![]()

1

Long-Distance Realism

Agnes Smedley and the Transpacific Cultural Front

In the 1920s The Pacific buzzed and hummed with chatter. The recent laying of the first transpacific cable line made individuals on both sides of the ocean eager to communicate, gossip, and spread ideas. A sea of electrified language linked Shanghai to San Francisco and New York City. By the early 1930s that humming of language took on a particular, surprising cast: political dissent and outrage. Word of cataclysmic state repression in China reached the United States in the late 1920s. American leftists were quick to listen. The curious name “Ding Ling” was on everyone’s lips.

The American Cultural Front represented a key, early site in the construction of a unified U.S.-China literary sphere in the first half of the century. By now, historical accounts of the Cultural Front are familiar: in the 1930s a diverse group of Americans—black and white, leftist and liberal, male and female—reacted to the social and economic crisis of the Great Depression by creating an integrated political movement that espoused civil liberties, social democratic politics, and cross-racial solidarity. Along the way, they transformed American modernism and mass culture. A critical aspect of this “front” was its international focus. Michael Denning has argued that the Cultural Front “transformed the ways people imagined the globe.” Solidarity with antifascist movements was not restricted to the nation; Cultural Front activists also conjured solidarity with populist struggles in Ethiopia and Spain. Denning reveals the U.S. Cultural Front as a complex “infrastructure” or “intricate network” that incorporated American social activism into broader global patterns of political dissent.1 At the same time, he distinguishes the Cultural Front from Soviet socialist internationalism. The two were in dialogue, but U.S. leftists did not take orders from Moscow. The American Cultural Front was its own thing, and its patterns of international affiliation were its own as well.

China is sometimes mentioned as one region of sympathy for the American Left. Cultural Front activists read about the Chinese Nationalist state’s violent repression of civil liberties and free speech. They felt inspired by Chinese left-wing political and cultural resistance and assimilated such efforts into their global leftist imagination. Americans offered moral support from a distance, but in most accounts that is where the story ends. The archive, however, tells a different story. American leftists were far more engaged with their Chinese counterparts than previously explored. The U.S. Cultural Front’s encounter with Chinese left-wing resistance exceeded mere sympathy or symbolic support. There existed rigorous and material forms of cross-cultural exchange and collaboration throughout the 1930s and early 1940s. American and Chinese writers actively communicated, worked together, and devised new forms of political and aesthetic expression. The Pacific was not an afterthought for the Cultural Front: it represented a robust opportunity to extend its core principles and ideas.

In developing a coherent U.S.-China leftist community, both American and Chinese intellectuals faced a significant challenge in making American political concepts commensurable in a Chinese cultural context, and vice versa. Specifically, the critical concept of “civil rights” or “civil liberties” stood as particularly vexing. In 1931 the arrest and incarceration of Ding Ling, an important Chinese author, and the national and international attention paid to her case emerged as an ideal test case for this question. The story of Ding Ling’s imprisonment and status as a cause célèbre for the Chinese leftist movement in Shanghai in the 1930s is well-known to China historians. Its international significance—both its appeal and its challenge to Western internationalists—has been less studied. American Cultural Front intellectuals and activists were especially drawn to this case and grew active in its unfolding. They found most compelling the question of whether the American concept of civil liberties, and more broadly liberal democracy, could be applied cogently and effectively in a place seemingly as alien and distant as Shanghai. How portable was the U.S. notion of civil rights? These questions set into motion a complex international campaign to liberate Ding Ling on the basis of a mutually imagined—for both Chinese and Americans—global civil liberties.

