![]()

1

FOOTHOLD

IN THE HUMAN SEA OF SHANGHAI, a home is above all a foothold in the city, a sliver of territory one might claim for oneself and one’s family. Over the past century, the ownership of such territories did not remain static but rather underwent many historical vicissitudes. Mapping out the spaces of two houses and their associated alleyways, this chapter accounts for the changes in their inhabitants, boundaries, and usage from the Republican era through the Maoist and reform eras. Originally commissioned and owned by foreign investors, these homes had hybrid architectural styles that testify to Shanghai’s unique history of colonial capitalism, industrialization, and cosmopolitanism. As their foreign owners and inhabitants were repatriated with the end of World War II and the Communist Revolution, these housing compounds came under state possession and became collective property subject to redistribution through successive political campaigns. The former bourgeoisie and the rising class of proletariats became neighbors who observed the tumbling of each other’s destinies and a constant reshuffling of the social and political order.

Instead of being passive recipients of state welfare or tyranny, my grandparents and their neighbors enthusiastically flocked to the support of the new socialist regime in 1949, celebrating its success, participating in its construction, and joining its mass movements and surveillance systems. Their private interests found public manifestations, for they either really identified their personal welfare with that of the collective or made clever uses of state policies or political campaigns for their own ends. Sometimes the former activists’ enthusiasm backfired, and they would become the targets rather than the makers of revolution, which every now and then swept various waves of Shanghai residents off their feet into the hinterlands.

Most of those banished from Shanghai in the Cultural Revolution returned to the city in the early reform era, whereas other alleyway children who stayed in Shanghai grew into adults, formed families of their own, and competed with their parents and siblings for housing. From the late 1970s through the late 1980s, even once respectable alleyways decayed into slums with all their crooked and precarious illegal structures, which the residents themselves built with materials and labor scraped together from every relation. They also partitioned the interiors of existing structures into many dark corners to accommodate multiple generations—a volatile, reluctant coexistence that lacerated familial bonds and quickened the demise of alleyway homes.

Foundations and Original Residents, 1910s–1940s

Built in 1915 and 1927, respectively, the two alleyway homes in this study hold memories older than most of their living former residents. Despite external patching and internal remodeling over the past century, their architectural forms remained artifacts and relics of the early Republican era. Both lay in Shanghai’s northeast industrial zone known as Yangshupu (see fig. 0.3), originally a sandy shore until its industrialization and urbanization in the early twentieth century. Running parallel with the Huangpu River north of Suzhou Creek, Yangshupu Road, or Poplar Tree Shore Road, had China’s first tap-water factory and biggest electrical power plant by the 1880s, illuminating half of the city. After Japan’s triumph in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) gave foreign industrialists the legal rights to manufacture in Shanghai, the early twentieth century saw the flourishing of factories in this district, especially in the tobacco and textile industries. Despite disruptions by the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), big mills grew with small alleyway workshops, attracting hundreds of thousands of migrants from the countryside,1 among them my maternal grandparents and many of their later neighbors.

Whereas many migrant workers built transient bungalow-type, single-story houses and straw shacks for themselves,2 real estate investors built large-scale alleyway compounds for factory management or for rent to an emerging “middle class” of small workshop owners and foremen (or forewomen), often called Number Ones. Still, the residents of Yangshupu remained acutely aware of their marginal relation to the metropolitan center. As Grandma Apricot, who lived in one of these alleyways from 1938 to 2005, explained to me:

In my childhood, the Yangshupu area was still something of a frontier, with cotton fields and rice paddies alongside factory smokestacks, loading docks, and hutments built up by workers from the countryside. Our neighborhood thus belonged to what Shanghainese called the “lower corner” [xiazhijiao 下之角]. By contrast, the “upper corner” [shangzhijiao 上之角] in the city center was much more prosperous and chic, with lots of department stores and big bosses living in garden villas. When we wanted to go shopping in the “upper corner,” we would say: “We are going to Shanghai”—we did not consider where we lived Shanghai.3

