![]()

1/THE MUSLIM COUNTRIES IN THE

MOVEMENT OF HISTORY

LEAVING ASIDE THE SOUND AND FURY OF MEDIA COVERAGE, we can define and follow the movement of history in a simple way. The progression of rates of literacy for the planet as a whole provides a vision, both empirical and Hegelian, of an irresistible ascension of the human spirit.1 Every country, one after the other, marches happily toward a state of universal literacy. This general movement does not match the image of a humanity divided into irreducible if not antagonistic cultures or civilizations. There are gaps, but there are no exceptions, especially no Muslim exception.

Census surveys that distinguish between age groups make it possible to determine the date at which, in any given society, half the men or women between the ages of 20 and 24 know how to read and write, a decisive moment of transformation when the first generation reaches adulthood with a majority of its members literate. The rate of increase accelerated in the twentieth century. One after the other, in all countries, 50 percent of men achieved literacy, followed after variable lengths of time by 50 percent of women.

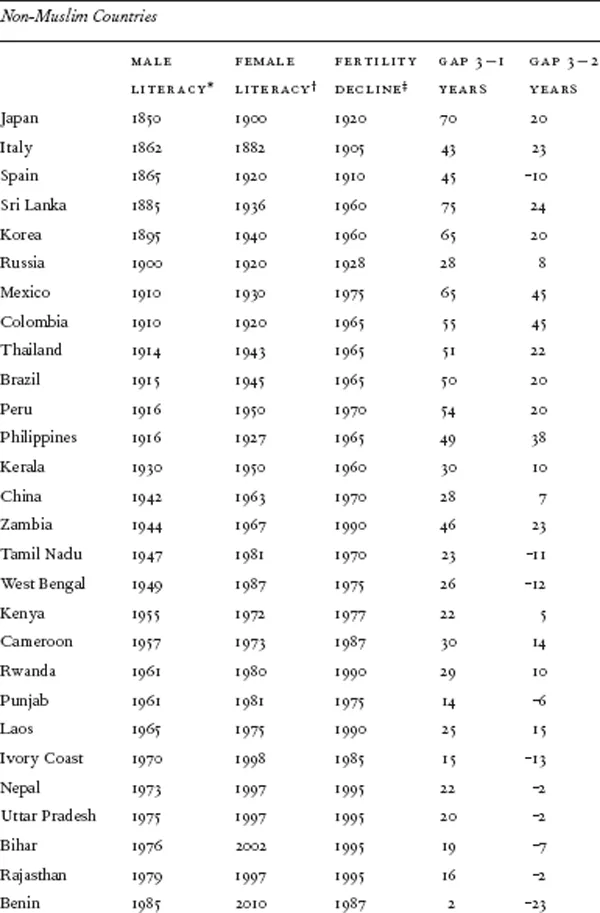

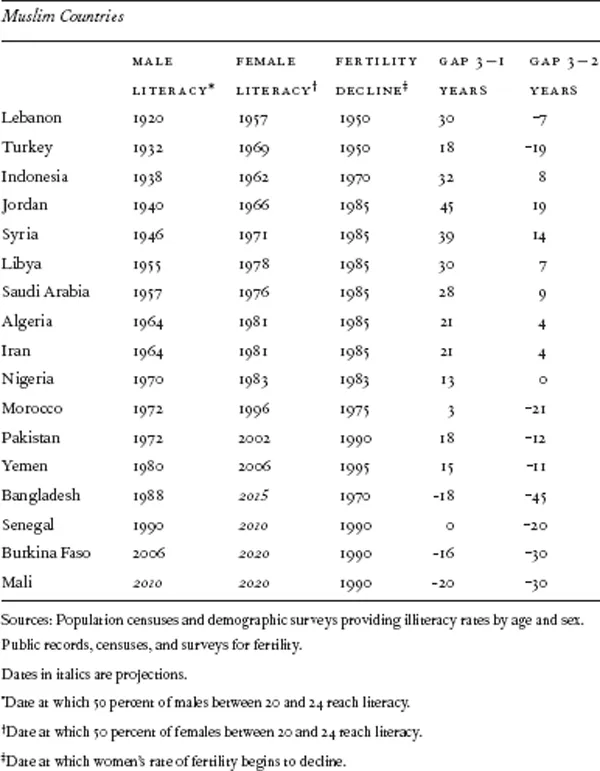

Muslim or majority Muslim countries (see table 1.1) were not in the front rank. But Turkey passed the level of 50 percent for male literacy around 1932. Jordan and Syria, in the heart of the Arab world, did so, respectively, around 1940 and 1946, coming on either side of China (1942). Women followed, with a little more delay in the case of Jordan (26 years) and Syria (25 years) than in that of China (21 years). On the scale of universal history, these differences are minimal, if not insignificant. The heart of the Arab world was indeed one or two centuries behind northern Europe, but only eight decades behind Mediterranean Europe, seven behind Japan, four behind Russia, and three behind Mexico. Its pace of cultural development was close to that of the most advanced large Indian states, such as West Bengal and Tamil Nadu, and also close to the most populous and most peripheral Muslim state, Indonesia. Malaysia, another representative of outlying Islam, was slightly behind the heart of the Arab world and behind neighboring Indonesia, because men did not pass the decisive threshold of 50 percent until around 1958. In the 1960s, Tunisia, Algeria, Iran, and Egypt reached their point of entry into the world of reading and writing. Morocco and Pakistan did not join them until around 1972. The least advanced portion of the Arab world, represented by Yemen, was close in its pace of educational development to the most backward part of northern India. The threshold was passed only around 1980, as compared to 1975 in Uttar Pradesh, 1976 in Bihar, and 1979 in Rajasthan. Bangladesh, Indian in language but Muslim in religion, did not reach it until around 1988.

If we set aside Indonesia, Malaysia, and Islamized black Africa—though this does represent 35 percent of the Muslim population—the major Muslim countries of the central zone are characterized by relatively low status for women, corresponding to a specific family structure, which will be described in chapter 3. And the overall level of literacy at any given moment is largely conditioned by the status of women. Where they are treated as minors, mothers do not have the authority to raise their children effectively, and the cultural dynamics of the society show the effects of that lack. But one can observe only a slowing, not a blocking effect. Moreover, the status of women explains just as much the backwardness of Confucian and Buddhist China as that of Muslim Jordan and Syria, and the backwardness of Hindu Uttar Pradesh as much as that of Muslim Pakistan and Yemen. In addition, if one considers the sample as a whole, one observes that the average gap between men and women in crossing the threshold is about 25 years for Muslim countries as for the others: This measure of the pace of the elimination of illiteracy does not show any particularity with regard to Islam.

