![]()

1

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ACADEMIC FREEDOM

GEOFFREY R. STONE

AS COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY professor and former provost Jonathan R. Cole observed in his work The Great American University, “the protection of ideas and expression from external political interference or repression became absolutely fundamental to the university.”1 Indeed, it is in no small measure our deep commitment to academic freedom that has allowed American universities to be “great.”

It is imperative, though, that we never take academic freedom for granted, for the freedom of thought and inquiry we enjoy today in the academy is the product of centuries of struggle, and in the first part of this essay I will briefly trace the history of academic freedom, because unless we know how we got to where we are today we may not understand just how unique and potentially fragile our academic freedom really is. In the final part of this essay, I will offer a few thoughts about the challenges of the future.

Although the struggle for academic freedom can be traced at least as far back as Socrates’s eloquent defense of himself against the charge that he corrupted the youth of Athens, the modern history of this struggle, as it has played out in the university context, begins with the advent of universities, as we know them today, in the twelfth century.

In the social structure of the Middle Ages, universities were centers of power and prestige. They were largely autonomous institutions, conceived in the spirit of the guilds. Their members—whom we today would describe as their faculty—elected their own officials and set their own rules.

There were, however, sharp limits on the scope of scholarly inquiry. There existed a hard core of authoritatively established doctrine that was made obligatory on all scholars and teachers. It was expected that each new accretion of knowledge would be consistent with a single system of truth, anchored in Christian dogma.

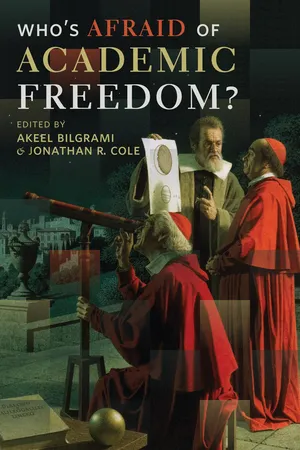

As scholars and teachers gradually became more interested in science and began to question some of the fundamental precepts of religious doctrine, the conflict between scientific inquiry and religious authority grew intense. When Galileo published his heretical telescopic observations, for example, he was listed as a suspect in the secret books of the Inquisition, threatened with torture, compelled publicly to disavow his views, and imprisoned for the remainder of his life.

Throughout the seventeenth century, university life remained largely bounded by the medieval curriculum. Real freedom of thought was neither practiced nor professed. As one statement of the then prevailing ideal put the point, the teacher was “not to permit any novel opinions to be taught,” nor was he to teach “anything contrary to prevalent opinions.”2

This was the general attitude in America, as well as in Europe, and freedom of inquiry in America was severely limited by the constraints of religious doctrine until well into the nineteenth century. In 1654, for example, Harvard’s president was forced to resign because he denied the scriptural validity of infant baptism.

The latter part of the eighteenth century saw a brief period of relative secularization of the American college as part of the Enlightenment. By opening up new fields of study and by introducing a note of skepticism and inquiry, the trend toward secular learning began gradually to liberate college work. The teacher of science introduced for the first time the discovery, rather than the mere transmission, of knowledge into the classroom.

This shift was short-lived, however, for the opening decades of the nineteenth century brought a significant retrogression. This was due largely to the rise of religious fundamentalism in the early years of the nineteenth century, which led to a sharp counterattack against the skepticism of the Enlightenment and a concerted effort on the part of the Protestant churches to reassert their control over intellectual life.

As a result of this development, the American college in the first half of the nineteenth century once again found itself deeply centered in tradition. It looked to antiquity for the tools of thought and to Christianity for the laws of living. It was highly paternalistic and authoritarian. Its emphasis on traditional subjects, mechanical drill, and rigid discipline stymied free discussion and squelched creativity.

Three factors in particular stifled academic freedom in this era. First, the college teacher was regarded first and foremost as a teacher. Because academic honors hinged entirely on teaching, there was no incentive or time for research. Indeed, it was generally agreed that research was positively harmful to teaching. In 1857, for example, the trustees of Columbia College attributed the low state of the college to the fact that some of its professors “wrote books.”

Second, educators of this era generally regarded the college student as intellectually naive and morally deficient. “Stamping in,” with all that phrase implies, was the predominant pedagogical method, and learning was understood to mean little more than memorization and repetitive, mechanical drill.

Third, freedom of inquiry and teaching was smothered by the prevailing theory of “doctrinal moralism,” which assumed that the worth of an idea should be judged by its moral advantages, an attitude that is anathema to scholarly inquiry.

The most important moral problem in America in the first half of the nineteenth century was, of course, slavery. In both the North and the South, colleges rigidly enforced their views on this subject. By the 1830s, the mind of the South had closed on this issue. When it became known, for example, that a professor at the University of North Carolina was sympathetic to the 1856 Republican presidential candidate, the faculty repudiated his views, the students burned him in effigy, and he was discharged by the trustees. The situation in the North was not much better. The president of Franklin College was dismissed because he was not an abolitionist, and Judge Edward Loring was dismissed from a lectureship at the Harvard Law School because, in his capacity as a federal judge, he had enforced the fugitive slave law.

Between 1870 and 1900, there was a genuine revolution in American higher education. Dramatic reforms, such as graduate instruction and scientific courses, were implemented, and great new universities were established at Cornell, Johns Hopkins, Stanford, and Chicago. New academic goals were embraced. To criticize and augment, as well as to preserve the tradition, became an accepted function of higher education. This was an extraordinary departure for a system that previously had aimed primarily at cultural conservation. Two forces in particular hastened this shift. The first was the impact of Darwinism. The second was the influence of the German university.

