![]()

1

“Like the snow on the Alps”

After Nature

CROSSING BORDERS

Whoever opens After Nature (Nach der Natur) might well be lost. The epigraph to the first of its three poems invokes a guide, but what reader would thereby be given hope?

“Now go, for a single will is in us both:

Thou guide, thou lord, thou master,”

So I said to him; and when he had set forth

I entered on the steep wild-wooded way.1

Dante, led into the Inferno by Virgil, is taken on a wooded way (which will eventually find echoes in Sebald’s poem) and follows his guide with blind abandon. That we are on the way to hell in Sebald’s first major literary publication, in the first of the three poems that comprise that work, is not immediately evident. But we might be struck from the outset by its title, which cites, not the opening phrase of the poem, the customary gesture for titling a text, but, rather, its closing words: “like the snow on the Alps” (After Nature, 37E, 33G).2 The poem, devoted to the sixteenth-century painter Matthaeus Grünewald, thus anticipates its own end, makes it foregone. With the phrase “like the snow on the Alps” it might also seem to celebrate nature, or at the very least its own capacity to paint therefrom (Nach der Natur). We will see.

Like its title, the beginning of the poem asks us to think the relation of opening and closure. It is a question of how we have access to a work of art, what kind of art that is, and how it relates to those outside it.3

Whoever closes the wings

of the altar in the Lindenhardt

parish church and locks up

the carved figures in their casing

on the left hand panel

will be met by St. George.4

(After Nature 5E)5

To be met by the work of Matthaeus Grünewald, perhaps that of Sebald as well, one must perform a certain task. We must close the door on, withdraw from sight, certain kinds of figures. Carved and three-dimensional, to them belongs a casing or housing that guarantees fixed place. We must lock these away, with their attempts at rounded replication, and give ourselves over, rather, to what comes to meet us. We are called to an encounter—if not yet to account.

Foremost at the picture’s edge he stands

above the world by a hand’s breadth

and is about to step over the frame’s

threshold. Georgius Miles. . . .

(After Nature 5E)6

Floating just slightly above the earth, nothing fixes St. George in place—much less grounds or closes him in. Poised on the border of image and world, he is about to cross the threshold between painting and beholder. This permeability of the work of art, this crossing of borders—an interchangeability of spaces, of figures, of times—will have a crucial role to play across the parts of After Nature as well as in each of the four works to follow, in The Rings of Saturn, Vertigo, The Emigrants, and Austerlitz.

On the facing panel, another wanderer: the older man, St. Dionysius, is Matthaeus Grünewald’s chosen protector:

at the centre of

the Lindenhardt altar’s right wing,

that troubled gaze upon the youth

on the other side, of the older man

whom, years ago now, on a grey

January morning I myself once

encountered in the railway station

in Bamberg. It is St. Dionysius,

his cut-off head under one arm.

(After Nature 6–7E)7

If St. George is poised to enter our space, Dionysius had already done so—jumped the frame and made it to the other side. Doubly. First with his eyes, directed toward the youth on the facing panel—but, also, crossing out of the painted surface, out of the sixteenth to the twentieth century—to the Bamberg train station where the narrator had seen him years before.8

St. George is about to step over the threshold to us, leaving his dragon yet to be slain. St. Dionysius has already, without our knowing, entered our world. “In the midst of life [Dionysius] carries his death with him” (After Nature 7E, 8G) in the form of his own severed head. Perhaps it is this one face too many (the dead one with the closed eyes) of the saint that allows him to wander out of the work of art and into the everyday life of the author. Closed eyes, a death of sorts, may be the ticket to Sebald’s many railway stations.

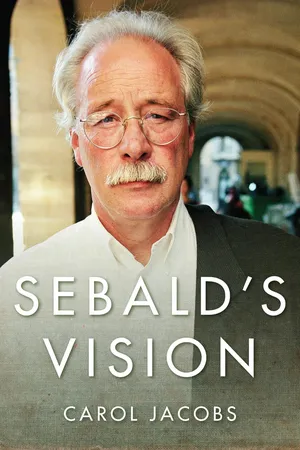

Saints George and Dionysius may wander among us. Access to Grünewald is another matter. “The face of the unknown / Grünewald emerges again and again in his work” (After Nature 5E, 7G) in St. George to begin with, as well as in the work of Holbein and others. In a barely disguised instance of resemblance, how can one fail to recognize also Sebald’s eyes, sliding sideways in so many photos as though burdened with grief and loneliness?

Always the same

gentleness, the same burden of grief,

the same irregularity of the eyes, veiled

and sliding sideways down into loneliness.

. . .

These were strangely disguised

instances of resemblance, wrote Fraenger

whose books were burned by the fascists.

Indeed it seemed as though in such works of art

men had revered each other like brothers, and

often made monuments in each other’s

image where their paths had crossed.

(After Nature 6)9

The staged coincidences, connections, similarities, the rupture from the image world to its apparent other, the temporal volt over a threshold of centuries that seems to divide the past from the present and death from life,10 the haunting by a Holocaust never quite absent: throughout the works of Sebald, these are defining gestures—also the irregularity of eyes that cannot be ruled.

DEPICTIONS

If his face is to be found in various forms, depicted by various hands, still: “Little is known of the life of / Matthaeus Grünewald of Aschaffenburg” (After Nature 9E, 10G). If not the life, then might we know the works? They come to us at first indirectly, if at all (in section II of the poem) by way of “The first account of the painter / in Joachim von Sandrart’s German Academy / of the year 1675” (After Nature 9E, 10G). There we read of one work, lost since the nineteenth century, and of another, looted and lost in a shipwreck, and of other paintings that Sandrart also never got to see. Nevertheless, we are asked to trust the report of Sandrart, since an image of him in the Würzburger Museum shows him at eighty-two “wide awake and with eyes uncommonly clear” (After Nature 9E, 10G). The clarity of the critic’s eyes alongside the irregularity of the painter’s: what are we to make of this?

Might we speak of the clarity of the critic’s eye in the narrative of After Nature? There are many verbal depictions of Grünewald’s images, pages on pages of them: the Lindenhardt Altar with its St. George and St. Dionysius, the fourteen auxiliary saints, Cyriax and Diocletian’s epileptic daughter, the self-portrait in the Erlangen library, the trans-figuration of Christ on Mount Tabor, the blind, murdered hermit on the Mainz cathedral altar panels, the self-portrait of Nithart in the Chicago Art Institute, the Sebastian panel, the Isenheim altar, the Basel Crucifixion of 1505, the temptation of St. Anthony in all its excruciating detail, all these are laid out before the mind’s eye. Take the following passage, a scene from the temptation of St. Anthony, but, surely, also, the fulfilled premonition of hell announced in the epigraph.

Low down in the bottom-left corner

cowers the body, covered with

syphilitic chancres, of an inmate

of the Isenheim hospital. Above it

rises a two-headed and many-

armed androgynous creature

about to finish off the saint

with a brandished jaw-bone.

On the right, a stilt-legged ...