eBook - ePub

They Live

About this book

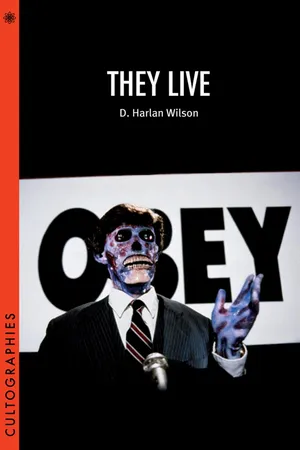

Born out of the cultural flamboyance and anxiety of the 1980s, They Live (1988) is a hallmark of John Carpenter's singular canon, combining the aesthetics of multiple genres and leveling an attack against the politics of Reaganism and the Cold War. The decision to cast the professional wrestler "Rowdy" Roddy Piper as his protagonist gave Carpenter the additional means to comment on the hypermasculine attitudes and codes indicative of the era. This study traces the development of They Live from its comic book roots to its legacy as a cult masterpiece while evaluating the film in light of the paranoid/postmodern theory that matured in the decidedly "Big 80s." Directed by a reluctant auteur, the film is examined as a complex work of metafiction that calls attention to the nature of cinematic production and reception as well as the dynamics of the cult landscape.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Film & Video1

THE CULT OF THE EIGHTIES

REAGANISM

The 1980s began as a hopeful period in the United States. Americans anticipated a return to the romanticised prosperity and ‘moral values’ of the 1950s that were trampled during the 1960s and 1970s. Stephen Feinstein explains:

The decade of the 1980s in the United States was a very different time.…The social upheavals in the 1960s brought about by the Vietnam War and opposition to it continued into the 1970s. Americans in the 1970s also witnessed the sorry spectacle of the Watergate scandal and President Richard Nixon’s resignation from office. And the 1970s ended with the humiliating episode of Americans being held hostage in Iran. By 1980, it was time for a change. Americans were tired of political protests. They were eager to feel good about themselves and their country again. Sensing their mood, Ronald Reagan campaigned for president on the theme of renewing good feelings about America. (2006: 5)

These feelings belonged mainly to right-wing conservatives for whom Reagan functioned as the ultimate posterboy, if not saviour. ‘For those happily on the right, the election of Reagan was evidence not that the next stage of decline had been reached but the point at which the liberal sixties might finally be expunged from national memory’ (Thompson 2007: 9). Reagan implied such a turnaround in his physical stature as much as his ideology, policies and personal history. With wisened good looks, thick, immaculately groomed hair and a confident white smile, all set atop a dark, broad-shouldered, conservatively tailored two-piece suit, he conveyed an image of entrepreneurial masculinity – strong, wealthy, patriarchal, capable of guiding the nation to utopia. Sometimes he swapped the suit for jeans, a denim shirt, cowboy hat and boots, a fashion statement that connected him more intimately with American history and the wilderness that men dressed like him colonised and ‘conquered’.

Hollywood stardom further reified Reagan’s American-made image. Beginning in the late 1930s, he appeared in scores of films and television shows before turning to politics and becoming governor of California in 1967 As a child watching his State of the Union addresses – or rather, watching my parents watch the addresses – I knew he had been a famous actor. But my only frame of reference was Bedtime for Bonzo (1951), a comedy where Reagan’s character attempts to educate a chimpanzee using 1950s child-rearing methods in order to prove that nurture, not nature, is what constructs identity. I don’t recall seeing the film. I have vivid memories of media imagery featuring Reagan with a monkey, imagery that may have been circulated by democrats in order to undermine him, or at least make him look funny, during his two presidential campaigns. Notwithstanding Bedtime for Bonzo, the actor-cum-politician’s celebrity status enhanced his appeal, fuelled by the pathological rigor of American image-culture. ‘Reagan’s presidency [was] the natural political counterpart to an eighties culture driven, and dominated, by the production and circulation of the image’ (Thompson 2007: 4–5). Reagan’s ‘celebridency’ was advanced even more by ‘a use of cinematic references and clichés in order to secure his political legitimacy’ (Thompson 2007: 99) – a curious case of rhetoric constituting image.