An obvious question is: why has a story of such significance not yet appeared in historical accounts of the U.S. Cultural Front? I argue that the international campaign to free Ding Ling required forms of writing and communication still unfamiliar to current interpretations of the American Left. Specifically, this campaign exploited new modes of technology, such as the telegraph, to build its case, and, most compellingly, it integrated the telegraph with more traditional forms of proletarian realism. The latter’s fusion with the telegraph allowed social realism to do things previously undreamt. It allowed it to move faster and more broadly, binding peoples and places seemingly infinitely distant both geographically and culturally to a shared domain of encounter. My argument is that the Ding Ling campaign demanded new forms of communication and expression to make possible the radical proposition of joining America and China to a common conception of “democracy,” and American and Chinese writers responded by creating a new mode of writing. The politics animated the aesthetics and vice versa. Studies of the U.S. Cultural Front have been slow to recognize communications technology as an important aspect of this movement. As a result, they’ve also been slow to discern the global versions of the Cultural Front that relied on such new technologies of communication.2

This chapter addresses two lacunae in U.S. Cultural Front scholarship: technology and China. It does so by focusing on the somewhat forgotten American left-wing novelist and journalist Agnes Smedley. Smedley makes possible this analysis: she served as a liaison between American and Chinese leftist intellectuals and played a key role in the Ding Ling international campaign. More conceptually, Smedley was at the forefront of articulating (on the ground, as it were) a vision of U.S.-China liberal democracy, and she created a distinct form of writing and communication to make this possible. I identify this literary practice as a “long-distance realism.” Despite her central place in the U.S. Cultural Front—her novel Daughter of Earth (1929) is considered one of the first examples of American proletarian fiction—Smedley has been largely excised from accounts of the American literary Left in the 1930s. It is precisely her commitment to causes and forms of expression that only in retrospect appear foreign to the American Cultural Front that has led to her scholarly exclusion. To return her to the center of this history is thus to enrich our conception of what the movement really was.

Limits of Radical Representation

American leftist and liberal interest in political dissent in Republican China dates back to the late 1920s. U.S. intellectuals affiliated with the American Civil Liberties Union, such as John Dewey, became increasingly aware of the Nationalist state’s suppression of free speech and persecution of labor leaders in Shanghai. Dewey had traveled to Beijing in 1919, where he lectured on the merits of democracy for fledging modern states such as Republican China.3 The early suppression of civil liberties under the Nationalist, or “KMT,” regime disturbed him, and he agreed to act as the chairman of a new ACLU national committee focused on providing legal defense for Chinese subjects targeted by the Nationalists.4 His efforts culminated in an ACLU pamphlet, “The Crisis in China,” which offered a careful analysis of the disturbing rise of Chinese totalitarianism in the mid-1920s.5 Nothing much seemed to come of this though: the ACLU archive grows quiet on China after the publication of this pamphlet.

American leftist interest in China resurfaced in the early 1930s. Again, the Nationalist state’s repression of labor activism and free speech commanded the bulk of the U.S. Left’s attention, but American intellectuals also started to focus on specific Chinese individuals. In the Labor Defender in late 1932, editors published a call to “demand freedom for Huang Ping,” a southern Chinese trade union leader who had been arrested by the Nationalists and faced execution.6 A string of similar articles appeared in the Labor Defender and other left-wing journals in the early 1930s.7 In each instance, American leftist writers such as Agnes Smedley extended sympathy to the growing Chinese leftist movement by humanizing its leaders and participants. By the late 1930s, reports about “the horrors of Shanghai” and names such as Huang Ping became a regular fixture in leading American left-wing and socialist periodicals.

