![]()

Time

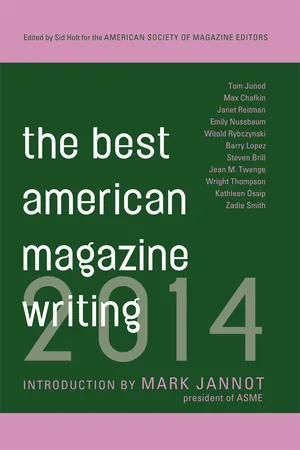

WINNER—PUBLIC INTEREST

There was little surprise this year when Time won the National Magazine Award for Public Interest for Steven Brill’s “Bitter Pill,” a 24,000-word piece that clearly explains the inordinately complicated business that is American health care. The reporting is thorough, even obsessive; the analysis, both dispassionate and damning; the sympathy for health-care consumers suffering financial distress, strongly felt yet never disabling. Brill was the founder of American Lawyer—which won four National Magazine Awards while he was editor in chief—and later CourtTV and Journalism Online, a company that helps publications charge for content. Time won the National Magazine Awards for Public Interest in 1999 and 2001, when Walter Isaacson was editor, and Magazine of the Year in 2012, while Rick Stengel was in charge.

Steven Brill

Bitter Pill: Why Medical Bills Are Killing Us

1. Routine Care, Unforgettable Bills

When Sean Recchi, a forty-two-year-old from Lancaster, Ohio, was told last March that he had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, his wife Stephanie knew she had to get him to MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Stephanie’s father had been treated there ten years earlier, and she and her family credited the doctors and nurses at MD Anderson with extending his life by at least eight years.

Because Stephanie and her husband had recently started their own small technology business, they were unable to buy comprehensive health insurance. For $469 a month, or about 20 percent of their income, they had been able to get only a policy that covered just $2,000 per day of any hospital costs. “We don’t take that kind of discount insurance,” said the woman at MD Anderson when Stephanie called to make an appointment for Sean.

Stephanie was then told by a billing clerk that the estimated cost of Sean’s visit—just to be examined for six days so a treatment plan could be devised—would be $48,900, due in advance. Stephanie got her mother to write her a check. “You do anything you can in a situation like that,” she says. The Recchis flew to Houston, leaving Stephanie’s mother to care for their two teenage children.

About a week later, Stephanie had to ask her mother for $35,000 more so Sean could begin the treatment the doctors had decided was urgent. His condition had worsened rapidly since he had arrived in Houston. He was “sweating and shaking with chills and pains,” Stephanie recalls. “He had a large mass in his chest that was … growing. He was panicked.”

Nonetheless, Sean was held for about ninety minutes in a reception area, she says, because the hospital could not confirm that the check had cleared. Sean was allowed to see the doctor only after he advanced MD Anderson $7,500 from his credit card. The hospital says there was nothing unusual about how Sean was kept waiting. According to MD Anderson communications manager Julie Penne, “Asking for advance payment for services is a common, if unfortunate, situation that confronts hospitals all over the United States.”

The total cost, in advance, for Sean to get his treatment plan and initial doses of chemotherapy was $83,900.

Why?

The first of the 344 lines printed out across eight pages of his hospital bill—filled with indecipherable numerical codes and acronyms—seemed innocuous. But it set the tone for all that followed. It read, “1 ACETAMINOPHE TABS 325 MG.” The charge was only $1.50, but it was for a generic version of a Tylenol pill. You can buy a hundred of them on Amazon for $1.49 even without a hospital’s purchasing power.

Dozens of midpriced items were embedded with similarly aggressive markups, like $283.00 for a “CHEST, PA AND LAT 71020.” That’s a simple chest X-ray, for which MD Anderson is routinely paid $20.44 when it treats a patient on Medicare, the government health-care program for the elderly.

Every time a nurse drew blood, a “ROUTINE VENIPUNCTURE” charge of $36.00 appeared, accompanied by charges of $23 to $78 for each of a dozen or more lab analyses performed on the blood sample. In all, the charges for blood and other lab tests done on Recchi amounted to more than $15,000. Had Recchi been old enough for Medicare, MD Anderson would have been paid a few hundred dollars for all those tests. By law, Medicare’s payments approximate a hospital’s cost of providing a service, including overhead, equipment, and salaries.

On the second page of the bill, the markups got bolder. Recchi was charged $13,702 for “1 RITUXIMAB INJ 660 MG.” That’s an injection of 660 mg of a cancer wonder drug called Rituxan. The average price paid by all hospitals for this dose is about $4,000, but MD Anderson probably gets a volume discount that would make its cost $3,000 to $3,500. That means the nonprofit cancer center’s paid-in-advance markup on Recchi’s lifesaving shot would be about 400 percent.

When I asked MD Anderson to comment on the charges on Recchi’s bill, the cancer center released a written statement that said in part, “The issues related to health care finance are complex for patients, health care providers, payers and government entities alike. … MD Anderson’s clinical billing and collection practices are similar to those of other major hospitals and academic medical centers.”

