![]()

· 1 ·

BLACK BOXES AND OPEN-AIR STAGES

FILM STUDIO TECHNOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL FROM THE LABORATORY TO THE ROOFTOP

It obeys no architectural rules, it embraces no conventional materials and follows no accepted scheme of color. Its shape, if anything so eccentric can be entitled to that appellation, is an irregular oblong. . . . Its color is a grim and forbidding black, enlivened by the dull lustre of myriads of metallic points . . . the uncanny effect is not lessened, when, at an imperceptible signal, the great building swings slowly around upon a graphited centre, presenting any given angle to the rays of the sun and rendering the apparatus independent of diurnal variations.

—W. K. L. Dickson and Antonia Dickson (1895)1

IN LATE 1892 at Thomas Edison’s laboratory in West Orange, New Jersey, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson designed an architectural space like few seen before. Soon dubbed the Black Maria—a colloquialism for police paddy wagons—the building was variously described by contemporary observers as a coffin, cavern, or outright conundrum. Today it is better known as the world’s first film studio. Dickson developed the studio concurrently with two of Edison’s better-known moving-image machines, the Kinetograph and Kinetoscope, and the studio was integral to Dickson’s work on these devices. Each operated on the same principles: the juxtaposition of light and dark, the interplay of movement and stasis, and the technological reproduction of nature. Much like the camera and projector, studios like the Black Maria allowed Dickson, Edison, and the inventors, artists, and image-makers who followed to create new forms of visual representation and to contribute to the emergence of new conceptions and experiences of modern technological space.

The Black Maria remains an often-celebrated icon of early film history and a companion “first” to Edison’s moving-image apparatuses. Unlike those devices, however, historians and theorists have paid insufficient attention to its formal genealogy and, as a result, its importance for theorizing film space.2 Indeed, observers dating to Dickson himself have too quickly accepted the idea that the studio was simply a singular, idiosyncratic form, and that “modern” studios soon made its “primitive” design little more than a souvenir of film history. Such characterizations deny the complexity of the structure’s form and function, its historical roots, and the spatial predecessors that contributed to Dickson’s design. These spaces—which included the Edison laboratory, Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey’s respective research laboratories, photography studios, and civil engineering designs—point to the varied artistic, architectural, scientific, and technological contexts that guided early cinema’s development.3

By examining the spaces and forms that influenced the Black Maria’s design, the films produced in the studio, and the studios and films that came after it, this chapter argues that cinema emerged as a key component of a broad reformation of the relationship between nature and technology in the late nineteenth century. Beginning with Lewis Mumford in the 1920s, historians of technology have argued that the turn of the twentieth century marked a new stage in the greatest technological revolution in history: the construction of an artificial world founded not simply on our domination and exploitation of nature through machines, but rather on nature’s outright replacement by human-built technological environments.4 The devices and materials undergirding this new technological world emerged from late-nineteenth-century research laboratories such as Edison’s. Here, the craft-shop model of collaborative labor and invention encouraged overlaps and intersections among new inventions that helped lead to the production of the broad technological systems that shaped industrial modernity.

Cinema should be understood as a significant component of that process. The film technologies that emerged from the laboratory would offer a powerful system of world-building of their own, with the studio as their spatial locus. At the Edison laboratory, the problem of inventing cinema became not simply a question of creating a camera or projector but also an architectural problem of producing the necessary space for capturing movement. The Black Maria was Dickson’s solution. The result went beyond mere motion capture; it also defined an aesthetic form and the conceptual frame for a modern type of technological space—film—that would be no less technological in its future studio and non-studio forms.

While the Black Maria may be the best example of the film studio’s direct link to the laboratory, the studios that followed should equally be understood as technological spaces, or as machines. From their origins, the first studios were designed to defy the dictates of day, night, weather, and location in order to frame the production of artificial environments. This framing produced a version of what Martin Heidegger described as “enframing”—the process by which technologies extract “the energies of nature” and place them on reserve.5 The Black Maria, this chapter argues, enframed sunlight as a raw material needed to activate the chemical processes for recording movement. Edison filmmakers such as Edwin S. Porter and James White used the studio as one key component of the basic apparatus for producing literal versions of Heidegger’s metaphoric “world picture”: films that set the world before the human subject and rendered it knowable as a series of moving images.6

THE BLACK MARIA: STUDIO, MACHINE, UNKNOWN FORM

The few existing images of the Black Maria may explain the tendency among observers, critics, and historians to disparage the studio’s “primitive,” “rudimentary” form, while variously describing it as a “dismal-looking affair” and a “rambling building of cheap construction.” In one of only three known photographs of the studio’s exterior (fig. 1.1), reportedly taken in 1903, the structure appears as a ramshackle hodgepodge of geometric forms, crudely cobbled together and ready, at any moment, to collapse into only so many odd building blocks and irregular detritus.

FIGURE 1.1 Black Maria, summer 1903. (Courtesy of U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park)

Within only a few years, the seldom-used and now-dilapidated building would indeed be demolished, perhaps taking its place, like so many provisional machines and outworn technological spaces, alongside the discarded railroad wheel posed in the photo’s foreground. Only a few years earlier, however, the studio was the center of Edison’s film production and a hive of laboratory activity. In its more than half a decade of use beginning in 1893, the studio framed the production of thousands of films featuring contemporary vaudeville stars, local performers, miscellaneous celebrities, and Edison lab employees.

