![]()

1

THE BIG PICTURE

Philosophy After the Apollo Missions

Men’s conception of themselves and of each other has always depended on their notion of the earth.

—ARCHIBALD MACLEISH, “RIDERS ON EARTH TOGETHER, BROTHERS IN ETERNAL COLD”

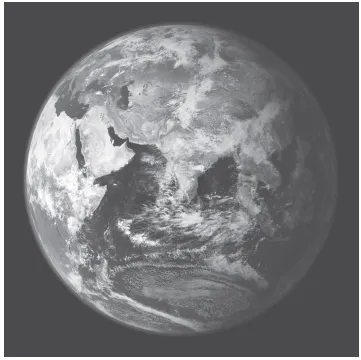

FIGURE 1.1. Blue Marble. Image by Reto Stöckli, rendered by Robert Simmon. Based on data from the MODIS Science Team

The spectacular images from the 1968 and 1972 Apollo missions to the moon, Earthrise and Blue Marble, are the most disseminated photographs in history.1 Indeed, Blue Marble, the most requested photograph from NASA, is the last photograph of the planet taken from outside Earth’s atmosphere.2

Whereas Earthrise shows the earth rising over the moon, with elliptical fragments of each (the moon is in the foreground, a stark contrast from the blue and white earth in the background), the later image, Blue Marble, is the first photograph of the “whole” earth, round with intense blues and swirling white clouds so textured and rich that it conjures the three-dimensional sphere.

Even more than previous photographs of Earth, the high definition of Blue Marble and the quality of the photograph make it spellbinding. Set against the pitch-black darkness of space that surrounds it, the earth takes up almost the entire frame. Unlike in Earthrise, in Blue Marble the earth does not look tiny or partial, but whole and grand. Both of these photos from Apollo missions (8 and 17) were immediately met by surprise, along with excited exclamations about the silent beauty of this “blue marble,” this “pale blue dot,” this “island earth.”3

FIGURE 1.2. Earthrise. Image Credit: NASA

In the frozen depths of the cold war, and over a decade after the Soviets launched the first satellite to orbit Earth, Sputnik, these images were framed by rhetoric about the “unity of mankind” floating together on a “lonely” planet. At the same time as vowing to win the space race with the Soviet Union, the United States wrapped the Apollo missions in transnational discourse of representing all of “mankind.” Indeed, these now iconic images ignited an array of seemingly contradictory reactions. Seeing Earth from space generated new discussions of the fragile planet, lonely and unique, in need of protection. These tendencies gave birth to the environmental movement. At the same time, the Apollo missions spawned movements to unite the planet through technology. Heralded as man’s greatest triumph, the moon missions lead to a flurry of speculation on not just the technological mastery of the world, or of the planet, but also of the universe. While seeing Earth from space caused some to wax poetic about Earth as our only home, it led others to imagine life off-world on other planets. While aimed at the moon, these missions brought the Earth into focus as never before.

The photographs of Earth from space sparked movements aimed at “conquering” our home planet just as we had now “conquered” space. Indeed, critics of these early ventures into space asked why we were concentrating so many resources on the moon when we had plenty of problems here on Earth, not the least of which was the threat of nuclear war (Time 1969). The Apollo missions were a direct outgrowth of this threat in terms not only of the significance of the race to space but also rocket technologies, which originated with military developments in World War II. The atom bombs dropped in Japan in 1945 heralded the nuclear age with the threat of total annihilation. And the development of rockets by both the United States and Germany as part of military strategies in WWII gave rise to rockets launched into space by the USSR and USA in decades that followed. Indeed, the U.S. recruited German scientists to work with NASA.

Within a decade, we had gone from world war and the threat of genocide of an entire people, to the possibility of nuclear war and the threat of annihilation of the entire human race. And, within another decade or two (with Sputnik and then the Lunar Orbiter and Apollo missions and photographs of Earth from space), the world gave way to the planetary and the global. Following Heidegger, we might call this “the globalization of the world picture.”4 Indeed, upon seeing the Earth from space, Astronaut Frank Borman exclaimed, “Oh my God! Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, that is pretty! You got a colour film, Jim?” And William Anders responded, “Hand me that roll of colour quick.”5 The Earth had become a picture even before the photo was taken. Within a few short decades, the rocket science used by the military in WWII had given rise to the globalism that we have inherited today. From global telecommunications such as cell phones and Internet to global environmental movements, the Apollo missions moved us from thinking about a world at war to thinking about the unification of the entire globe. If, after seeing Earthrise, as Archibald MacLeish claims, “Men’s conception of themselves and of each other has always depended on their notion of the earth,” then, in order to understand ourselves and our interactions with other earthlings we need to ponder the meaning of earth and globe and the place of human and nonhuman worlds in relation to them.