No. 111, Alliance Lane, 1927–1950

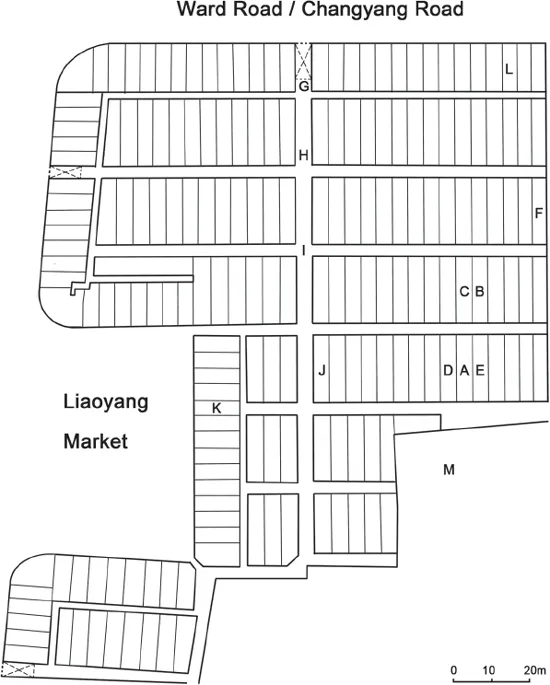

In 1927, a British real estate company, Metropolitan Ltd. (Hengye 恆業 in Chinese), invested in the construction of a large shikumen housing compound on Ward Road and named it Alliance Lane (Youbang Li 友邦里).4 This alleyway consisted of 141 units of single-bay houses (3.5-by-15 square meters) mapped densely onto a territory of about 12,700 square meters, with 15,500 square meters of building area (fig. 1.1).5 If we think of the compound’s internal structure as a tree that grew southward, the main entrance was at the “root,” through which one walked into the “trunk” of the main alleyway, with “branches” of small alleys on both sides, all dead ends except for two leading to a side street and two others connecting to neighboring alleyway compounds. The northern and eastern rows of houses had shops facing the street on their ground floors, following the dual structure of “outside shops and inside neighborhoods” (waipuneili 外鋪內里).6 The overall layout of the compound thus interwove commercial openness with residential privacy into an intimate labyrinth (figs. 1.1–1.4).

FIGURE 1.1 Layout of Alliance Lane. A: No. 111, the main house in this study (see fig. 1.5). B: No. 83, where Apricot lived after 1949. C: No. 81 (see Mother Mao’s story in “Several Lifetimes to a Life” in chapter 3). The ground floor of the row of houses that include B and C were converted into a kindergarten in 1958. D: No. 109 (see Mother Yang’s story in “Several Lifetimes to a Life” in chapter 3). E: No. 113 (see “Home Searches” in chapter 2). F: No. 61, which once hosted a Communist radio station. G: Alleyway entrance (see fig. 1.2). H: Position for the stage of struggle sessions during the Cultural Revolution. I: The vantage point from which one might view figs. 1.3 and 1.4. J: No. 91, site of the later neighborhood committee. K: An alleyway school. L: A photographer’s studio (see fig.1.2). M: A neighboring alleyway. Sketch by Yang Xu.

FIGURE 1.2 View of the main entrance of Alliance Lane from the street, with a photographer’s studio and a “tiger stove” that sold hot water and tea on the left, a paper and tobacco shop, and a barber shop on the right. At the alleyway entrance is a cobbler and a woman using a public telephone. Rather than a photographic representation, this drawing depicts my mother’s memory of the most typical everyday shops in her childhood. Drawing by my father, Li Bin, and mother, Wang Yaqing.