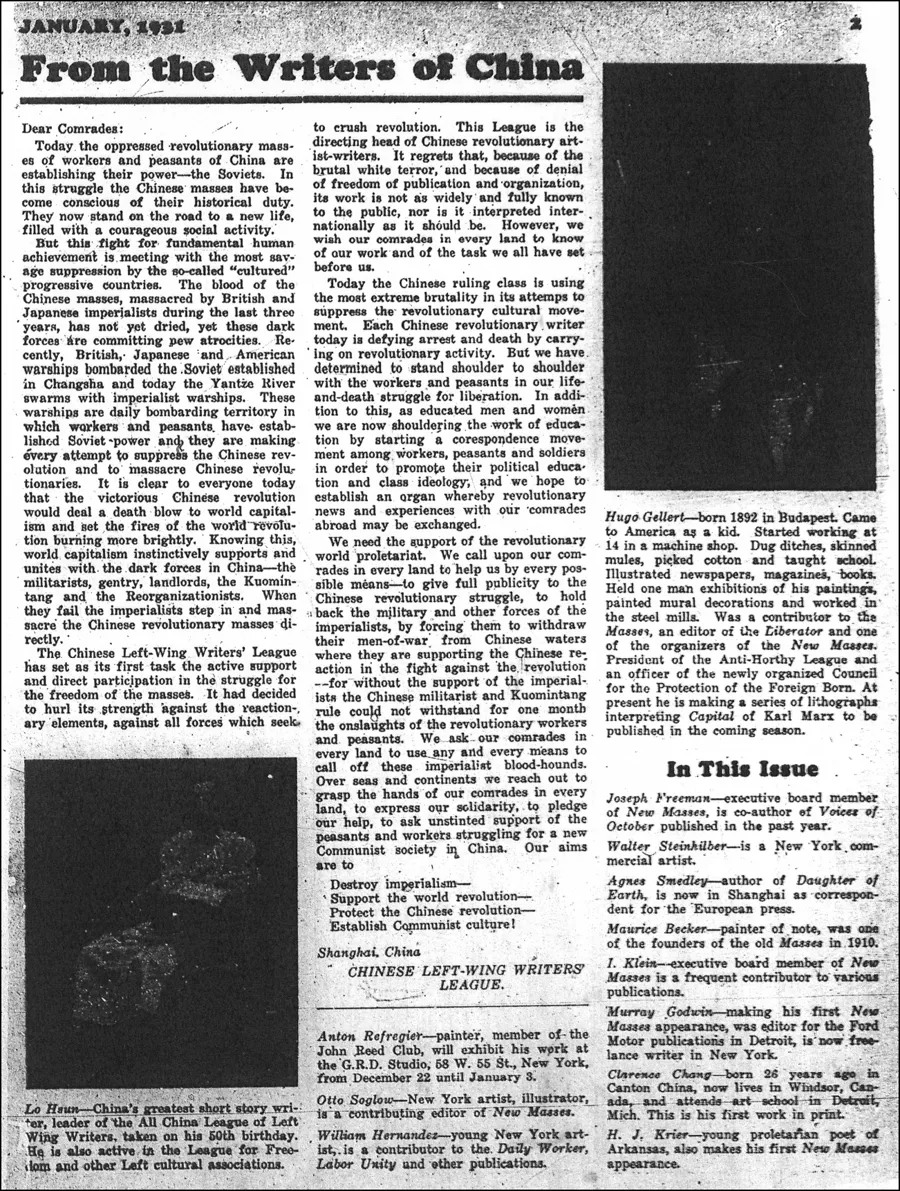

A high point of American leftist interest in China appeared in 1931 with the publication of a series of letters from the Chinese League of Leftist Writers. In the first letter, the league “call[s] upon our comrades in every land to help us by every possible means—to give full publicity to the Chinese revolutionary struggle” and concludes with a communist chant: “Destroy imperialism / Support the world revolution / Protect the Chinese revolution / Establish Communist culture!”8 In follow-up letters, the league strengthened its appeal by detailing the recent execution of five young communist writers (known as the “Five Martyrs”).9 The letters are themselves adorned with images of the five martyrs containing brief personal biographies. Finally, lending authority to this appeal is an image of the eminent Chinese author Lu Xun, who is described as “China’s greatest short story writer, leader of the All China League of Left Wing Writers.” The overall page layout is striking: the reader is assaulted by a litany of tragic political facts accompanied by a row of stark black and white photographs.

