![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Ruins of Utopia

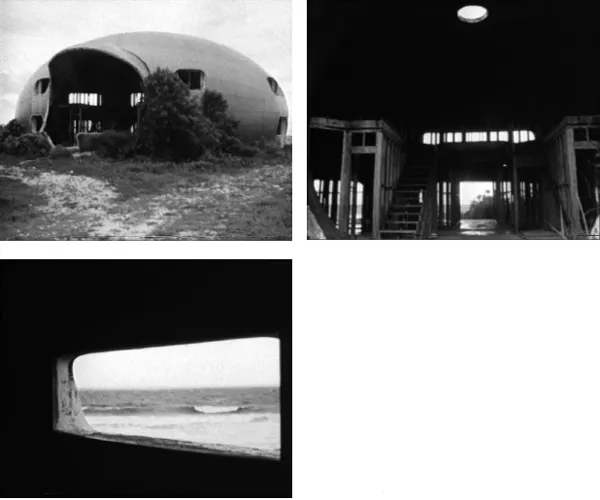

Is there any space, whether conceptual or practical, for thinking about utopia after the disasters of the twentieth century – a century that has given us two world wars, the military application of technology, the rise of totalitarian regimes, the Holocaust and the failure of the communist revolution? British-born, Berlin-based artist Tacita Dean’s Bubble House (1999) both poses and represents one response to this question. Shot in pristine 16mm, this seven-minute-long film explores the eccentric form of a dilapidated and unfinished construction that the artist found on the coast of Cayman Brac, a Caribbean island. Named ‘Bubble House’ for its strange oval shape, the ruin suggests simultaneously the breakdown of the utopian impulse in the twentieth century and its stubborn persistence in spite of its disastrous history. The derelict building was begun in the 1960s and never completed; it now lies abandoned in the middle of the jungle. Like many of Dean’s films, Bubble House has no characters and a minimal narrative; the film opens with a panoramic shot taken from the nearby road, from which we can see the house in the far background, hidden behind the overgrown scrub. Dark emerald greens and greyish whites are the most recurring colours of the film’s cinematography, while the sound is composed of the noise of heavy rain, gusting winds, violent thunderstorms and the crying of birds. The film then cuts to a closer view of the construction. The roof protrudes noticeably on one side of the building, where an enormous aperture opens the space of the house to the exterior. Finally, the camera moves into the interior, where skeletons of staircases and walls are shot against the glaring light of one of the windows. Strong beams of light penetrate the otherwise dark interior while the vivid sound of the storm and the ocean reverberates in the empty structure. After lingering on the interior for considerable time, the film ends with two other views of the building in its surroundings.

Figs. 1, 2, 3. Tacita Dean, Bubble House, 1999, 16mm colour, sound, 7 minutes (Courtesy Tacita Dean and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York)

Dean is less interested in uncovering the historical record regarding the run-down house than in transforming it into a mesmerisingly enchanted place. Reminiscent of 1960s structural cinema, Dean’s camerawork is enthralling: one of the longest shots in the film portrays the ocean as seen through one of the ruin’s imposing windows; waves are constantly rolling and dissolving into the sea to create a hypnotic flux and, at certain moments, the ocean seems to almost enter the interior of the building.1 The consequent visual and acoustic effects produce an epiphanic experience, as the house appears extraordinarily animated. The site significantly differs from the rest of the island. As the artist has remarked, Cayman Brac was an ‘absolutely unbearable, very claustrophobic, moneyed [place]’,2 rife with the ‘neat housing’ and the air-conditioned resorts of the ‘ideal holiday location’, a ‘tax heaven and a paradise for the rich’.3 Unlike the sealed, wealthy and polished architecture of elsewhere, the ruin is open to the exterior through gigantic rectangular windows, but it also appears as a self-enclosed, protective space, which might evoke the form of the maternal womb. With its enormous frontal opening, the Bubble House also recalls the shape of Thomas More’s famous imaginary island of Utopia. In his well-known book of the same title, More described the imaginary and perfect land as a sort of crescent with its tips divided by a strait, creating a vast circular standing pool.4 Like More’s Utopia, the boundaries of the Bubble House are porous to the outside yet entirely controlled from within.

