![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A Thousand Modes of Venery

Coital Positions as Actions and Communications

A GLANCE AT THE ANIMAL KINGDOM presents us with an astounding variety of sexual relations, yet such heterogeneity tends not to apply within individual species. Humans, on the other hand, while we share sexual flexibility with certain relatives among the higher primates, have developed it in theory—if not always in practice—to a significantly greater degree. We have created esoteric traditions in which certain positions might only be attained with the aid of complex instructions, diagrams, and physical training; we have also produced rather pedestrian handbooks of the more easily executed positions for everyman and everywoman. There is a fair amount of reflection from antiquity to the present on what to make of the fact that we need not engage in intercourse in the naturally prescribed manner, if such a manner can be said to exist at all. Consider pioneering sexologist Iwan Bloch’s description of proper congress in his The Sexual Life of Our Time in Its Relation to Modern Civilization (1908): “Passing to the consideration of the posture adopted during intercourse, we find in civilized man, who in this respect is far removed from animals, the normal position during coitus is front to front, the woman lying on her back with her lower extremities widely separated, and the knee and hip joints semiflexed; the man lies on her, with his thighs between hers, supporting himself on hands or elbows—or often the two unite their lips in a kiss.”1 With the expression “lower extremities” substituted for the ordinary “legs,” Bloch clearly intends that we take his description as clinical and as if microscopic. But the rhetoric of empiricism notwithstanding, Bloch’s evidence appears anecdotal. When he does provide sources, these are usually references to the work of other sexologists. He also turns for support to what we now class as literature. Bloch oversaw the first publication of Sade’s manuscript of Les 120 journées de Sodome, a work that he considered a compendium of pathological practices that, for lack of a disciplinary framework, was forced to appear in fictional form. It was Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis (1886) in gothic dress.

Although Bloch speaks confidently of “the posture,” his qualification that this refers us only to “civilized man” confirms that the facts of life have a social and historical dimension. Attempts at description, moreover, shade off into prescription. Bloch does note that there are other positions possible, but the only ones that “demand consideration on hygienic grounds” are “lateral decubitus of the woman, dorsal decubitus of the man, and coitus a posteriori (for example, when the man and woman are extremely obese).”2 He puts these positions quickly aside and, citing anthropological authority regarding its universality and naturalness, returns posthaste to the preferred mode: “Ploss-Bartels has proved that the position described above as normal was usual already in ancient times and amongst the most diverse peoples. The adoption of this position in coitus undoubtedly ensued in the human race upon the evolution of the upright posture. It is the natural, instinctive position of civilized man, who in this respect also manifests an advance on the lower animals.”3 In Bloch, instinct and civilization are peculiarly conflated. In the front-to-front position, the meeting of the genitals below in copulation is counter-balanced with the meeting of heads above in osculation. Intimacy, spirituality, and rationality are hereby injected into an act otherwise shared with animal-kind; it is elevated, civilized, and humanized. Man on top, of course, in keeping with the natural order of patriarchy.

In spite of moral laxity and sex education, we might wonder how far we have come from the days when sexology was not ashamed to advertise its normalizing impulse. Although here it is my evidence that is anecdotal, I would wager that if an educated North American—or an uneducated one for that matter—were asked to name positions for coitus, he or she would likely only be able to come up with two or three designations. One of these would be missionary. The word might be delivered with a sniff of disdain and, for those disposed to irony, accompanied by a wink to suggest that below the surface of Christian zealotry and justifications for imperialism lie hidden libidinal springs. But, while it is somewhat surprising that a term so pungent with white man’s burden should have survived into postcolonial times, is there a common alternative besides normal or usual? Another position would be the colloquial doggy style. The canine reference has long been common in English. In The School of Venus (1680), a free translation of the École des filles, we find a woman explaining that her paramour took her “Dog fashion, backwards.”4 Out of modesty, pedantry, or perhaps simple love of learned archaism, one might with Freud intone a tergo, more ferarum (from behind, in the manner of beasts).5 In either the classical or vernacular tongue, the supposed animality of the position would be emphasized. This is something more pronounced in the Latin, where ferae are specifically wild as opposed to domesticated animals. Here we are reminded of what Freud wrote concerning the upright carriage of homo sapiens, civilization, and the disparagement of olfaction: “It would be incomprehensible…that man should use the name of his most faithful friend in the animal world—the dog—as a term of abuse if that creature had not incurred his contempt through two characteristics: that it is an animal whose dominant sense is that of smell and one which has no horror of excrement, and that it is not ashamed of its sexual functions.”6 Our modern addition of a diminutive suffix to dog suggests further repudiation and embarrassment.

