divine human has become mainstream. Its therapeutic message of self-transfiguration has become America’s favored form of spirituality, successfully confronting older models of spirituality that have been in play since antiquity.

What types of spirituality were common in antiquity before the emergence of this Gnostic orientation? What worldviews were the Gnostics overturning? There were three main types of spirituality that dominated the religious scene before the emergence of the Gnostic orientation: servant, covenant, and ecstatic spirituality. These types of spirituality generated the religions around the Mediterranean and, like the turning of a wheel, were themselves nurtured and maintained by the organized religions.

Servant Spirituality

The oldest spirituality in the Mediterranean basin is servant spirituality. This is the metaphysical orientation that fostered all of the religions in the ancient Mediterranean. This metaphysical orientation views the human being as a mortal creature crafted by a more powerful being or god who is immortal. As the god’s creature, the human being is the god’s property to do with as the god wishes, even arbitrarily. Gods in these systems typically act as humans might, with emotions and passions that result in capricious and indiscriminate behavior on their part. The sole purpose for the creation of the human being is to produce an entity that will relieve the gods of toil. The human is created to serve the gods, not out of love or respect but out of obligation and fear. If the gods are pleased with the service, the humans may not be punished or destroyed. If the gods are displeased, then famine, pestilence, or war could consume them.

Integral to servant spirituality is the belief that the natural tendency of our world, including human inclinations and affairs, is to disintegrate into chaos. This propensity has to be overcome and the world brought into order and then forever maintained. Since human inclination is predisposed to chaos, structure must be managed externally. This begins with the gods, who establish order primordially, slaying or imprisoning the draconian forces of chaos, structuring the architecture of the heavens and the earth, and setting time in motion.

The intent of the gods is to organize a world that is stable and peaceful so that it will support their own desired lifestyle of leisure. The problem is that the natural drift of the world toward chaos remains. The primordial structure cannot sustain itself. If let go, it would naturally disintegrate into chaos.

How could this problem be solved? The onerous job of maintaining cosmic stability and peace fell to humans under the direction of a leader or king who was believed to operate in the best interests of the gods, either as their representative or as their son.

One of the primary tasks of the king is to interpret and enforce the will of the gods in order to keep the gods content and sympathetic toward his community. To this end, the king must make sure that human beings build temples to house the gods and to care for them. He must ensure that human beings perform the religious rituals that satisfy the gods with worship and gifts. Since the gods desire that the cyclic structure of creation and nature be sustained as they had established it originally, the king must make certain that human beings regularly imitate or duplicate the establishment of primordial order on the microcosmic, ritual level. All of this results in governance based upon iterative or repetitive actions of the king and his subjects, which maintain the traditional state rather than innovate or develop it in any progressive way.

The king’s other job is to maintain civil order among humans whose natural state of avarice parallels the proverbial observation that the big fish will always eat the little fish. The king is expected by the gods to uphold justice within his community so that the weak are protected against the strong and the poor against the rich. It becomes the job of the king, then, to suppress the barbaric and greedy nature of the human being through strong, even oppressive, governance.

The classic metaphysical orientation that conceives of powerful immortal deities who harness chaos and create mortal human beings to sustain cosmic order has its consequences. It results in a picture of the human as a forced laborer who toils beneath the weight of maintaining the will of the gods and their creation, endlessly in servitude to the gods and their king (cf. Assmann 1989, 55–88; Moscati 1960). And to what end? The afterlife provided no relief. As a shadow, the deceased endured in gloom and wretchedness, eating dust and drinking dirty water. The only hope for respite came from the living, who might provide the dead with grave offerings of food and wine. If the living forgot to assist them, however, the shades would wander restlessly on the earth and molest the living as malicious demons.

Life and Death in Babylonia

Servant spirituality was at the heart of the Babylonian religion, as can be seen in the Babylonian creation story Enuma Elish, in which human beings are viewed as the pinnacle of creation but not as a stunning climax (Jacobsen 1976, 167–91). They are an afterthought molded to serve the pantheon of gods in the temples of Marduk. By imposing upon humans the task of serving the gods, the ancient myth reasons, the gods are set free to do as they please.

The inferiority of humans is accentuated by the Babylonian tale when it relates that humans were created from a mixture of earth and the blood of the conquered primordial demon of chaos, Kingu (Enuma Elish 4.33–34). In this yarn, it is something of a pitiful joke that human beings are perceived to be the combination of dust and the blood of the one of the oldest monsters of chaos in Babylonian mythology. To put it another way, the tendency toward anarchy, the blood of chaos, runs in our veins.