The hospital’s hard-nosed approach pays off. Although it is officially a nonprofit unit of the University of Texas, MD Anderson has revenue that exceeds the cost of the world-class care it provides by so much that its operating profit for the fiscal year 2010, the most recent annual report it filed with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, was $531 million. That’s a profit margin of 26 percent on revenue of $2.05 billion, an astounding result for such a service-intensive enterprise.1

The president of MD Anderson is paid like someone running a prosperous business. Ronald DePinho’s total compensation last year was $1,845,000. That does not count outside earnings derived from a much publicized waiver he received from the university that, according to the Houston Chronicle, allows him to maintain unspecified “financial ties with his three principal pharmaceutical companies.”

DePinho’s salary is nearly two and a half times the $750,000 paid to Francisco Cigarroa, the chancellor of entire University of Texas system, of which MD Anderson is a part. This pay structure is emblematic of American medical economics and is reflected on campuses across the United States, where the president of a hospital or hospital system associated with a university—whether it’s Texas, Stanford, Duke, or Yale—is invariably paid much more than the person in charge of the university.

I got the idea for this article when I was visiting Rice University last year. As I was leaving the campus, which is just outside the central business district of Houston, I noticed a group of glass skyscrapers about a mile away lighting up the evening sky. The scene looked like Dubai. I was looking at the Texas Medical Center, a nearly 1,300-acre, 280-building complex of hospitals and related medical facilities, of which MD Anderson is the lead brand name. Medicine had obviously become a huge business. In fact, of Houston’s top ten employers, five are hospitals, including MD Anderson with 19,000 employees; three, led by ExxonMobil with 14,000 employees, are energy companies. How did that happen, I wondered. Where’s all that money coming from? And where is it going? I have spent the past seven months trying to find out by analyzing a variety of bills from hospitals like MD Anderson, doctors, drug companies, and every other player in the American health-care ecosystem.

When you look behind the bills that Sean Recchi and other patients receive, you see nothing rational—no rhyme or reason—about the costs they faced in a marketplace they enter through no choice of their own. The only constant is the sticker shock for the patients who are asked to pay.

Yet those who work in the health-care industry and those who argue over health-care policy seem inured to the shock. When we debate health-care policy, we seem to jump right to the issue of who should pay the bills, blowing past what should be the first question: Why exactly are the bills so high?

What are the reasons, good or bad, that cancer means a half-million- or million-dollar tab? Why should a trip to the emergency room for chest pains that turn out to be indigestion bring a bill that can exceed the cost of a semester of college? What makes a single dose of even the most wonderful wonder drug cost thousands of dollars? Why does simple lab work done during a few days in a hospital cost more than a car? And what is so different about the medical ecosystem that causes technology advances to drive bills up instead of down?

Recchi’s bill and six others examined line by line for this article offer a close-up window into what happens when powerless buyers—whether they are people like Recchi or big health-insurance companies—meet sellers in what is the ultimate seller’s market.

The result is a uniquely American gold rush for those who provide everything from wonder drugs to canes to high-tech implants to CT scans to hospital bill-coding and collection services. In hundreds of small and midsize cities across the country—from Stamford, Conn., to Marlton, N.J., to Oklahoma City—the American health-care market has transformed tax-exempt “nonprofit” hospitals into the towns’ most profitable businesses and largest employers, often presided over by the regions’ most richly compensated executives. And in our largest cities, the system offers lavish paychecks even to midlevel hospital managers, like the fourteen administrators at New York City’s Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center who are paid over $500,000 a year, including six who make over $1 million.

Taken as a whole, these powerful institutions and the bills they churn out dominate the nation’s economy and put demands on taxpayers to a degree unequaled anywhere else on earth. In the United States, people spend almost 20 percent of the gross domestic product on health care, compared with about half that in most developed countries. Yet in every measurable way, the results our health-care system produces are no better and oft en worse than the outcomes in those countries.

According to one of a series of exhaustive studies done by the McKinsey & Co. consulting firm, we spend more on health care than the next ten biggest spenders combined: Japan, Germany, France, China, the U.K., Italy, Canada, Brazil, Spain, and Australia. We may be shocked at the $60 billion price tag for cleaning up after Hurricane Sandy. We spent almost that much last week on health care. We spend more every year on artificial knees and hips than what Hollywood collects at the box office. We spend two or three times that much on durable medical devices like canes and wheelchairs, in part because a heavily lobbied Congress forces Medicare to pay 25 percent to 75 percent more for this equipment than it would cost at Walmart.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that ten of the twenty occupations that will grow the fastest in the United States by 2020 are related to health care. America’s largest city may be commonly thought of as the world’s financial-services capital, but of New York’s eighteen largest private employers, eight are hospitals and four are banks. Employing all those people in the cause of curing the sick is, of course, not anything to be ashamed of. But the drag on our overall economy that comes with tax-payers, employers, and consumers spending so much more than is spent in any other country for the same product is unsustainable. Health care is eating away at our economy and our treasury.