An aesthetics of ruins is a trademark of Dean’s practice. Destitute architectural constructions, discarded films and outmoded technologies are the subjects of many of her projects. Dean has declared to be interested in ‘places of disrepair’ and in ‘things which do not sit very easily in their own time’.5 She has filmed the rotting remains of the Teignmouth Electron, a trimaran used by a daring British sailor who died during a solo race across the world (Teignmouth Electron, 1999); an outmoded and discarded sound receiver in the south of England devised during World War I (Sound Mirrors, 1999); and a government building opened in 1976 in former East Berlin serving as the seat of the German Democratic Republic parliament (Palast, 2004). These forlorn objects never fulfilled the promise of security, happiness and emancipation that they were supposed to deliver: beached on the scrub of a Caribbean island, the Teignmouth Electron is the symbol of the optimism of the 1960s – ‘a time of exploration, of moon travel and experimentation, of pushing the limits of human experience’ – but also a reminder of the tragic death of the boat’s owner;6 the futuristic sound mirrors turned out to be a very flawed technology, unable to guarantee the security of the southern England coast, and were therefore abandoned; the Palace of the Republic in East Berlin became a monument to repression and surveillance, the evidence of how quickly the communist utopia turned into dystopia. Yet Dean’s beautiful camerawork transforms these places into sites of difference, flux and becoming.

Importantly, Dean was far from alone in exploring the ruins of failed utopian projects. Between 1998 and 2008 artists gave us experimental documentary films and photo-essays devoted to abandoned radical communes, tragic heroic journeys to the North Pole, the splendid past of industrialism in Detroit or the Soviet Union, modernist architecture by Le Corbusier or Jean Prouvé, and a number of works about unsuccessful nineteenth-century experiments with cinematic technologies. Contemporary artists’ fascination for ruins is hardly new: an aesthetics of ruins dominated late neoclassicism and early romanticism (e.g. in the etchings of Giovan Battista Piranesi), and, although in a much more deconstructive and ironic mode, this fascination was also significantly manifest in the 1960s land art (e.g. the sculptural work of Robert Smithson).7 Yet an aesthetic of ruins with a distinctive character of its own is again pervasive – enough so as to be considered a tendency in its own right. If the figure of the ruin is a trope of ‘the reflexivity of a culture that interrogates its own becoming’, what does this recent obsession with the sites of failed utopian projects tell us about our current condition?8 Contemporary artists’ fascination for ruins interests me because it is so powerfully and uniquely appropriate to our historical moment – which is to say, powerfully and uniquely troubling.

We could view this desire to revisit failed utopian projects in the past as symptomatic of the exhaustion of the utopian impulse after the disasters of the twentieth century. The century has generated a plethora of dystopian literature and cinema, from Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) and the Wachowskis’ Matrix trilogy (1999, 2003, 2003). Likewise, the past decade has offered plenty of inspiration for the production of apocalyptic scenarios: opening with the collapse of the Twin Towers in New York, continual wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere in the Middle East, macro-economic crises and the acceleration of global warming, the twenty-first century presents sufficient warnings against unbridled optimism. The times of utopia, we might conclude, are long gone, and artists’ interest in ruins melancholically laments the loss of the idea of the future as a hopeful modern vision of progress. In light of this crisis, the recent ‘nostalgia for utopia’ may appear distinctly untimely insofar as we might most readily conceive ourselves as being situated in a historical period marked by a post-utopian outlook. But the crisis of utopia is also philosophical. Because of its complicity with fascism, Nazism and Stalinism, over the past fifty years the concept of utopia itself has been vehemently attacked by thinkers of different provenance. For Martin Jay, Judith Shklar, Étienne Balibar and Gianni Vattimo – to mention just a few prominent theorists – utopia expresses the dangerous desire for a perfect, controlled and pure society; it is also the residue of a classic metaphysical tradition that betrays an elitist longing for order and purity. As Martin Jay once wrote, utopia is ‘a sure-fire recipe for totalitarian domination’.9 For Francois Lyotard, the classical utopia in the tradition of Thomas More is a ‘grand narrative’ and therefore naturally under suspicion of totalitarianism; likewise, for Gianni Vattimo the utopia of progress at the centre of the philosophy of the Enlightenment is a dangerous ‘will to system’, a ‘mix of social discipline, repression, calculative objectivization and the technological application of science’.10 In light of this trenchant critique, should we assess contemporary artists’ tendency to revisit utopian dreams of the past as symptomatic of a reactionary desire for order and conformity?

