![]()

Channels of Communication in the Virtual Emirate

BEFORE THE ISLAMIC STATE publicized the immolation of its enemies on the Internet in 2015, and before Al Qaeda in Iraq disseminated videos of the decapitation of Americans online in 2004, the Taliban launched its website in 1998 (www.taliban.com). At that time, I was conducting research for an undergraduate thesis on militant movements in postcolonial South Asia. Aside from the Taliban, the only militant group to host a web-site was the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka. The Tigers used a basic point-and-click format, but the Taliban featured cutting-edge technologies; its home page opened with digitized American, Israeli, and Indian flags zooming into central view, exploding, then receding into the background to be overlaid by scrolling text in English and Urdu. Seventeen years later, the Tigers have been tamed by the Sri Lankan military, while the Taliban’s website for the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (www.shahamat.com) now includes text and multimedia sections of audio and video content in English, Arabic, Dari, Pashto, and Urdu. The multimedia sections indicate that the Taliban has been able to invest even more resources than before to host large files, indicating its ongoing popularity. Unlike other South Asian militants, the Taliban has expanded ambitiously to reach an audience in more languages than ever before. The name of the website is also illustrative: Arabist Hans Wehr defines the word emirate as “principality, emirate; authority, power” (1976, 27). The Taliban’s name for its website signals its ambitions for Afghanistan, envisioning a type of sovereignty based on an Islamic political system.

The Taliban clearly takes pride in its websites. In an interview posted on the Taliban’s official English website, Moulavi Mohammad Saleem—deputy head of the Cultural Commission for the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan—boasted that the Taliban’s multilingual websites are the most read in Afghanistan. Here, I reproduce the original quote, which contains grammatical errors:

If we take the internet department, the Islamic Emirate has a total of ten sites pulled together into one site. Pashto, Dari, Arabic, English, Urdu, Islam, video site, anthems, Al-Samood and Magazines site; all these sites are refreshed on the daily basis and fresh material is uploaded to them. Approximately more than 50 news items from all over Afghanistan is published in the sites of five languages i.e. Pashto, Dari, Arabic, Urdu and English. In addition, fresh incidents of the country and the world, interviews, reports, political and analytical articles, weekly analysis, messages and other material of literary touch is published. If we evaluate by the volume of the daily fresh news and moment to moment edit, we can say with full satisfaction that Alemarah [“the Emirate” in Arabic] site is the richest and widest read site on the level of Afghanistan. (Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan 2013a)

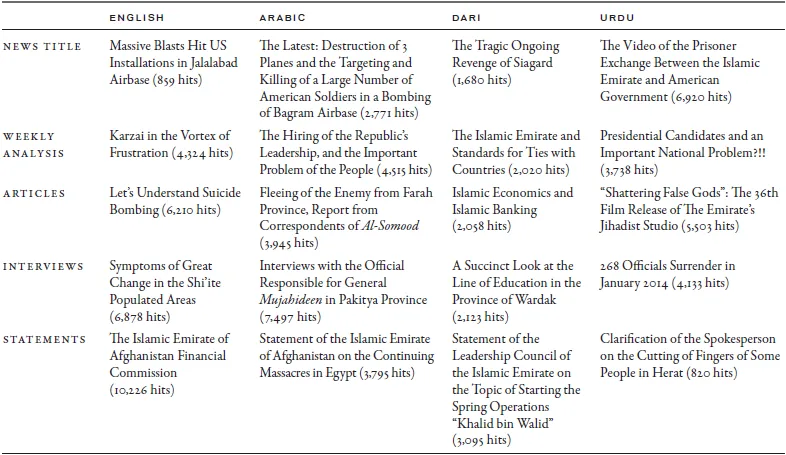

Table 1.1 lists the total number of hits for the most accessed web content by language since publication on the Taliban’s websites. The Urdu news section article boasts close to seven thousand hits, compared to nearly nine hundred for the English news section article. The most-accessed statement in English exceeds ten thousand hits, more than that for the Arabic, Dari, and Urdu statements combined. These variations suggest that there are differences in how people access this content, with Urdu speakers possibly relying on the Taliban’s websites for primary reporting compared to speakers of other languages. The high number of hits for the English statement may be due to the number of readers abroad, such as supporters, journalists, scholars, and people who are curious about the Taliban’s Internet presence. Reports of military triumphs in Afghanistan coexist with statements on international affairs (i.e., Egypt), suicide bombing, and Islamic finance. This diverse range of topics points to the role of the Taliban’s websites in promoting a distinctive worldview beyond the war in Afghanistan.