Although family systems—more or less feminist—explain in part the gaps in rates of educational progress, the position in the area of any particular country, its location in reference to centers of global development, also plays a role. Literacy maps—global, regional, or local—always show diffusion through spatial contiguity. The exceptional backwardness of Morocco, Pakistan, Yemen, and Bangladesh is not solely an effect of the status of women: It also has to do with their outlying position in the Muslim world. Until a very recent period, one could explain in the same way the delay in the elimination of illiteracy in Brittany and Portugal, two very feminist if not matriarchal regions, but also outlying ones.

Whatever the context, development studies never omit literacy in the collection of variables supposed to describe the state of relative advancement of a country. But we are still living in the shadow of a dominant conception of history that persists in not seeing that economic liftoff is a consequence rather than a cause of the growth of literacy. Even accomplished historians allow themselves to be taken in, refusing to take into account the fundamental interactions between patterns of thought that are largely independent of economic processes. Living standards, the rate of growth of the gross domestic product, and unemployment can be attached to these interactions, but in a secondary way.

THE GROWTH OF LITERACY AND THE DECLINE IN FERTILITY

After the growth of literacy, the diffusion of birth control is a second fundamental element in the accession to a higher stage of consciousness and development. And once again, the Muslim world is entering universal history, at its pace and following its path, but toward a culminating point that is the same as that of everyone else.

Statistical analysis, combined with the feminist ideology of our time, has led to an emphasis on the primordial role of women. Minimizing their role in birth control would be as absurd as denying their role in the production of children. But refusing to take into account the role of men in diffusing contraception would also be a great absurdity, even though we must accept the modesty of their specifically sexual contribution to the process of human reproduction. Fathers work, sustain the family budget, and are concerned with the education and generally the future of their children. Their attitude toward birth control cannot fail to have significant effects.

The analysis of the correlation between variables at any given moment may mask the role of men. If one compares literacy levels and fertility rates at a recent date, when the elimination of male illiteracy had been completed, one notes that the lack of change in male literacy levels meant that they no longer had a visible statistical effect on fertility.

But if one adopts a dynamic view of the process of modernization, by linking the date of decline in fertility to the date of crossing a threshold of literacy of both men and women, men and women are placed in statistically equivalent positions. The analysis of correlations then sheds more light specifically on the progress of male literacy. Differences between male and female roles can then come to light, and either they are insignificant or they reveal male predominance in procreation decisions.