FROM GLOBALIZATION TO EARTH ETHICS

In this book, we explore some philosophical reflections on earth and world, particularly insofar as they relate to the globe, and thereby to globalization, to begin to develop an ethics of earth, or earth ethics. Starting with Immanuel Kant, we follow a path of thinking our relations to each other through our relation to the earth. We move from Kant’s politics based on the fact that we share the limited surface of the earth, through Hannah Arendt’s and Martin Heidegger’s warnings that by leaving the surface of the earth we endanger not only politics but also our very being as human beings, to Jacques Derrida’s last meditations on the singular world of each human being. This trajectory leads us from Kant’s universal laws, which apply to every human being equally because we share the surface of the earth, through Arendt’s insistence on a plurality of worlds constituted through relationships between people and cultures, and Heidegger’s thoroughly relational account of world and earth as native ground, to Derrida’s radical claim that each singular human being—perhaps each singular living being—constitutes not only a world but also the world. In all of these thinkers we find a resistance to world citizenship and to globalization, even as some of them embrace different forms of cosmopolitanism. And yet, in their work we also find the resources to think the earth against the global in the hope of returning ethics to the earth. The very meaning of earth and world hang in the balance. So too does our relationship to earth, world, and to other earthlings.

The guiding question that motivates this book is: How can we share the earth with those with whom we do not even share a world? The answer to this question is crucial in terms of figuring out whether there is any chance for cosmopolitan peace through, rather than against, both cultural diversity and the biodiversity of the planet. Can we imagine an ethics and politics of the earth that is not totalizing and homogenizing? Can we develop earth ethics and politics that embrace otherness and difference rather than co-opting them to take advantage of a global market? How can we avoid the dangers of globalization while continuing to value cosmopolitanism? Following the trajectory from Kant’s universalism to Derrida’s radical singularity, we explore different conceptions of earth and world in order to develop an ethics grounded on the earth. Inspired by Kant’s suggestion that political right is founded on the limited surface of the earth, and Derrida’s suggestion that each singular being is not only a world but also the world, we can articulate an ethics of sharing the earth even when we do not share a world. This earth ethics is based on our shared cohabitation of our earthly home. Building on insights from Kant, Arendt, Heidegger, and Derrida, we conclude with an ethics of earth that is formed through tensions between politics as the sphere of universals and ethics as the sphere of the singular, tensions between world and earth, or what Heidegger calls “strife” between the two. Our ambivalent place on earth is signaled in that tension. The tension between politics and ethics, world and earth, resonates with the contradictory reactions to the first images of earth from space, urges to master along with humility, urges to flee along with the urgent desire for home. Acknowledging our ambivalence toward earth and world may be the first step in accepting that, in spite of the fact that we cannot predict or control either of them, we are responsible for both.

What we learn from Kant is that public right demands a universal principle of hospitality based on the limited surface of the earth. Although Kant limits hospitality to the right of visitation, still the “original common possession” of the earth’s surface becomes the basis for all political rights. Taken to its logical limits, Kant’s suggestion that political right is grounded on the earth as common possession undermines private property. In addition, the clear limit that Kant delineates between politics and morals begins to blur. What happens, then, when we start with Kant’s insights into the connection between politics and the earth and extend them to ethics? Here, Kant’s remarks on hospitality become the basis for an ethics of the inhospitable hospitality of the earth. Derrida famously extends Kant’s hospitality to its limit in unconditional hospitality to the point that we can no longer defend individualism or nationalism—indeed, to the point where we can no longer distinguish between host and guest, hospitality and hostility.6 Arendt too extends Kant’s notion of cosmopolitan hospitality to ground the always shifting “right to have rights,” which takes us beyond nationalism and toward our shared coexistence and cohabitation of both earth and world.7 Although Kant is clear that cosmopolitanism is a public or political right and not a moral one, he also insists on harmony between morals and politics.8 Contemporary criticisms of Enlightenment universalism, however, have reopened the split between morals and politics. Or, perhaps more to the point, both morals and politics are seen as at odds with ethics. If morality and political rights are necessarily universal, how can they account for singularity and the uniqueness of each individual? Derrida, among others, has tried to reformulate Kant’s principles of hospitality and cosmopolitanism in order to take into consideration the singularity of each person, even of each living being.9 The question, then, is: Can we negotiate between moral universalism and ethical particularism? Following Kant, Arendt, and Derrida, we must grapple with this tension between universal and particular, which sometimes shows up as a tension between nationalism and cosmopolitanism.

In this vein, Arendt struggles with the tension between national rights and human rights. While she embraces the plurality and unpredictability of the human condition, she insists on the necessity and priority of state rights over generic human rights. She argues that the notion of human rights reduces the human being to its species, like an animal, and does not have the force of any law behind it. Unlike rights guaranteed by sovereign states, human rights come with no such guarantee. While she allows for international laws that might provide such protection for stateless peoples, she also argues in favor of state citizenship and reminds us of the importance of membership in nation states, at least in a world where international law does not provide adequate protections for stateless peoples.10 The Apollo missions with their America First rhetoric of winning the cold war along side their transnational rhetoric of goodwill to all mankind are emblematic of this tension between nationalism and cosmopolitanism.