The president’s religious beliefs coincided with his economic policies. Bourgeois, Christian, white, right-wing and republican – much like George W. Bush in the 2000s – Reagan favoured the rich, affiliated himself with neo-Christian morality and pitted America against a foreign nemesis, cultivating the notion that the nemesis would soon infect and annihilate America ideologically, economically and actually.1 Taking all of these factors into consideration, the analogy between Reaganism and They Live is overt and resolute; without this president, I seriously doubt the film ever would have been made, at least in its current form as a critique of class divisions and capitalist power. If nothing else, the aliens represent what Kenneth Jurkiewicz has referred to as ‘the implacable forces of rampant, merciless Reaganomics’ (1990: 35). While this is perhaps the most important cultural signifier in They Live, the 1980s reflects a much wider spectrum of influence.

BIG HAIR

In the twenty-first century, the phenomenon of Big Hair is often ‘blamed’ on the 1980s. But it has recurred as an intoxicating vogue for centuries. Consider the fashion craze in the seventeenth century sparked by Louis XIV of France, who began to wear loud, lavish wigs to conceal the spectre of impending baldness (see Kwass 2006: 642). In the next century, French maîtresse-en-titre Madame de Pompadour gave life to the notoriously tall hairdo of the same name. And later, in the nineteenth century, American freakshow magnate P. T. Barnum turned Big Hair into literal spectacle with his ‘Circassian Beauties’, orientalised women made to look foreign and exotic by flaunting great wigs (see Thomson 1996: 249–50)

Los Angeles hair metal band Nitro outfitted in signature Jurassic bouffants.

Big Hair holds a privileged position in postmodern memory, however, and unlike these localised examples, its thoroughbred emergence in the 1980s denotes a widespread social and cultural formation. For me, it symbolises the colourful modes of excess and abandon that distinguished the period, ranging from Reagan’s socioeconomic policies to, say, the antics of rockstars (and rockstar wannabes) as depicted in The Decline of Western Civilization, Part II: The Metal Years (1988). Shot between 1986 and 1988 by Penelope Spheeris and released the same year as They Live, Big Hair abounds in this documentary of the Los Angeles glam-rock scene and its culture of reckless substance abuse, idiotic delusions of grandeur, and rampant egomania and squandering. Of course, such behaviour – and the hair that signified it – was not limited to Los Angeles. Nor was it limited to music scenes.

EXCESS

American excess became a moral obligation in the financial world, leading up to the stock market crash of 1987 Prior to the 1980s, ‘US stock trading was in a state of depression’ yet ‘between 1980 and 1988, 25,000 merger and acquisition deals were completed, worth a total of $2 trillion’ (Thompson 2007: 10, 11). Truly this phase is enframed by the guiding proverb of arbitrageur Gordon Gecko in Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987): ‘Greed is good.’ But reservoirs can only hold so much water, and eventually they go dry. A hearty disavowal of reality thus authorised the fiscal life of 1980s America, particularly among the wealthy, who were empowered/deluded by Reagan’s ‘no-holds-barred form of capitalism’ (Boozer 2007: 168). This mindset led to a number of economic woes. Inflation spiked early in the decade, setting the scene for the savings and loan scandal and an engorging national debt, both of which reached a climax at the end of the decade.2 These instances of pecuniary Big Hair widened the gap between rich and poor, inciting a kind of Marxist sentiment in the latter. This sentiment manifests palpably in They Live. The film endorses the call-to-arms of the ‘Communist Manifesto’: proletarians must rise against and quash their bourgeois masters with an eye to accomplishing class equality in the not-too-distant future. Violence paves the way to class equality.

Nada is a symbolic prole who, in the end, uses violence to single-handedly overthrow the alien bourgeois capitalists by exposing them for what they are. More specifically, he uses the force of his masculine body to expose their grotesque, inhuman bodies and incite mass hatred for them. Ideology stems from the flesh.