For the sample as a whole, including Muslim and non-Muslim countries (table 1.1), the correlation is +0.98 between levels of male and female literacy; +0.84 between the progress of male literacy and the decline in fertility; and 0.80 between the progress of female literacy and the decline in fertility. This is a set of very strong correlations.2 The gap between sexes is of little significance, but does indicate a slight advantage for men. But if one focuses on Muslim countries in the sample alone, the correlation between male literacy and decline in fertility falls to +0.61, a significant but not very strong value. The coefficient linking female literacy and decline in fertility falls to +0.55, a weak value.3 In Muslim countries, the role of male literacy, although weaker than elsewhere in the world, nevertheless seems more distinct than that of female literacy: A coefficient of 0.61 explains 37 percent of the variation. In Lebanon, Turkey, Malaysia, Iraq, Egypt, Tunisia, Morocco, Pakistan, and Yemen, fertility declined before women between 20 and 24 reached the 50 percent threshold of literacy, in countries where men had already crossed that threshold. We have already described this specific role of the increasing literacy of men in the Muslim demographic transition in the context of a study of Morocco.4

TABLE 1.1 Literacy and Fertility Decline in World History

There are also Muslim countries where a majority of both men and women had to attain literacy in order for fertility to decline. In Syria and Jordan, the time between the attainment of female literacy and the decline of fertility was even relatively long (14 and 19 years, respectively). In Algeria, Iran, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, and Mali, the decline followed swiftly after women crossed the literacy threshold.

A disconnection between female literacy and fertility decline can sometimes be observed outside the Muslim world. Late-eighteenth-century France is a very special case, but its importance cannot be minimized insofar as it invented birth control covering an entire society. But the case of Spain should also be noted. In the most recent phase of human history, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Bihar, Benin, and Ivory Coast have also followed this model. The acceleration of the demographic transition in these countries was no doubt the result of greatly increased pressure of the population on the means of survival. The decline in mortality that followed World War II brought about an increase in the population that was likely to lead to emergency measures for slowing its growth.

In a few extreme cases, the decline in fertility occurred not only before a majority of women between 20 and 24 achieved literacy, but also before a majority of men did so. In Bangladesh, an extreme case of demographic pressure in a hostile environment, fertility declined before 50 percent of men had attained literacy. These cases are rare and recent, and affect countries where rapid demographic growth has cast the population into a veritable Malthusian trap. But in general, male literacy seems to have been a minimum requirement: In 46 of the 49 countries, regions, or states in our sample, crossing the threshold of 50 percent male literacy preceded the decline in fertility.

Protestant northern Europe exhibited huge gaps, exceeding a century, between the elimination of male and female illiteracy and the decline in fertility. France, in contrast, led by the Paris Basin, seemed to need only the literacy of the men in the northern part of the country to adopt birth control. These extreme phenomena are linked to the pioneering role of the Continent in educational development and demographic modernization.

If we set aside France and the countries of northern Europe, and if we divide the countries in the sample into Muslim and non-Muslim countries—Catholic, Buddhist, Confucian, Hindu, or animist—we can observe in Islamic lands a shorter average time between the attainment of literacy and the decline in fertility.

In the varied subsample ranging from Mediterranean Europe to South America, Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa (28 countries, there is an average gap of 34 years between the date at which men cross the literacy threshold and the decline in fertility. The elimination of female illiteracy on average precedes by only 8 years the demographic shift. But we should never forget that female literacy presupposes and includes male literacy. This temporal telescoping with respect to women indicates primarily the complementarity of male and female roles. It is usually literate couples who decide on contraception together.

For the 21 countries of the Muslim sample, the time between male education and the diffusion of birth control is only 14 years. As for women, literacy of the majority comes on average 9 years after fertility begins to decline.

These gaps need to be explained. The determining power of the educational variable is not absolute: It has happened that fertility has not changed for more than a century after mass literacy was achieved, or that natural reproduction has immediately given way in the face of educational development (of men alone in certain recent extreme cases). Part of the shortening of the time between literacy and contraception in recent decades obviously has to do with the rapid increase of demographic pressure. On a planet whose population has increased from 2.5 to 6.7 billion between 1950 and 2007, a certain number of emergency reactions were to be anticipated in many regions. But there is also a variable involving patterns of thought that is ubiquitous and diverse, powerful but sometimes unpredictable, that helps to explain the time differences: the religious variable. An examination of the demographic history of the last two centuries, however, once again is disappointing for the socio-theologians of the clash of civilizations. Islam, unlike Protestantism and Catholicism, does not seem to be in a position to put up serious resistance to the decline in fertility.