What we learn from Arendt is that politics is not primarily a matter of law, nor of hospitality per se, but rather it is based on the plurality of our cohabitation of both earth and world, a plurality through which we can and must create equality in the face of nearly infinite diversity. Arendt’s distinction between earth and world provides important resources for rethinking Kant’s notions of public and private right, the tension between morals and politics, and the notions of common possession and private property, especially in relation to war. For Kant, war is the result of the fact that we share the limited surface of the earth, and yet this same fact can and should eventually lead to perpetual peace. For Arendt, the plurality and diversity of our coexistence on earth leads to war; yet for the sake of politics, and ultimately for the sake of the endurance of human worlds, war must be limited. Arendt imagines a plurality of worlds formed through human interaction and relationships. While in some sense these worlds are of our choosing, in another sense they are radically unchosen. We are born into a world, worlds, and the world. Moreover, as she tells Eichmann, none of us has the right to choose with whom to share the surface of the earth. The unchosen nature of our earthly cohabitation gives rise not only to political obligations but also to ethical ones.

And yet, as we learn from Heidegger, the givenness of our inheritance must be continually taken up as an issue for the sake of the future of each individual and each people. While it is true that we are born into a world that we do not choose and that the unchosen character of our earthly cohabitation brings with it plurality, diversity, unpredictability, and promise, in order to become properly thought it must be interpreted and reinterpreted. Going beyond Heidegger, we could say that the unchosen nature of our earthly habitation and cohabitation must be taken up in order to become properly political and ethical. In other words, the givenness of inhabitation and cohabitation is not enough in itself to ensure that we act ethically or extend political rights toward other earthlings or the earth. Going beyond merely sharing the earth’s limited surface or the plurality of cohabitation, Heidegger adds profound relationality that makes every inhabitant fundamentally constituted through its relation to its environment. This interrelationality is not just the result of earthly ecosystems that sustain the life of each individual and each species. Rather, for Heidegger, this interrelationality operates at the ontological level whereby the very being of each individual and each species comes into being through relationships and relationality. With Heidegger, we get a sense of what it means to cohabit the earth as a dynamic of buzzing, flowing, raging, blowing, thanking, thinking, dwelling, and warring. If for Kant and Arendt our relations to the earth and to the world ground political right and politics itself, for Heidegger our relations to earth and world are not only constitutive of our very being but also of the ethos in which we live, all of us together in strife and wonder, cohabitants of earth. Following Heidegger, we can begin to imagine sharing the earth, even if we do not share a world. But, moving beyond Heidegger, we can begin to articulate an ethics of earth based on this sharing and not sharing.

What we learn from Derrida’s last seminar is that we both do and do not share the world. Emphasizing the profound singularity of each being—not just human beings—Derrida claims that with each one’s death the world is destroyed. This radical claim evokes a sense of urgency in relation to ethics and politics. Reformulating the tension between ethics and politics supposedly resolved by Kant, Derrida embraces the impossible intersection of ethics and politics, of the demand to respond to the singularity of each and the demand for justice for all. Derrida takes us beyond Kant’s notion of universal conditional hospitality to singular unconditional hospitality in the face of the absence of the world, particularly the world of moral calculation. This incalculable obligation to others—even the ones whom we may not recognize—challenges all political pluralities and notions of “peoples” in whose names “we” act. Derrida’s analysis brings to the fore the tension between ethical obligations that take us beyond calculation or universal principles and political obligations that necessitate calculation and universal principles. Emphasizing the radical singularity of each living being, in his last seminar Derrida employs the figure of an island. The island connotes isolation, even loneliness, cut off from civilization. Each singular life is an island cut off from all others. But even Robinson Crusoe on his desert island is not alone. The desert or deserted island is an illusion, a fantasy of autonomy and self-sufficiency. The ethical obligation that stems from the singularity of each living being is not Robinson Crusoe’s solipsistic delusion of mastery or control over himself or the plants, animals, and, ultimately, other humans that both share and do not share that island. On the one hand, Derrida insists that we do not share the world and that each singular being is a world unto itself, not just a world, but the world. On the other hand, and at the same time, we are radically dependent on others for our sense of ourselves as autonomous and self-sufficient, illusions that come to us through worldly apparatuses. We both do and do not share the world. With Derrida we get a sense of ethical urgency that we must return from the world to the earth. Even when the world is gone, the earth remains. Even if we do not share a world, we do share the earth. Moving from Kant’s political right founded on the limited surface of the earth, through Arendt’s plurality of worlds, and Heidegger’s profoundly relational account of earth and world, to Derrida’s ethics that begins when the world is gone, these chapters return earth to world and thereby ground ethics on the earth.

This book brings the urgency and responsibility of ethical obligation together with a sense of home or habitat as belonging to a community conceived as ecosystem and ultimately as belonging to the earth. By emphasizing the radical relationality of each living being, together with our shared but singular bond to the earth, the island no longer appears deserted or isolated, but rather in...