![]()

![]()

One

HISTORIES OF CROSS-CULTURAL ENCOUNTER, ORIENTALISM, AND THE POLITICS OF SEXUALITY

Postcolonial archival work, in short, ought to restore to the science of colonialism its political significance in the current global setting. What would emerge out of such a reading is not a specialized erudite knowledge of Europe’s guilty past but the provoking rediscovery of new traces of the past today, a recognition that transforms belatedness into a politics of contemporaneity.

Ali Behdad, Belated Travelers1

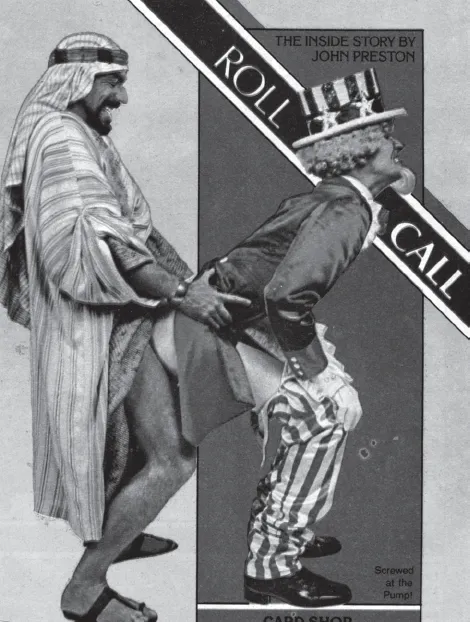

Uncle Sam getting “screwed at the pump” by an Arab sheik: it’s hard to think of a more sensationalist visual representation of East–West relations than the coupling depicted in a cartoon that appeared in the gay magazine Numbers in 1980, in which a hoary-headed Uncle Sam takes it up the rear from a robed Arab man who dominates him in gloating if not to say orgiastic triumph (fig. 1.1). Reflecting the defeatist mood of the United States during that year’s oil crisis as increasingly frustrated American drivers lined the blocks for hours waiting their turn at the gas pump, this illustration deploys a call to patriotism, xenophobic stereotyping, homophobia, and camp sensibility to articulate nothing less than a manifest national anxiety in which America’s loss of international clout is equated, tellingly, with an emasculating loss of phallic supremacy.

More than twenty years later, a similarly suspect mix of politics and sexuality appeared in an anonymously doctored photograph widely circulated on the Internet after the U.S. invasion of Iraq. In this image, a naked figure is shown sodomizing a donkey that stands placidly by a wire fence in a desert landscape. Now the butt of the joke is the sodomizer, given that the turbaned face attached to the scrawny man having sex with the donkey is that of Osama bin Laden (the online image is too small to reproduce successfully here, but the photograph can easily be found by googling the search phrase “osama bin donkey”).2 Rather than a symbol of foreign power overwhelming an emasculated United States, this depiction of sodomy denotes dehumanizing bestiality and, by association, the uncivilized, animalistic nature of America’s once “number one” terrorist—stereotypes belied by the sophisticated organizational apparatus that kept bin Laden out of the CIA’s reach for nearly a decade. Given the historical association between sodomy and bestiality as equivalent categories of sin, on the one hand,3 and between sodomy and Muslim men, on the other, this image of “bin Laden” is implicated in the xenophobia and homophobia that characterize the Numbers cartoon. Using sodomy to dehumanize bin Laden took yet another turn in a caricature that, as Jasbir K. Puar reports, appeared on posters across midtown Manhattan after 9/11. Here, the Empire State Building anally impales a turbaned bin Laden, accompanied by the legend, “The Empire Strikes Back … So you like skyscrapers, huh, bitch?”4 The penetrating phallus has returned to the service of the nation—even if, in an ironic twist escaping the artist’s intention, this reassertion of dominance depends on the participation of the United States in a symbolic act of male sodomy.5

FIGURE 1.1. Sodomy as political ammunition.

Unsigned cartoon in Numbers magazine (1980). Courtesy of Don Embinder, publisher.

Despite the cartoonish cast of such representations, these reflections of xenophobia, nationalism, and homophobia are sobering in their real-world implications and referents. Using aspersions of homosexuality as a political tool differentiating East and West takes a more prosaic, but nonetheless revealing, turn in a recent flare-up between Turkey and Greece. Trading insults is a typical part of the sports rivalry in these two nations. But when a YouTube video posted by Greek soccer enthusiasts accused the Turkish Republic’s founding father, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, of being homosexual, outraged Turks responded by reminding their neighbor of its reputation as the birthplace of pederasty. Meanwhile, the Turkish judiciary took the dramatic step of banning YouTube broadcasts.6 History, inevitably, fuels this dispute, given that Greece, the so-called birthplace of Western civilization, was in fact part of the Ottoman East from the fall of Athens in the mid-fifteenth century to its declaration of independence in 1821, and this period of Turkish rule (known in Greece as Tourkokratia) underlies the animosities that exist between the two countries to this day. In the light of this history, the YouTube name-calling exchange represents a fascinating return of the repressed, one in which charges of male homosexuality—who has “it,” and who doesn’t—become the trigger for a display of mutual xenophobia.