Furthermore, if we take the Taliban at its word, its websites front an enormous enterprise. This interview fragment implies an expensive and expansive undertaking. This quote is longer than others in the book, but I have found no other text that better encapsulates the range of activities or resources of the Taliban and gives us a sense of its day-to-day activities. Even if this text is pure propaganda, it imparts an understanding of the types of values that the Taliban prioritizes for its audiences:

TABLE 1.1 Content with Most Accessed Hits by Language on the Taliban’s Websites*

* Statistics were tallied on June 27, 2014. The Taliban has not listed statistics for Pashto websites.

At present, the high commissions of the Islamic Emirate are as following though all of them have vast set-up[s] within themselves: Courts, Military Commission, Commission of Cultural Affairs, Education Commission, Invitation and Guidance Commission, Health Commission, Organ for the Prevention of Civilian Casualties, Commission for Prisoners’ Affairs, Organ for Martyrs, Orphans and Disabled persons, Commission for Political Affairs and Commission for NGO’s Affairs.

As far as the responsibilities are activities of these commissions are concerned, I would like to give you the example of [the] “Health Commission.” This commission is responsible for [the] wounded, paralyzed, [and] disabled as well as the treatment of those Mujahidin who are released from jails. You can imagine that the number of wounded and disabled people in the prolonged battle of Afghanistan is quite large[,] and every year it is increased by thousands. According to the estimations of the “Health Commission,” the average expenditure of every wounded, disabled or paralyzed one reaches to 200,000 Afghanis which is equal to more than 4000 dollars. The expenses of some seriously wounded persons soar several times higher than this.

The “Commission for Prisoners’ Affairs” provides cash money to the incarcerated people in all jails of Afghanistan. You might be aware that tens of thousands of innocent Muslims are lying in various jails of Afghanistan without any charges. Being a responsible and committed Islamic movement, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan reckons it one of its foremost responsibilities to assist all the incarcerated people within the range of its possibilities. Therefore, it has established a separate organ for this purpose to support the oppressed detainees financially for getting treatment and meeting daily expenses.

The “Commission for Martyrs, Orphans and Crippled Affairs” is responsible for collecting the lists of all those children who are orphaned after the American invasion in all the 34 provinces of Afghanistan. Their detailed bio-data is assembled; then, they are supported. Similarly those people, who are paralyzed or disabled undyingly, are also supported financially on the permanent basis. There is [a] large number of people in our society who lost both of their legs, hands or both eyes. They do not have any source of income apart from the Islamic Emirate to support their families and offspring.

Besides supporting them financially, the “Educational Commission” of the Islamic Emirate has also set up orphanage centers for them so that these helpless children should not remain uneducated. Similarly, the “Invitation and Guidance” or “Attraction and Absorption Commission” is responsible for guiding those people who are working side by side with the American infidels. This commission tries to separate these people from the enemy. The “Commission for the [P]revention of [C]ivilian [C]asualties” tries its best to save civilian and defenseless Afghans from war miseries. In case the civilian losses occur, this commission is responsible to financially assist the suffering families. Likewise, all the above[-]mentioned commissions perform their assigned duties and have heavy expenditure. (Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan 2014c)

In order to compete with the Afghan government and be seen as a viable political alternative, the Taliban proudly advertises its expansive administration, flush resources, and vast network. This undertaking finds a historical precedent in the mujahideen resistance movements of the 1980s, which created alternative systems of government to the Soviet Union–backed Kabul regime in approximately 80 percent of the country (Amin 1984). This quote also illustrates the Taliban’s ideological mission to rule over Afghanistan once again, as it did from 1996 to 2001. These types of texts from Taliban authors can teach us about their military strategy, sociopolitical perspectives, and campaigns for recruitment. Currently, we have little academic research on Taliban texts, besides cursory overviews of Taliban periodicals in different languages (Chroust 2000; Nathan 2009). This trend reflects the general state of scholarship on the Taliban, with most studies relying on American military and civilian sources (Farrell and Giustozzi 2013). Instead, studies exploring the Taliban’s internal perspectives have typically involved interviews with Taliban leaders to explain the group’s post-2001 resurgence (Giustozzi 2009, 2012; Malkasian 2013; Strick van Linschoten and Kuehn 2012a; Bergen and Tiedemann 2013). The few textual studies include translations and analyses of a former minister’s autobiography (Zaeef 2010), original poetry from rank-and-file members (Strick van Linschoten and Kuehn 2012b), and the Layeha, a military code of conduct for militants (Shah 2012; Johnson and DuPee 2012). We know little about the Taliban worldview, even though the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have surpassed $1.6 trillion and 145,000 deaths (Watson Institute 2013), and American military involvement in Afghanistan has exceeded all other wars. For example, while we know that the Taliban has fought American-led coalition troops as enemies, we do not know how they have managed to stage a successful resistance over the years. Analyzing Taliban texts allows us to observe cultural and psychological trends of the organization as they relate to a wide range of issues.