Many of the concerns that both Bloch and Freud express are those of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The implied notion that civilizations are at different evolutionary stages is redolent of Herbert Spencer, whose enormous influence was on the wane but whose theories were still part of the zeitgeist. Yet the guiding binary of human-versus-animal with respect to sexual positions is so prevalent across time and space that we might rightly wonder if it should be treated as a universal. Could it be that, along with the incest taboo, the two most frequently mentioned manners of coitus provide a foundational opposition for culture tout court? Although the topic of sexual positions has not, that I know of, ever been taken up by structural anthropologists, it would be worthy of such an analysis. The opposition of the two main manners of intercourse is analogous, for example, to a guiding binary that Lévi-Strauss saw as a cultural universal: the raw and the cooked.7 Moreover, it links up nicely with another fundamental opposition: the dirty and the clean, often tied to matters of civilization and imperialist ideology.8 While there may well be something to this universalization of the distinction between human and animal with regard to sexual positions, we must nonetheless pay careful attention to historical particularities, linguistic subtleties, and local—including libertine—differences on this score. Furthermore, the binary simply does not take into account the myriad other ways that humans can engage in coitus or have imagined doing so.

Bloch himself should have been fully aware that the actual multiplicity of positions threatened to undermine the function of positing the “normal manner,” which was to suggest that there is an instinctual trend to civilization. I point this out not because I want to indulge in attenuated deconstruction. It would be easy enough to show that sexology from this period tends to work with binaries that quickly crumble on closer inspection. These are not deeply philosophical texts. More interesting is that the instability of the structure of these texts is directly related to sexology as process: such binaries must be produced, reaffirmed, and then systematically destabilized in order to generate meaningful data. For example, Bloch must constantly open up and close down the paradox that the abnormal is normal.9 Thus, on the one hand, he notes that because “sexual anomalies constitute a phenomenon generally characteristic of the human race, race and nationality, as such, have less to do with the matter than is commonly imagined.”10 The abnormal is normal—or at least is evenly distributed throughout human populations. On the other hand, after denying a couple of stereotypes, he goes on to note that among so-called Semitic peoples, “the Arabs and the Turks” stand out as “sexually perverse nations.”11 Here the normal is abnormal. The question of positions comes up explicitly in this regard: “Among the Aryan races the Aryans of India must be considered pre-eminent as refined practitioners of psychopathia sexualis, which they have reduced to a system. In addition to recognizing forty-eight figurae Veneris (different postures in sexual intercourse), they practise every possible variety of sexual perversion; and they have in various textbooks a systematic introduction to sexual immorality.”12 Alongside hygiene and Spencerian social evolutionism, we recognize in Bloch’s description the biologization of race and the concomitant concern about degeneration. There is also a healthy strain of Orientalism in a sense close to that made current by Edward Said, for whom the “Orient” was constructed by nineteenth-century scholars as a static, ahistorical contrast to a progressing West.13 For Bloch, certain “others” are, in a way, hypercivilized to the point where complexity leads to degeneration (Turk, Arab, and Indian, to name the most important cases). What interests me here primarily, however, is that Bloch attributes to such degenerate nations exactly the same knowledge that forms the basis of his own discipline: a psychopathia sexualis. And while to practice this is apparently immorality, there is no small irony in the fact that without such perversion and variety the scientist would have very little to do. The price of universal normalcy would be the end of sexology.