A “DISENCHANTMENT”5 OF THE MUSLIM WORLD

The phenomenon of religion has an existence independent of the particularities of each set of beliefs. At a deep psychological and social level, Christianity, Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and animist religions are the same thing: an interpretation of the world that gives meaning to life and enables men to function properly in the societies into which they have been born. The detailed nature of belief, the kind of divinity, the type of metaphysical salvation foreseen, the moral code, and prohibited behavior can be examined only at a second stage of analysis. There is first of all the fact of believing anything at all beyond what is visible and demonstrable that is common to all religions. Also common to all religions is the social bond established by the shared belief. For the fundamental paradox of religion is that it is always simultaneously individual and collective: It defines a link between the individual and a metaphysical beyond, but an isolated individual is in general incapable of believing in any transcendence at all.

A society equipped with a stable and certain belief system provides its members with a meaning for things and for life. In such a context, reproduction may seem to be natural and necessary. The religions that have survived among large populations by definition transmit a positive vision of procreation: Those that, in contrast, have asserted the meaninglessness of procreation—and they have existed—have been doomed to die out with their adherents. For major religions, whether or not they are universalist, children who come into the world have meaning, as the world itself does. They therefore naturally have a natalist view, although it may be qualified. Christianity manifests a negative attitude toward sexuality, which has sometimes led it to favor celibacy, whose effects are obviously antinatalist. Islam is more tolerant of pleasure and of certain forms of contraception, the practice of which may indeed reduce the birth rate. Azl, or coitus interruptus, was accepted by Muhammad and, by extension, Islam tolerates all other forms of contraception. But beyond these nuances, the general attitude of all major religions is to encourage reproduction as the application of a divine plan. If God created man, it was not so that he would disappear, but would multiply. These obvious points need to be reiterated before examining what happens when religious belief collapses.

The simplest thing is to proceed historically and empirically by describing the first declines in fertility, which occurred in the context of the European cultural and economic liftoff, beginning in the late eighteenth century. The pioneering country was France, where fertility began to decline in the small towns of the Paris Basin in the twenty years preceding the Revolution. The process was generalized apparently in connection with the political transformation. The total fertility rate fell from 5.5 in the mid-eighteenth century to 4 children per woman around 1830, 3 around 1890, and 2.5 around 1910. On the eve of the Revolution, the Paris Basin belonged in its level of development to northern Europe, but it was far from the most educationally advanced region. Half of young men knew how to read and write, but the proportion of the population that was literate was much higher in Protestant countries such as England, Sweden, Holland, and Prussia. Even Catholic Germany was more culturally advanced. The classic correlation between female literacy and decline in fertility would suggest that fertility decline should have occurred first in northern Europe, which was a pioneer in education. What factor can explain France’s precocity? Quite simply, the collapse of religious belief that took place over the half century preceding the Revolution. Beginning in the 1730s and 1740s, the recruitment of priests dried up in the Paris Basin. In northern Europe, Protestant or not, religious belief resisted, as did fertility, for an entire century, despite a distinctly higher educational level.

Religious recruitment and observance started to flag in England and the Netherlands after 1880, and in Sweden and Prussia after 1890. Simultaneously, or with a few years’ delay, fertility fell off and Protestant nations began the demographic transition.6

Between 1921 and 1930, the fertility rate in England was 2.16; in Germany, 2.20; in Sweden, 2.24; and in France, 2.30. The coincidence between religious collapse and the spread of birth control is striking and unquestionable. It should not be forgotten that crossing a certain threshold of literacy was a necessary condition. In regions such as Andalusia or southern Italy, where religious observance collapsed, as in France, in the second half of the eighteenth century, but where the population remained largely illiterate, fertility did not decline. What the demographic history of Europe reveals is the existence of a twofold determination leading to birth control, two equally necessary conditions: the rise in educational level and the decline in religious observance, two phenomena that were obviously linked but not in a simple or instantaneous way.

A third phase of decisive decline in fertility can be observed in the wake of the postwar baby boom. Although one cannot consider the ebbing of religious observance to be the primary factor producing Europe’s currently very low fertility rates, a partial coincidence should once again be noted. Beginning in 1965, Catholic religious observance collapsed where it had remained significant: on the periphery of France, in southern Germany and the Rhineland, in the southern Netherlands and Belgium, in northern Italy, northwestern Spain, northern Portugal, and Quebec. The latest decline in fertility in the Western world occurred in the immediate aftermath of the last religious decline.

Western Europe, Catholic and Protestant, was not the only place where the law making the collapse of religious belief a prerequisite for the decline in fertility applied. In Russia and China, the ebbing of religion seemed to be an immediate consequence of a communist ...