By the early 1870s, Darwin’s theory of evolution was no longer a disputed hypothesis within the American scientific community. But as scientific doubts subsided, religious opposition rose. Determined efforts were made exclude proponents of Darwinism whenever possible. The disputes were often quite bitter.

This conflict brought together like-minded teachers, scientists, scholars, and philosophers who believed in evolution and who developed new standards of academic inquiry. In their view, to dissent was not to obstruct, but to enlighten.

The great debate over Darwinism went far beyond the substantive problem of whether evolution was true. It represented a profound clash between conflicting cultures, intellectual styles, and academic values. It pitted the clerical against the scientific; the sectarian against the secular; the authoritarian against the empiricist; and the doctrinalist against the naturalist. In these conflicts, science and education joined forces to attack both the principle of doctrinal moralism and the authority of the clergy.

A new approach to education and intellectual discourse grew out of the Darwinian debate. To the evolutionists, all beliefs were tentative and verifiable only through a continuous process of inquiry. The evolutionists held that every claim to truth must submit to open verification; that the process of verification must follow certain rules; and that this process is best understood by those who qualify as experts.

In the attack upon clerical control of universities, the most effective weapon was the contention that the clergy were simply incompetent in science. The result of this attack was the almost complete disappearance of the clergy as a serious academic force. In 1860, 39 percent of the members of the boards of private colleges were clergymen; by 1900, the percentage had dropped to 23 percent; by 1930, it had dwindled to 7 percent.

The other factor that played a critical role in the transformation of American higher education in the late nineteenth century was the influence of the German university. The modern conception of a university as a research institution was in large part a German contribution.

The object of the German university was the determined, methodical, and independent search for truth. Such a vision of the research university attracted individuals of outstanding abilities, rather than mere pedagogues and disciplinarians. The German professor enjoyed freedom of teaching and freedom of inquiry. The German system held that this freedom was the distinctive prerogative of the academic profession and that it was the essential condition of a university.

Indeed, the single greatest contribution of the German university to the American conception of academic freedom was the assumption that academic freedom defined the true university. As William Rainey Harper, the first president of the University of Chicago, observed in 1892: “When for any reason … the administration of [a university] attempts to dislodge a professor because of his political or religious sentiments, at that moment the institution has ceased to be a university.”3

Although American universities borrowed heavily from the German in this era, there evolved two critical differences between the American and German conceptions of academic freedom. First, whereas the German conception encouraged the professor to convince his students of the wisdom of his own views, the American conception held that the proper stance for professors in the classroom was one of neutrality on controversial issues. As President Charles Eliot of Harvard declared at the time: “The notion that education consists in the authoritative inculcation of what the teacher deems true … is intolerable in a university.”4

Second, the German conception of academic freedom distinguished sharply between freedom within and freedom outside the university. Within the walls of the academy, the German conception allowed a wide latitude of utterance. But outside the university, the German view assumed that professors were obliged to be circumspect and nonpolitical.

American professors rejected this limitation. Drawing upon the more general American conception of freedom of speech, they insisted on participating actively in the arena of social and political action. American professors demanded the right to express their opinions even outside the walls of academia, even on controversial subjects, and even on matters outside their scholarly competence.

This view of academic freedom has generated considerable friction, for by claiming that professors should be immune not only for what they say in the classroom and in their research but also for what they say in public debate, this expanded conception empowers professors to engage in outside activities that can inflict serious harm on their universities in the form of disgruntled trustees, alienated alumni, and disaffected donors.

These issues were brought to a head in the closing years of the nineteenth century, when businessmen who had accumulated vast industrial wealth began to support universities on an unprecedented scale. For at the same time that trusteeship in a prestigious university was increasingly becoming an important symbol of business prominence, a growing concern among scholars about the excesses of commerce and industry generated new forms of research, particularly in the social sciences, that were often sharply critical of the means by which these trustee-philanthropists had amassed their wealth.

The moguls and the scholars thus came into direct conflict in the final years of the nineteenth century. For example, a professor was dismissed from Cornell for a pro-labor speech that annoyed a powerful benefactor, and a prominent scholar at Stanford was dismissed for annoying donors with his views on the silver and immigration issues. This tension continued until the beginning of World War I, when it was dwarfed by an even larger conflict.

During the Great War, patriotic zealots persecuted and even prosecuted those who questioned the war or the draft. Universities faced the almost total collapse of the institutional safeguards that had evolved up to that point to protect academic freedom, for nothing in their prior experience had prepared them to deal with the issue of loyalty at a time of national emergency.

At the University of Nebraska, for example, three professors were discharged because they had “assumed an attitude calculated to encourage … a spirit of [indifference] towards [the] war.”5 At the University of Virginia, a professor was discharged because he had made a speech predicting the war would not make the world safe for democracy. And at Columbia, the board of trustees launched a general campaign of investigation to determine whether doctrines that tended to encourage a spirit of disloyalty were being taught at the university.

Similar issues arose again, with a vengeance, during the age of McCarthy. In the late 1940s and 1950s, many if not most universities excluded those accused of Communist sympathies from participation in university life. The University of Washington fired three tenured professors, the University of California dismissed thirty-one professors who refused to sign an anti-Communist oath, and Yale president Charles Seymour boasted that “there will be no witch hunts at Yale, because there will be no witches. We will not hire Communists.”6 At many universities, fac...