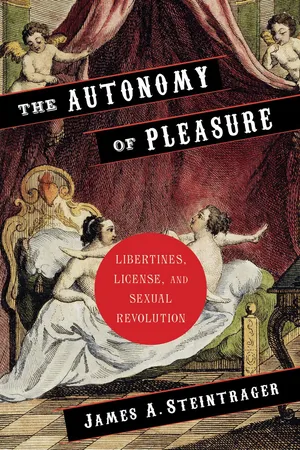

Alongside the multiplicity among “other” nations, another problem with Bloch’s depiction is that some of the terms of his Orientalist discourse could just as easily apply to certain epochs of Western history, and not particularly distant ones at that. Given the knowledge he had of Sade and other libertine writers, Bloch must have been adept at compartmentalizing his data. An example from revolutionary France entitled Les Quarante manières de foutre (1790) makes the conundrum clear.14 The little pamphlet describes how to get into various sexual positions and includes accompanying illustrations. Our paucity of terms does not afflict this work: we find alongside la bonne mode, or “proper manner,” and en levrier, or “greyhound style,” a variety of other postures. These include “the cavalcade,” “the windmill,” “the world upside-down,” “the mare of Father Pierre,” “the extremity,” “the swimming frog,” “the pouter,” “the reconciliation,” “the bawdy clyster,” “the nursemaid,” and many more (figures 1.1 and 1.2). There is already a bit of Orientalism here too, although perhaps exoticism is the more appropriate term. For example, one position is named la sultane and another la chinoise. But these are folded into the enumeration of the many others. The Quarante manières de foutre is a rather late entry in the Western tradition of the “postures”: descriptive catalogues, often inserted into fictional narratives, of the variety of ways in which human male and female may join in coition. The very existence of this tradition shows the precariousness of Bloch’s ideological position. It also undoes the assumptions of more recent—and more readily praised—work on the history of sexuality, notably complicating Foucault’s assertion that the modern West alone has broken with the tradition of the ars erotica and produced in its stead a scientia sexualis. Although he traced its roots to ancient Roman attitudes and Christian pastoral care (especially the development of the sacrament of confession), Foucault located the emergence of the “discourse of sexuality” largely in the eighteenth century. He specifically mentions Diderot’s Bijoux indiscrets as an almost literal allegory of this emergence: the date when sexuality became a secret that would henceforth endlessly be incited to speak its truth.15 But it seems that at the very moment Foucault chose to locate the emergence of the discourse of sexuality as such, libertine writers were busy not only extending the Western erotic tradition but also inserting it into and thereby constituting a specifically libertine scientia.16

In the following pages I will examine the tradition of the “postures” as it appears in licentious literature from ancient Rome to the Renaissance and through the eighteenth century, considering how an already complicated erotics—complicated because thoroughly enmeshed with satire and rhetoric—became increasingly systematized. The “postures,” moreover, help me open a question that is crucial to my overarching project: Does it make sense to speak of pleasure as a social system? In Leviathan Hobbes provides a complex model of the human psyche and catalogs a variety of passions and subpassions: “griefe,” “hope,” “despaire,” “courage,” anger,” “confidence,” “ambition,” “pusillanimity,” “magnanimity,” “valor,” “liberality,” “miserableness,” and “kindeness,” to name only a few.17 When it comes to constructing his social system, however, it is the three causes of “quarrel” embedded in human nature that determine the need for and nature of the compact with a sovereign: “competition,” “diffidence,” and “glory” all lead to the war of every man against the other unless there is a “common power to keep them in awe.”18 This simplification has enormous explanatory power: it helps us grasp the origins and nature of society as well as suggesting how a community might best be ordered. In the eighteenth century, libertinage made use of a similar simplification to construct a sort of idealized hypothetical model of society, but it took what was often specified as physical—as opposed to moral—love and what Hobbes himself calls “Natural Lust” or “Love of Persons for Pleasing the sense only” as the driving force of social relations rather than fear and copulation rather than contract as its elemental bond.19 To take up the terms of the Histoire de Dom Bougre (1741): “pleasure is the primum mobile of every human action” (“le plaisir est le premier mobile des toutes les actions des hommes”).20 One advantage this decision concerning the ultimate source of our actions had over Hobbes’s conception was that it dispensed with the need for a political sovereign to overawe by force and fear. Reduced to coitus, the sexual compact could be conceived as conspicuously natural—a conjunction of bodies that b...