Surprisingly, the Taliban’s multilingual publications demonstrate a trend of ideological flexibility that sharply deviates from its history of cultural, social, and political rigidity. In the next section, I synthesize Taliban primary sources and key works of secondary scholarship to chart the Taliban’s trajectory from the 1990s to contemporary times. This information provides a context in which to consider why a militant organization pledging to replicate the conditions of seventh-century Arabia in Afghanistan has sought to exploit twenty-first-century multimedia technologies so effectively.

THE GROWTH AND EVOLUTION OF THE TALIBAN

After the 1989 retreat of the Soviet Union from Afghanistan and the 1992 fall of the Soviet-backed Mohammed Najibullah government, Islamist resistance groups—known as the mujahideen (“warriors” in Arabic) and previously funded by the United States, Pakistan, Iran, and Saudi Arabia—turned against one another to carve the country into exclusive spheres of influence (Nojumi 2008). The Taliban formed in 1994 to oppose these groups, which had taken to plundering populations and raping minors, vowing to disarm rival commanders, establish peace, and purify society by implementing Islamic Shari’a law throughout Afghanistan (Marsden 1998; Goodson 2012). Taliban radio broadcasts reiterate the centrality of jihad to justify violence, whether against atheist Soviet Communists or enemy warlords accused of conspiring with foreign governments (Kleiner 2000). The Taliban’s website in 1998 portrayed a scenario perceived as wanton depravity:

Conditions deteriorated to such an extent that the people cried out in anguish. They were now [ready] even for Russia or a power even much worse to take command of their country. They only asked to be delivered from their sufferings. Their misery know [sic] [no] bounds. No one’s wealth, life or honour was safe anymore.

Cities became deserted after Asr prayers, before the sun had even set. People did not dare to venture outside their homes. Tired after the day’s work, they had yet to keep awake to guard their homes. Even then they were not safe. During the daytime too no one dared to venture out with their wives, daughters or sisters, out of fear for their honour and safety.

People had sent their handsome, teenage sons to Pakistan as it had become extremely dangerous for them to venture out in the streets. Homosexuality, adultery had become so common that it is said a boy married another boy in Kandahar. Many people joyously celebrated the wedding, ringing the death-knell of all decency, all that is good and honourable. (Taliban 1998)

The Taliban represents the time before its rule as a dark period of desperation, deserted cities, dishonor, and decadence, with constant insecurity. Immorality is described as sexual relationships outside of any heterosexual marriage, whether in the form of adultery or homosexuality. No division exists between public and private lives in this commentary: all forms of personal behavior that are deemed immoral are also connected to crimes committed in public.

The Taliban soon attracted international attention. American officials believe that the Taliban’s initial funding came from Afghan traders who wanted to smuggle goods from Central Asia to South Asia through Afghanistan. The civilian Pakistani government of Benazir Bhutto later provided jets, diesel fuel, ammunition, and artillery and weapons training (Holzman 1995). Other Pakistani military officials increased their support throughout 1994 by using private transportation companies to supply “munitions, petroleum, oil, lubricant, and food” (U.S. Intelligence Information Report 1996). Many Pakistani civilian and military elites commonly viewed the Taliban as a force to purify Islam of heretical groups through jihad (Cohen 2004). The Taliban recruited hundreds of Pashtun students from madrasas (Islamic schools) in Pakistani refugee camps. By 1998, these students had imposed Shari’a law, modeled on the Prophet Muhammad’s society of seventh-century Arabia, on 90 percent of Afghanistan (Rashid 2002). Pakistan’s Grand Mufti Rasheed Ahmad Ludhyanvi praised the Taliban’s attempt to implement Shari’a law: “In the areas under the Taliban Government every kind of wickedness and immorality, cruelty, murder, robbery, songs & music, TV, VCR, satellite dish, immodesty (be-purdagi) [literally ‘being unveiled’], travelling without a mehrum [a male companion for women], shaving-off or trimming the beard, pictures & photographs, interest, have all been totally banned” (Moosa 1998). Most of the Taliban’s leadership passed through two Pakistani madrasas, the Darul Uloom Haqqani at Akora Khattak and the Jamiatul Uloomil Islamiyyah in Karachi (Matinuddin 1999).1 Taliban writers have proudly proclaimed these affiliations:

The Taliban leadership, Al hamdu-lilLah [Praise God] comprises of Saheeh-ul-Aqeedah [True of Faith] Deobandi Muslims. They proclaim themselves that they belong to the Maslak-e-Deoband [Path of Deoband] which admits to no excesses but is firmly based upon moderation. We ourselves are a witness to the fact that the common Taliban leaders are former students of famous Deobandi Madaris [schools] of Pakistan. Jami’a Haqqaniyyah, Akhora Khattak, Peshawar; Jami’at ‘Uloom-ul-Islamiyyah, Binnori Town; Dar-ul-Uloom Karachi; Jamia Farooqiyyah; Jamia Hammadiyyah; Dar-ul-Ifta-e-Wal Irshad, Nazimabad and other Madaris of Pakistan and Afghanistan have been their seats of learning. (Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan 1998a)

The references to “Deoband” and “Deobandi” refer to the educational orientation of the madrasa network attended by the Taliban. Begun in 1867 in Deoband, India, the Dār ul-’Ulūm seminary adopted a standard syllabus of Quran and Hadith study, central exams, and professional staff in all branches, promulgating a common theology throughout Muslim South Asia that contrasted with an older model of oral learning between teachers and students (Metcalf 1978). Since 1914, Deobandi scholars have triggered political mobilization in Pakistan’s Pashtun territories by controlling mosques and madrasas. Abdul Haq, founder of the aforementioned mosque at Akora Khattak, oversaw the graduation of 370 Afghan students between 1947 and 1978 and converted his mosque into a center of jihad after the Soviet invasion (Haroon 2008). Despite the Taliban’s claims of adhering strictly to Deobandi principles, leading Deobandi scholars in Pakistan have openly disagreed with the Taliban, encouraging it to educate girls and to resolve the crisis with the United States over Osama bin Laden after 9/11 in the best interests of Pakistan and Afghanistan (Zaman 2002).

The mention of Pakistan in the Taliban’s quote also reflects disruptions in traditional Afghan society. Power dynamics have traditionally divided urban political elites who represent the state and rural tribal chiefs and spiritual leaders (Ghani 1978; Roy 1990). Religious scholars worked as state employees without an independent followership until the 1960s, when they demanded political participation—inspired by Islamist movements in Egypt, Pakistan, and Iran—and conducted political activities underground in the 1970s due to opposition from the Soviet-backed Kabul regime (Naby 1988). The erosion of social institutions during the 1980s war—such as the landlord-dominated rural economy and the state madrasa network—decentralized education to local mosques, whose leaders looked to religious scholars now housed in Pakistan (B. Rubin 2002). Many madrasa students in Pakistan were Afghan children who lost parents during the war; thus, the Taliban can be seen as an orphan youth movement transcending ties of tribe and kinship to form a group identity based on religion (Fergusson 2010).

In addition to seeking official government support, the Taliban has appealed to Pakistani civilians. The following 1998 appeal from the Al-Rasheed Trust calls for donations of animals for helping hungry and destitute Afghans.2 The trust’s branches in major Pakistani cities attests to the Taliban’s national nexus:

Al-Rasheed Trust requests all Muslims in general, supporters of the Taliban and readers of Dha’rb-i-M’umin [a periodical] in particular, to offer their “Wajib” [obligation] and “Nafl” Qurbani [sacrifice], in Kabul, Herat, Badghis and Kandhar [sic], on the occasion of ‘Eid-ul-Adhha. Besides the “Wajib” of Qurbani, they would thus be discharging their “Fardh” [duty] of helping the poor and needy, the Taliban Mujahideen, families of the Shuhada [martyrs], thousands of destitute widows and orphans too. According to Mulla ‘Abdul Jaleel Sahib, the cost of a medium sheep is Pak. Rs. 3,000/ or U.K. Pounds 40/ or U.S. Dollars 65/, only. The cost of the Qurbani can be deposited in the Trust’s branches i...