MASCULINITY AND THE BODY

Big Hair is a telling extension of the body. An even more resonant symbol for this sort of cultural hyperbole is the body itself, especially in media representation and cinema, where an excessive masculinity rapidly came to prominence. Any form of excess produced by the human subject is a compensatory effect of some traumatic kernel; when threatened, masculinity bucks and flares, vying to reassert power and control in the social matrix. Constance Penley and Sharon Willis argue that masculinity is ‘both theoretically and historically troubled’, and in the 1980s, ‘under the pressure of feminism and gay politics, and as a result of the demands of advanced capitalism for new kinds of workers, men [were] being asked to respond as men in new and different ways’ (1988: 4–5). Coupled with the imminent threat of Soviet takeover and nuclear disaster, these crises of class and gender spawned new modes of action and representation for maleness, modes that took shape on the growing variety of data screens that increasingly defined the daily lives of urban and suburban Americans.

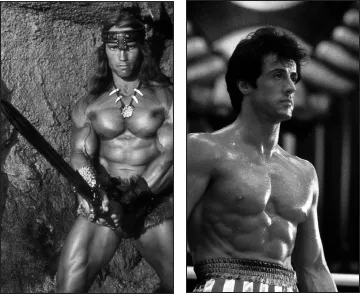

In cinema, the epitome of the übermasculinised body surfaced in the audaciously muscled action heroes portrayed by Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, movie stars who dominated the Hollywood blockbuster market. Prior to becoming an actor, Schwarzenegger almost single-handedly popularised the sport of bodybuilding; the culmination of his rise to fame can be seen in Pumping Iron (1977), a documentary of the 1975 Mr. Olympia and Mr. Universe contests. Thereafter he turned to acting, and just a few years later, he commanded the science fiction and fantasy genres with films like Conan the Barbarian (1982), The Terminator (1984), Predator (1987) and The Running Man (1987). Stallone appeared in action-packed cop, war and boxing dramas, most prominently the Rambo and Rocky franchises. The religiously glossy, overinflated, supersculpted physiques of each actor became fetishistic objects of desire – ironic silage for the male gaze, which had formerly eroticised the female cinematic body. Brian Caldwell writes:

Rock-hard insignias of Hope under the threat of phallic apocalypse.

Schwarzenegger’s body has…been described by one critic as ‘a condom stuffed with walnuts’, whereas Stallone…has been referred to as Fenimore Cooper’s ‘leatherstocking on steroids’. More significantly in terms of filmic representation, Gaylyn Studlar and David Desser refer to Stallone’s ‘glistening hypermasculinity’ as John Rambo and note how this ‘emphasized in the kind of languid camera movements and fetishizing close-up usually reserved for ‘female flashdancers’. (1996: 134)

In this era of Big Hair, Big Money and, ultimately, Big Fear and Paranoia, the male gaze turned inward, onto the male form, jacking it into phallic spectacle. Desire shifted from the sumptuous feminine (as exhibited by actresses such as Brigitte Bardot, Natalie Wood and Farrah Fawcett) to the Stallone/Schwarzenegger monster-hero – monstrous because of its hyperreal stature (made possible by anabolic steroids and human growth hormones3), heroic because of its infliction of violence upon terrorist forces.

By way of image and brutality, Stallone/Schwarzenegger assuaged a national anxiety incited by Reagan’s Cold War America. Rocky IV (1985) emboldens this dynamic. Shot midway through Reagan’s presidential career during the height of the Cold War, the film tells a clear-cut tale of good and evil. Stallone-Rocky represents the adamant, unshakable and moral (if dull-witted) American subject. Equally muscled and gleaming in the ring, Dolph Lundgren plays Ivan Drago, metaphor for the machinic, soulless, Orwellian Russian subject. Any critique of Reaganism is veiled at best; the simplistic narrative fails to problematise either half of the good/evil binary. Still, the film serves its purpose: not only does Rocky defeat Drago in the climactic match held in Moscow, the Russians are wooed by his mettle and grit, and before he knocks Drago out, they start chanting his name. Rocky IV culminates with a short motivational speech by the winner in which he implores everybody to get along, saying, ‘If I can change, and you can change – everybody can change.’ The film dispels the Cold War with blockheaded politics…but it dispels nonetheless.