Dickson developed the studio’s design in late 1892 as part of the laboratory’s preparations for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Edison hoped to feature a series of Kinetoscopes there, and Dickson recognized that a dedicated production space with good lighting would be necessary to furnish these machines with sufficient films.7 A team of laboratory staff, led by John Ott, one of the laboratory’s most skilled machinists, and several freelance carpenters assembled the studio according to Dickson’s design during the winter, completing the job in February for a total cost of $637.67.8 It was built of wood covered in tarpaper (a material typically used for waterproofing roofs) attached with tin nails, and extended approximately fifty feet in length and fifteen in width, with a height varying from seven to twenty-two feet (fig. 1.2).9

FIGURE 1.2 Black Maria, circa winter 1893–1894. (Courtesy of U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Thomas Edison National Historical Park)

Far from being primitive in form, the studio had a complex design for capturing sunlight, highlighting moving objects for the Kinetograph, and facilitating efficient film production by increasing the available working hours and providing consistent, specialized workspaces for shooting, developing, and processing films. Dickson placed the studio stage beneath two perpendicularly intersecting gabled roofs, the taller of which rose to twenty-two feet and could be opened on one side to admit sunlight. Behind the stage, the lower 18-foot roof covered the “black tunnel” that gives the Black Maria films their distinct black background. On the other side of the stage, just beyond the roof opening, Dickson added a 9 × 7 foot darkroom for loading and unloading film from the Kinetograph, which could be mounted on tracks running between the darkroom and the filming area. The entire structure was mounted on a central graphite pivot with wheels at each corner, perched on a circular track. Using two large boards extending from the center of either side, several workers could rotate the studio in order to adjust the angle of sunlight illuminating the stage through the open roof.

As performers and the press began to visit in 1893, the studio, initially referred to simply as the “revolving photograph building” or the “Kinetographic Theatre,” quickly acquired both a new moniker and a reputation for being an especially strange structure, even at the Edison laboratory. Lab personnel coined it the “Black Maria” after judging that the studio bore closest resemblance to police vehicles of the same name.10 For Dickson, the studio resembled a “medieval pirate-craft,” and its interior evoked images of dungeons, torture, and death.11 Likewise, Edison Company lawyer Frank Dyer recalled the studio’s “lugubrious interior,”12 and one press report noted that it “reminded everybody of a huge coffin.”13

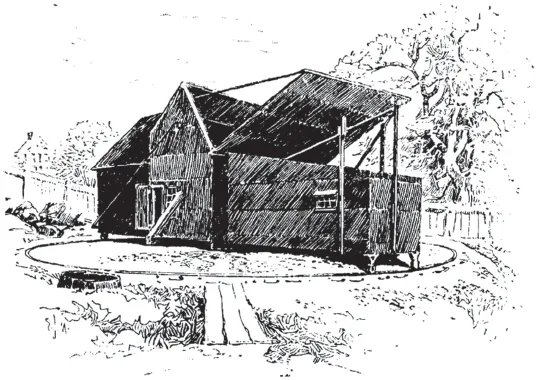

Contemporary illustrations such as Edwin J. Meeker’s ink drawing (fig. 1.3) for an 1894 Century Magazine article by Dickson and his sister, Antonia, must have reinforced such descriptions. In Meeker’s drawing, the studio appears slightly elongated, and the darkroom’s exaggerated length indeed helps evoke the shape of a casket. The lightly sketched, spare landscape stands in sharp contrast to the darkened studio’s imposing presence. Meeker’s shading lines on the building’s forward section parallel the open roof, creating a sense of movement into the interior, as if the studio might swallow elements of its surroundings.

FIGURE 1.3 “Exterior of Edison’s Kinetographic Theatre, Orange, N.J.” Ink drawing by Edwin J. Meeker, Century Magazine 48 (June 1894): 214.

In what might be read as a visual metaphor for the process by which modern technology, in Heidegger’s theory, extracts energy from nature, an adjacent tree dangles over the open roof, bending as if it were being sucked into the studio.14 To the left, a darkly shaded stump suggests both the Black Maria’s material origins and nature’s future fate at the Edison lab, where trees were just as likely to become picket fences, bridges, or studios. The wood-plank bridge in the immediate foreground further inscribes such an idea of progress into the image, both by offering a crude counterpart to the studio’s modernity and by recalling Dickson’s comparison of the studio to another modern nineteenth-century technology, the swinging river bridge.15

The uncertainty and imaginative creation expressed in Dickson’s and other witnesses’ early attempts to associate the new building with some familiar form suggests not so much the building’s inherent strangeness as the novelty of the film studio. While a more conservative observer could very well have described the Black Maria as a strange but not altogether unworldly pitched-roof house in need of windows and paint, its status as a film studio—a previously unknown entity—contributed to doubts about its form and function. Indeed, like the motion picture machines used in it, the studio represented a novel invention and an unfamiliar technology whose sources of inspiration and formal influence remained unclear. Contemporary observers did not have to look far, however, to find more precise models for the studio’s design, both in the Edison laboratory itself and in the technologies produced there. Like other contemporaneous sites of cinematic invention, the West Orange laboratory framed early cinema’s technological ontology. Within and according to the principles of these laboratories and workshops—the first “studios” of sorts—cinema’s inventors and first practitioners developed an idea of what cinema would become.

LABORATORIES, WORKSHOPS, ATELIERS—ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL IN THE FIRST “STUDIOS”

You can’t help but have noticed that Boulevard cafes aspire to become successors of the Faculté des science. Below the room where one drinks glasses of beer, there is a basement in which highly decorated gentlemen perform ...