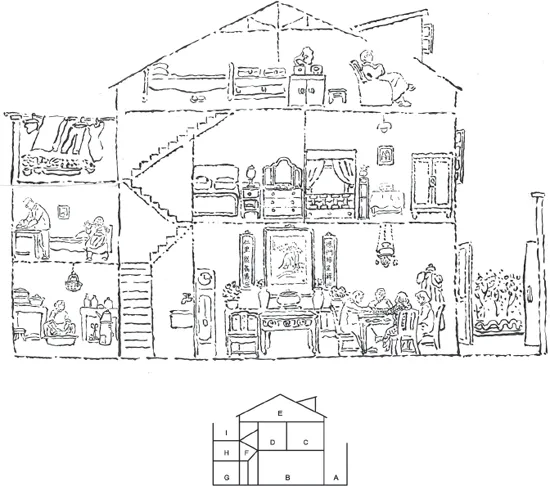

Built throughout Shanghai from the 1870s to the 1930s, shikumen alleyway homes were hybrid in their architectural planning. The individual houses had a traditional courtyard layout, south-facing orientation, and local decorative motifs. Yet whereas traditional Chinese alleys were natural accumulations of residences built as freestanding structures in different times and with varying styles, shikumen houses were rationally planned and uniformly constructed in high density to maximize the profit from the rent.7 Thus, shikumen housing became, as architectural historian Chunlan Zhao points out, “a perfect match to satisfy nostalgia for traditional Chinese living and the demand for modern urban dwelling with great concern for economy.”8 Consisting of two stories and an attic, each unit of Alliance Lane had a layout reminiscent of the traditional Chinese house and was designed to accommodate a single multigenerational family (fig. 1.5). When entering the stone portal gate on the unit’s south, “frontal” side, one first crossed a courtyardlike sky well (tianjing 天井, 6 square meters) into the living room, or guest and ancestral hall (ketang jian 客堂間, 24 square meters). At the back of the guest and ancestral hall was a door that opened onto the staircase, beyond which was the kitchen (8 square meters) and back door. Above the kitchen and halfway up the staircase was the tingzijian 亭子間, or pavilion room (8 square meters), and above that a sun terrace. The darker and smaller spaces of the kitchen and pavilion room faced north. Because the sun shone into the house from the south in the winter and from the north in the summer, these spaces were cold in the winter and hot in the summer. Along with the attic right beneath the roof, they were considered the back spaces for the family’s servants. By contrast, the brighter spaces of the guest and ancestral hall and the bedroom faced south and were thus warm in winter and cool in summer—they were thus considered the front spaces for the masters of the house. Such a hierarchical spatial arrangement would undergo radical transformations later when multiple families came to inhabit this house.

FIGURE 1.3 View of Alliance Lane’s big alleyway and entrance northward from the same vantage point as figure 1.1I. Refer to the section “Alleyway Space as a Milieu for Gossip” in chapter 3 for a more detailed explanation of the social life depicted in this image. Drawing by my parents.

FIGURE 1.4 View of an Alliance Lane alleyway branch eastward from the same vantage point as figure 1.1I. The big doors on the left are the stone portal gates, or shikumen, that gave this type of architecture its name. These are the “front doors,” whereas the small doors on the right side are the “back doors.” Drawing by my parents.

FIGURE 1.5 A cross-section view of an unmodified individual unit in Alliance Lane in the 1940s. This depiction is roughly based on Grandma Apricot’s description of her family in this chapter, with the difference that Apricot’s family had remodeled the third-floor attic into a proper third story. A: Sky well (tianjing 天井). B: Guest and ancestral hall (ketang jian 客堂間). C: Front bedroom (qianlou 前樓). D: Back bedroom (houlou 後樓). E: Third-floor attic (sanceng ge 三層閣) with a tiger window (laohu chuang 老虎窗). F: Staircase, next to which is a faucet room, which has no ceiling and is also called a “small sky well.” G: Kitchen (zao pijian 灶披間). H: Pavilion room (tingzijian 亭子間). I: Sun terrace (shaitai 曬台). Drawing by my parents.

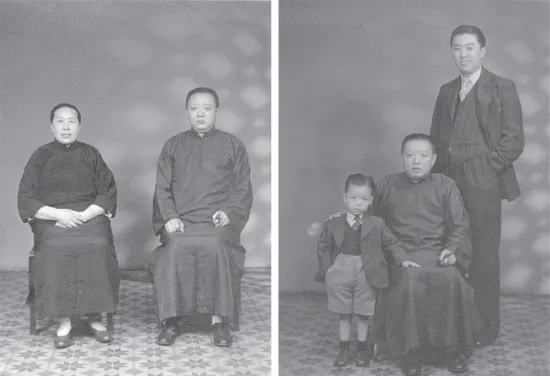

FIGURE 1.6 Residents of No. 111 Alliance Lane from the 1930s to the 1950s: Apricot’s grandparents, father, and younger brother around 1948. Photograph courtesy of Grandma Apricot.

FIGURE 1.7 Apricot (middle) and two neighbors in Alliance Lane around 1947. The girl to her right is Golden Precious of No. 109 (see “Several Lifetimes to a Life” in chapter 3). Photograph courtesy of Grandma Apricot.

From 1938 to 1952, three generations of the Wang family (fig. 1.6 and 1.16) lived in No. 111 Alliance Lane. The eldest Mr. Wang was a manager at the nearby British American Tobacco factory.9 He and his wife had only one son, a Number One at the same factory, who married a female worker under his supervision and had three children with her. Their eldest daughter, Apricot (fig. 1.7), married across the alleyway and continued living in Alliance Lane until its demolition in 2005. Over several afternoon chats in 2000, Grandma Apricot (fig. 1.8) recounted to me memories of her childhood home:10

When my grandfather first rented No. 111 from the British Hengye company, he had to pay a one-time takeover fee [dingfei 頂費] in the currency of three “big yellow fish,” gold bars weighing about 150 grams each.11 As a manager for British American Tobacco, my grandfather was in charge of buying coal, and coal mines sometimes bribed him to secure his business. I still remember how he poured out a huge sack of money onto our Eight Immortal Table one night for the entire family to count together. Since money was worth less with every passing day, however, my grandmother would exchange all this cash for gold bars. She then b...