As this book demonstrates, these conjunctions are hardly unusual. In formats fictional and nonfictional, public and private, written and visual, generations of Anglo-Europeans since the opening of the Middle East to Western diplomacy and trade have recorded their impressions of the seemingly rampant exercise of sodomy and pederasty that haunts their imagined and actual encounters with its cultures, issuing in everything from shrill diatribes against this ungodly “vice” that separates heathens from the saved to poetic reveries in which male homoeroticism subtly insinuates itself as a temptation no longer to be resisted. The essence of any Orientalizing erotics lies in the projection of desires deemed unacceptable or forbidden at home onto a foreign terrain, in order to reencounter those desires, in the words of Walter G. Andrews and Mehmet Kalpakli, “at a safe distance in stories, gossip, and even the respectable garb of social science.”7 Sometimes, as in the case of what seems “like” homosexuality, that distance proves not to be so safe after all, dissolving the boundary between self and other and reconfiguring both in the process—or, conversely, revealing the extent to which that “other” already exists within the self, haunting its self-definitions.

This chapter historicizes these projections and perceptions of male homoerotic desire from a variety of facets. Their accretive force is designed to suggest a methodology of reading flexible enough to capture the nuances and complexities—discursive, political, psychological—that attend the homoerotic subtexts embedded in Orientalism and that make the cultural work that these iterations perform worth examining in the first place. I begin with a contrapuntal example of close reading, drawing on two seventeenth-century documents (one Ottoman and one English) in which male-male sexuality plays a central role in order to illustrate the unexpected congruences that result upon considering such documents in tandem. Building on this reading, the next two sections address the contributions this project hopes to make, the benefits of examining the homoerotics of Orientalism for our contemporary moment, and the legacy of Said’s theorizing of Orientalism as a discursive system of knowledge over the past three decades. The heart of the chapter lies in the fourth section, which traces recurring references to sodomy and pederasty in a vast number of European narratives about the Muslim world dating from the early modern period to the nineteenth century. Creating a bridge between this archival material and twentieth-century historical, socio-ethnographic, and sexological studies of homoeroticism in the Middle East, the final section analyzes the contradictions embedded in these Eurocentric speculations and, in contrast, begins to contextualize the social scripts and socio-communal codes that Muslim cultures have produced around issues of male homoerotic desire, practice, and love.

READING CONTRAPUNTALLY; TWO CAPTIVITY NARRATIVES

What story ensues when we read side by side two seemingly disparate seventeenth-century texts that just happen to situate sexuality between men at the juncture where myths of East and West collide? One English, the other Ottoman; one a didactic religious tract less than ten pages long, the other a flowery narrative poem of nearly 300 couplets: the first is an anonymous pamphlet published in London in 1676 (never reissued) and titled The True Narrative of a Wonderful Accident, Which Occur’d Upon the Execution of a Christian Slave at Aleppo in Turky; the second is the seventh tale or mesnevi of a book-length verse narrative by Ottoman poet Nev‘izade ‘Atayi completed in 1627. Despite their overt differences, the ideological objectives and sexual resonances of these two narratives illuminate each other—and in the process illuminate the history of sexuality—in ways that demonstrate what may be gleaned by venturing outside of disciplinary constraints and reading representations of the past contrapuntally.

The shorter, seemingly less complex A Wonderful Accident is an unabashed example of Christian propaganda, narrated in a sensationalist idiom aimed at titillating and horrifying its audience. In 1676 Turkish imperial ambitions were at their zenith: the Ottoman army had seized part of Poland; seven years later, it would lay siege to Vienna in its most audacious attempt to see all Europe submit to Ottoman control. Written under the shadow of this palpable threat, this cheaply produced document recounts the horrific fate a “handsome young French slave” suffers when subjected to Turkish male lust, figured as “that horrid and unnatural sin (too frequent with the Mahumetans) Sodomy.”8 While the trajectory that follows is typical of martyrdom narratives, replete with a miraculous apotheosis as its climax (the “wonderful accident” of the title), the tale is encased in a frame calculated to place the “unnatural sin[s]” of the Turks at as far a remove from English mores as possible: constructed as a letter addressed to an anonymous “Sir,” the unnamed English narrator doesn’t recount his own experience but retells a “history” that has, in turn, been told to him by merchants returning from Aleppo.9 On one level, the pamphlet’s framing device places the reader at five levels of remove from the narrated events, thereby establishing a moral as well as geographical gulf between its English audience and those brute desires to which “Mahumetans” are too often “addicted.” Likewise, the fact that the victim is French, rather than English, brings the horror home to Europe but strategically stops it short of leaping the English Channel. On another level, however, the narrator inadvertently begins to close that gap by directing doubtful readers to seek out the many “Turkey-Merchants” who frequent “Elford’s Coffee-House in George-yard in Lombard Street” whom, he avers, will “confirm the thing.” The contagious buzz of coffeehouse gossip keeps Turkish sodomy alive and well in the heart of London.

The “handsome” eighteen-year-old Christian slave (presumably captured from a merchant vessel by Turkish privateers10) has been left alone at his wealthy master’s home with the master’s steward. The latter Turk is one of those of his nationality “much addicted” to sodomy and, having had his “lustful Eyes” on the good-looking youth for some time, finds the moment propitious for executing his “Villa[i]nous design.” Failing to persuade the youth to “consent to his (more than Brutish) Devillish desires” with promises and flattery (2), the steward resorts to violence. However, the slave, virtuous Christian that he is, refuses to yield his chastity to such “Devillish” ploys; during the ensuing struggle the Turk dies; and the beset youth, anticipating the “Cruel and Tyrannical nature of the Turks” (3) upon discovery of this mishap, runs away in hopes of finding sanctuary in the city’s European enclave (where, incidentally, the Levant Company maintained its headquarters).

His attempt to escape, however, is stymied when he bumps into his master returning home, and, sure enough, he’s charged with murder of the steward. But in a reversal that momentarily dissolves the opposition between Europe and Other, the magistrate ...