The American left-wing embrace of China in the 1930s is easy to contextualize within traditional narratives of the rise of the U.S. Left in this period. The Cultural Front arose as a response to the dual crisis of a post-1929 collapsing economy and rising fascism.10 The Great Depression exposed the inadequacy of conventional liberal notions of rational persuasion and the ideal of organic social community. Direct political action and social collectivism proved far more attractive to American intellectuals of the early 1930s. A more aggressive, muscular leftist politics, one committed to the “people” and economic redistribution, would serve to head off social chaos, as well as provide an alternative to totalitarianism.11 Chinese leftist intellectuals naturally faced a different challenge. The crisis was less economic and more political: unrelenting state repression consumed their attention and signaled the most obvious social threat. Regardless, U.S. leftists found it easy to find common rhetorical ground with their Chinese allies. Both, it seemed, were committed to a general ethos of “destroying imperialism” and “establishing communist culture,” and American intellectuals, such as Mike Gold (editor of the New Masses), seemed hardly bothered that those terms likely meant different things in different national contexts. The spirit of the U.S. Cultural Front was capacious enough to hear sameness in China. Journals such as the Labor Defender and the New Republic were eager to recognize the political crisis in China as symmetrical to the American Left’s own hard turn to socialism, and they assimilated it as such. Gold writes in an editorial in 1930: “Is there another John Reed in America? We would advise him to hasten to China, to be present at another ten days which will soon surely shake the world. Roar, China! Shake the pillars of this capitalist world. . . . Roar, China roar!”12

Figure 1.1 Article from the New Masses in 1931 reporting on the activities of the Chinese League of Leftist Writers.

Cultural Front interest in China neatly accords with another standard historical account of the American Left’s rise in the mid-1930s: internationalism. Visions of a “unity among all peoples of all nations” proved essential to U.S. leftists.13 A focus on the bonds that united different nationalities and races facilitated a more robust sense of “we, the people,” and effectively expanded the range of the Cultural Front movement. This “pan-ethnic appeal to a federation of nationalities both within the United States and around the globe,” Michael Denning reports, “was a powerful part of Popular Front culture.”14 In the American context, this disposition materialized as the melding of different races—black, Asian American, and Latino—into a single harmonious collective: Paul Robeson’s “Ballad for Americans” sung in different languages. In the international context, the Cultural Front undertook “solidarity campaigns” with emerging antifascist political campaigns in Spain and Ethiopia. A number of American leftists wrote about these movements in journals such as the New Masses. In each case, American intellectuals extend a profound sympathy to their overseas comrades. We can easily see Mike Gold’s support of Chinese political dissent in 1930 as merely an early, perhaps anticipatory, example of later left-wing solidarity campaigns.

Yet Chinese left-wing exchange with the American Cultural Front in the early 1930s aspired to do more than simply activate a “global imagination” for the U.S. Left. Its hoped for outcome extended beyond mere sympathy; both factions aimed to build a coherent U.S.-China left-wing literary public. Such a public would be reciprocal and broker the mutual exchange of ideas and materials. In this way, U.S. political radicals could do more than just observe the events in China from afar and assimilate its lessons as a part of its global political imagination. They could also directly test its core principles, such as “civil liberties,” in a foreign location, and perhaps vice versa. This desire is evident in a series of articles that Agnes Smedley wrote from Shanghai for the Nation, New Republic, and other periodicals. In “Shanghai Episode” (1934), she criticizes Westerners (Americans in particular) living in the International Settlement area in Shanghai for being complicit with the Nationalists’ suppression of free speech and civil rights. “The responsibility” for the deaths of countless Chinese left-wing writers, she claims, “must be placed at the doors of the British, American, and French governments whose agents rule Shanghai.”15 More broadly, she describes the happenings in Shanghai as a “whole tangled network” that necessarily implicates America and therefore requires U.S. political intervention.

Smedley brokered contact between American and Chinese left-wing writers throughout the 1930s and early 1940s. It was she who facilitated the publication of the Chinese League of Leftist Writers’ letters in the New Masses. While few Cultural Front figures in this period would argue that the United States and places like China or Ethiopia represented discrete, unrelated locations, Smedley more aggressively sought to unite America with the non-West through cultural exchange rather than mere sympathy or political analogy. America and China...