The Babylonians understood their enforcement of civil law, such as the famous Code of Hammurabi, to be necessary to maintain control over the chaos that is in the blood of all humans. Legend records that King Hammurabi was appointed by the gods Anu and Enlil to make justice rule in the land and to destroy the wicked and the unjust so that the strong would not oppress the weak. To promote justice and communal well-being, he received laws from these gods, which he was appointed to enforce. As the representative of their laws, he possessed absolute sovereignty to do so.

After a lifetime of forced servitude to god and king came death, when the Babylonians thought that the deceased would be transformed into an etimmu (ghost). This entity is an insubstantial shade of the deceased that resides underground in the land of no return. As the classic Epic of Gilgamesh maintains, every human being dies, including the greatest of heroes, and goes to the land of the dead to eat dust as food and to dwell in darkness. This is the wretched fate of every one of us, good or bad. Gilgamesh laments (Jacobsen 1976, 207):

What can I do, Utanapishtim, where will I go?

The one who followed behind me,

the rapacious one,

sits in my bedroom, Death!

And wherever I may turn my face,

there he is, Death!

So what was the point? The righteous suffer—of this the Babylonians were keenly aware. Even when they fulfilled all their tasks as servants of the gods, still they suffered under their heavy burden. Who is to know, they concluded, what the gods really desire? Humans are mere mortals. “He who was alive yesterday is dead today,” they said. “What is evil to a person’s mind is good for a god” (Pritchard 1969, 435).

Submission for Eternity in Egypt

Servant spirituality structured the Egyptian religion, too, where the human being is so marginal that the mythology does not bother to mention the creation of humans, or does so only in passing, as creatures that emerged from the unintentional tears of Atum (Lloyd 1989). Atum is the primary self-generated god, the first to come out of the primordial darkness. He is relieved when his brother and sister return to him after leaving him alone for a time. It is from the tears of relief he sheds at his reunion with them that human beings spring, unplanned. In one such mention, it is remarked that the tears were wept out of anger, suggesting that the human race is a product of Atum’s rage and misery (Faulkner 2004, spell 714). In another version of the story, it is tears of sorrow and loneliness that produce human beings, suggesting that the human race is a product most sorrowful and pitiful (spell 1130).

In some accounts, humans are molded from mud or clay by the creator god Khnum, who makes them on his potter’s wheel, continually producing bodies of children yet to be born. At their births, the ka (life breath) is breathed into them. Death occurs when the ka departs from the body to take up residence in a statue or portrait of the person in the tomb. It is difficult to render fully the meaning of ka into English because we have no similar concept today. It is considered to be the person’s vitality and so is rendered as a twin or double of the individual.

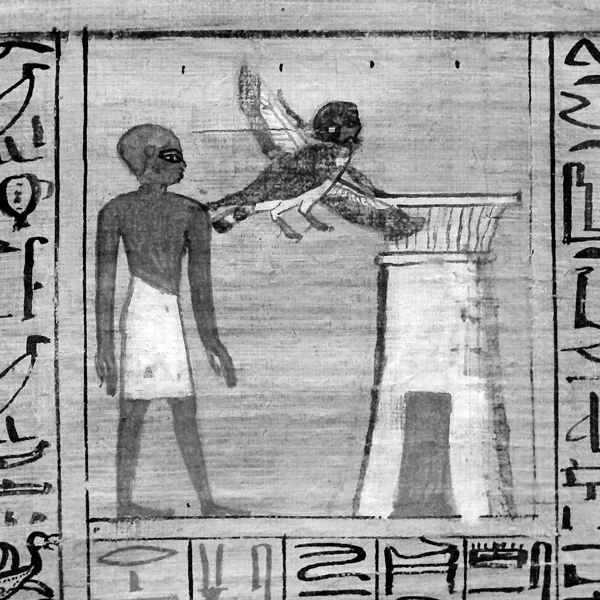

In addition, the human being has a ba, an individual capacity to move. It assumes immense importance after death, when the corpse can’t move, and it must be released from the body through a ritual called the Opening of the Mouth. The ba is depicted as a bird or animal manifestation of the person, which can leave the tomb and roam the earth and sky during the day, returning to the underworld every night to be reunited with the ka (figure 1.2).

Once the person had been properly mummified, the unification of the ka and ba resulted in the separation of the akh from the corpse. The akh is the glorified afterlife form of the person, the deceased reconstituted as a being of light. The akh was like a roaming ghost.

Figure 1.2 Illustration of the ba leaving the deceased, from a version of the Book of the Dead displayed in the Museo Egizio, Turin, Italy. Photo courtesy of April D. DeConick.

Why are humans around, according to the ancient Egyptians? Their job is to maintain maat (truth, justice, and order), which was established by the gods when primal chaos...