While not as chiselled, oiled, and hyperreal as the benchmark Stallone/Schwarzenegger, Roddy Piper’s body-image stands out in They Live; lean, hard and donning a mullet hairdo reminiscent of Stallone-Rambo, he signifies the masculine spectacle and desire of the 1980s. Whether Carpenter intended it or not – although he probably did, given his penchant for satire and burlesque – Piper-Nada extrapolates Stallone/Schwarzenegger, parodying their roughneck personas and critiquing them as sites of power and agency. Consequently Piper-Nada is a simulacra, a copy of a copy – what Jean Baudrillard would call the ‘desert of the real itself’, cast in the mould of our mediatised and image-obsessed desires (1981: 1).4 This reference is apt: Baudrillard achieved cult status in the 1980s, theorizing postmodern consumer-culture and the eclipse of the self by the technocapitalist sign.5

Unlike Stallone/Schwarzenegger’s films – with the exception, perhaps, of the ontologically and metaphysically playful Total Recall (1990) – They Live puts heavy emphasis on the hyperreal nature of Piper-Nada and the world(s) that he inhabits. And unlike Rocky IV, They Live critiques Reaganism with extreme prejudice. This critique is important to the Baudrillardian arc of the film in that Reagan himself becomes yet another instance of hyperreality, as Mike Dubose suggests: ‘Reagan’s renegade/cowboy image effectively blurs the real political relationship between central authority, morality, and mainstream values not just for the president but for Reaganism in general’ (2007: 917).

BLOCKBUSTERS

Reagan’s hyperreal media-image operated in a similar way to the media-images of Stallone/Schwarzenegger: an instance of compensatory excess that placated male anxiety under the aegis of prospective doom. These cinematic bodies gestured towards a viable agency. With the blockbuster film, excess took the form of cinema itself, further reifying the social, cultural and economic abandon of the era. A representation par excellence of the excess that I have discussed up to this point, the blockbuster culls together pathologies and obsessions with body-image, capital and media technologies.

In the abstract, blockbuster films exhibit three Big features: production budgets, special effects and box office returns. In Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer (2004), a reference to Stanley Kubrick’s film Dr. Strangelove, or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964),6 Tom Shone writes:

Once a purely economic term, with no generic preference, it was conferred solely by a movie’s box office returns – and, by default, the audience. Thus The Sound of Music was a blockbuster [as was] Fiddler on the Roof and Kramer vs. Kramer. Today, it has – to paraphrase Julie Andrews – become the name a movie calls itself, before it is even out of the gate.…Now, it signifies a type of movie: not quite a genre, but almost; often science fiction but not necessarily; something to do with action movies although not always. (2004: 28)

Shone locates the origins of the multifaceted (if generically vague) blockbuster in the films of Steven Speilberg and George Lucas, namely Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977), although their work in the 1980s solidified the form. Previous critics denounce the filmmakers for dumbing down the movie industry.7 Shone focuses on the ways in which they innovated and revolutionised the industry. It’s impossible to deny the boyish appeal of such ‘high concept’ fare exemplified by ‘stylish and slick production qualities’ and ‘straightforward and easily categorized characters and familiar plots that could be described briefly’ (Thompson 2007: 97). This was a momentous shift from the auteur filmmaking of the 1970s – ‘scrappy, a little ragged, open-ended, ironic, ambiguous, often despairing’ (Prince 2007: 8) – even if the 1980s did not forsake auteurism altogether. But superficial glitz significantly displaced narrative depth. Guy Debord’s theory of the spectacle as ‘a social relationship between people that is mediated by images’ (1967: 12) powerfully resounds in the blockbuster.8 Blockbusters not only changed movies; they changed the way we think about movies (as representations) and our relationship to movies (as represented subjects)...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Dedication

- Introduction: The Becoming-Piper

- 1. The Cult of the Eighties

- 2. Wake-Up Call

- 3. Reel Politik

- 4. Through a Pair of Cheap Sunglasses Darkly

- 5. The Pathological Unconscious

- 6. Legacies

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access They Live by D. Harlan Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.