The health-care industry seems to have the will and the means to keep it that way. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the pharmaceutical and health-care-product industries, combined with organizations representing doctors, hospitals, nursing homes, health services, and HMOs, have spent $5.36 billion since 1998 on lobbying in Washington. That dwarfs the $1.53 billion spent by the defense and aerospace industries and the $1.3 billion spent by oil and gas interests over the same period. That’s right: the health-care-industrial complex spends more than three times what the military-industrial complex spends in Washington.

When you crunch data compiled by McKinsey and other researchers, the big picture looks like this: We’re likely to spend $2.8 trillion this year on health care. That $2.8 trillion is likely to be $750 billion, or 27 percent, more than we would spend if we spent the same per capita as other developed countries, even after adjusting for the relatively high per capita income in the United States vs. those other countries. Of the total $2.8 trillion that will be spent on health care, about $800 billion will be paid by the federal government through the Medicare insurance program for the disabled and those sixty-five and older and the Medicaid program, which provides care for the poor. That $800 billion, which keeps rising far faster than inflation and the gross domestic product, is what’s driving the federal deficit. The other $2 trillion will be paid mostly by private health-insurance companies and individuals who have no insurance or who will pay some portion of the bills covered by their insurance. This is what’s increasingly burdening businesses that pay for their employees’ health insurance and forcing individuals to pay so much in out-of-pocket expenses.

Breaking these trillions down into real bills going to real patients cuts through the ideological debate over health-care policy. By dissecting the bills that people like Sean Recchi face, we can see exactly how and why we are overspending, where the money is going, and how to get it back. We just have to follow the money.

The $21,000 Heartburn Bill

One night last summer at her home near Stamford, Conn., a sixty-four-year-old former sales clerk whom I’ll call Janice S. felt chest pains. She was taken four miles by ambulance to the emergency room at Stamford Hospital, officially a nonprofit institution. After about three hours of tests and some brief encounters with a doctor, she was told she had indigestion and sent home. That was the good news.

The bad news was the bill: $995 for the ambulance ride, $3,000 for the doctors and $17,000 for the hospital—in sum, $21,000 for a false alarm.

Out of work for a year, Janice S. had no insurance. Among the hospital’s charges were three “TROPONIN I” tests for $199.50 each. According to a National Institutes of Health website, a troponin test “measures the levels of certain proteins in the blood” whose release from the heart is a strong indicator of a heart attack. Some labs like to have the test done at intervals, so the fact that Janice S. got three of them is not necessarily an issue. The price is the problem. Stamford Hospital spokesman Scott Orstad told me that the $199.50 figure for the troponin test was taken from what he called the hospital’s chargemaster. The chargemaster, I learned, is every hospital’s internal price list. Decades ago it was a document the size of a phone book; now it’s a massive computer file, thousands of items long, maintained by every hospital.

Stamford Hospital’s chargemaster assigns prices to everything, including Janice S.’s blood tests. It would seem to be an important document. However, I quickly found that although every hospital has a chargemaster, officials treat it as if it were an eccentric uncle living in the attic. Whenever I asked, they deflected all conversation away from it. They even argued that it is irrelevant. I soon found that they have good reason to hope that outsiders pay no attention to the chargemaster or the process that produces it. For there seems to be no process, no rationale, behind the core document that is the basis for hundreds of billions of dollars in health-care bills.

Because she was sixty-four, not sixty-five, Janice S. was not on Medicare. But seeing what Medicare would have paid Stamford Hospital for the troponin test if she had been a year older shines a bright light on the role the chargemaster plays in our national medical crisis—and helps us understand the illegitimacy of that $199.50 charge. That’s because Medicare collects troves of data on what every type of treatment, test, and other service costs hospitals to deliver. Medicare takes seriously the notion that nonprofit hospitals should be paid for all their costs but actually be nonprofit after their calculation. Thus, under the law, Medicare is supposed to reimburse hospitals for any given service, factoring in not only direct costs but also allocated expenses such as overhead, capital expenses, executive salaries, insurance, differences in regional costs of living, and even the education of medical students.

It turns out that Medicare would have paid Stamford $13.94 for each troponin test rather than the $199.50 Janice S. was charged.

Janice S. was also charged $157.61 for a CBC—the complete blood count that those of us who are ER aficionados remember George Clooney ordering several times a night. Medicare pays $11.02 for a CBC in Connecticut. Hospital finance people argue vehemently that Medicare doesn’t pay enough and that they lose as much as 10 on an average Medicare patient. But even if the Medicare price should be, say, 10 percent higher, it’s a long way from $11.02 plus 10 percent to $157.61. Yes, every hospital administrator grouses about Medicare’s payment rates—rates that are supervised by a Congress that is heavily lobbied by the American Hospital Association, which spent $1,859,041 on lobbyists in 2012. But an annual expense report that Stamford Hospital is required to file with the federal Department of Health and Human Services offers evidence that Medicare’s rates for the services Janice S. received are on the mark. According to the hospital’s latest filing (covering 2010), its total expenses for laboratory work (like Janice S.’s blood tests) in...