I would say ‘no’. In fact, through the appropriation of modern ruins, most contemporary artists construct utopia as the image of flux, becoming and disruption of pre-existing structures and codified meanings. Rather than belonging to a crepuscular and romantic world of death and loss, contemporary photographers’ and filmmakers’ ruins are often framed as sites that anticipate the becoming of new orderings and forms. Geographer Tim Edensor has well described the utopian impulse underpinning this aesthetic of ruins. ‘While ruins always constitute an allegorical embodiment of a past,’ he has remarked, ‘they also gesture towards the present and the future as temporal frames [and] help to conjure up critiques of present arrangements and potential futures.’11 It is precisely the challenge of reinventing the seemingly exhausted legacy of utopian thought that contemporary photographers and filmmakers take up.

However, these artists’ ruins are invested with extraordinary ambiguity and even ambivalence, as they can be read as both dystopian and utopian. On the one hand, these artistic projects convey the notion that an alternative to our present world is possible and should be sought after; on the other, they also represent utopia as a non-place or a fiction, that is, as an always impossible model which will never be achieved due to society’s inherent inability to overcome its own authoritarian tendencies and contradictions. As we will see, their belief in the necessity of imagining alternative modes of living is accompanied by a dormant scepticism about societies’ potential to realise utopian blueprints and transcend the present.

Also animated by a latent scepticism about utopian thought is Michel Foucault’s notion of heterotopia. First introduced in The Order of Things in 1966, then re-elaborated in a lecture for architects in 1967 and finally published as a text in 1984, this concept expresses many of the doubts and anxieties characterising thought on utopia in the aftermath of World War II.12 Reading contemporary artists’ fascination for ruins through the shorthand of Foucault’s heterotopia, I would argue, enables us to capture the inherent ambivalence and limitations of recent experimental documentary practices.

Foucault’s scepticism about utopia stemmed from his distrust of any metaphysical or orthodox system of knowledge. For him, any discussion of imaginary perfect societies deflected attention from the here and now; utopian thought entails a prescriptive vision of the future based on a set of fixed ideal norms: positing truth as something fixed once and for all, utopian thought may lead to authoritarianism and the repression of dissent. ‘For a rather long period, people have asked me to tell them what will happen and give them a program for the future’, the philosopher declared; ‘we know very well that, even with the best intentions, those programs become a tool, an instrument of oppression. Rousseau, a lover of freedom, was used in the French Revolution to build up a model of social oppression. Marx would be horrified by Stalinism and Leninism.’13 Foucault’s suspicion of utopia also emerges in his 1967 lecture at the Circle d’Études Architecturales (Circle of Architectural Studies) in Paris, wherein he deployed the term ‘heterotopia’. While utopias are purely metaphysical and imaginary spaces, heterotopias are real ‘emplacements’. Heterotopias are far from perfect sites: indeed, many of the examples provided by Foucault – prisons, missionary colonies, brothels, cemeteries, touristic resorts – cannot be said to represent ideals of happiness and freedom. Nevertheless, heterotopias are interesting in that they interrupt the apparent continuity and normality of everyday space. Etymologically, the word denotes the contraction of ‘hetero’ (another or different) and ‘topos’ (place), suggesting that heterotopias contain certain elements of alterity that distinguish them from the other remaining spaces.

There are also, and this probably in all culture, in all civilization, real places, effective places, places that are written into the institution of society itself, and that are a sort of counter-emplacements, a sort of effectively realized utopias in which the real emplacements, all the other real emplacements that can be found within culture, are simultaneously represented, contested and inverted; a kind of places that are outside all places, even though they are actually localizable. Since these places are absolutely other than all the emplacements that they reflect, and of which they speak, I shall call them, by way of contrast to utopias, heterotopias.14

What made heterotopias a relevant object of study, for Foucault, was their imbrication with the everyday. Heterotopias are not radically other than the spaces of ordinary life: that is, they are not sites of the complete erasure of the normative. But neither are they absolutely negative and nightmarish historical configurations. Foucault concluded his lecture with an evocative and adventurous image of a sixteenth-century boat crossing the ocean to explore new territories. ‘The ship is the heterotopia par excellence’, he concl...