![]()

PART I

Value

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Problem with Price? It’s Not Value

What is a cynic? A man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.

OSCAR WILDE, “LADY WINDERMERE’S FAN,” 1892

ON MAY 6, 2010, the shares of technology services consulting firm Accenture crashed from $40 to $0.01 in three minutes, wiping out 99.99 percent of its $35 billion market capitalization. Simultaneously, other companies’ share prices gyrated wildly. The combined impacts reflected a $1 trillion loss, measured in share prices, or 9 percent of the index value. Minutes later, the share prices had mostly recovered.

This speedy decline and subsequent bounce back was called the “flash crash.” Although this flash crash was notable for its size, miniature flash crashes of 5 to 30 percent, with subsecond price recoveries, occur surprisingly frequently. And during more common single-share flash crashes, prices can decline 30, 50, 80, and even 99 percent in seconds, only to recover moments later. Similar booms in price can also occur. The day of the 2010 flash crash saw Apple’s shares trading briefly for up to $100,000/share, making Apple’s market capitalization a robust $93.2 trillion—greater than the combined gross national product of all the countries in the world.

Nothing shows the folly of price better than these recurring flash crashes. There was no major change in the intrinsic economic value of Apple or Accenture on May 6, 2010. The crazy prices were the result of algorithms that didn’t know a thing about the true value of the underlying companies. For all the algorithms cared, they could have been trading the price of dung balls in New Delhi. The algorithms were focused not on the value of the underlying companies, but on exploiting and harvesting statistical price anomalies, reacting in a matter of microseconds.1 When algorithms working at that speed start to feed on each other, crazy things can happen. If you own a great company like Coke and algorithms start trading it at $0.02/share, although it traded at $40/share moments before, the distinction between intrinsic corporate value and price is pretty easy to spot.

The flawed prices created during flash crashes showcase a computer-driven, time-compressed version of a flawed price-making process that goes on all the time, namely, a process in which prices are set by two parties, neither of whom understands the long-term economic value of the underlying asset they trade. When a stock price declines, it means that for a given moment most human or algorithmic traders believe a firm’s value has lessened. This doesn’t mean a firm’s value has changed at all, it’s just a belief expressed as a number. Day to day, however, most people forget this and instead equate price with economic value. But price is a mere reflection of true value, like Plato’s shadows on the cave wall.

In flash crashes, mispricing only lasts for a few moments. But in many cases, mispricing can last for months, or even longer. The tech bubble of the late 1990s, for instance, lasted for years. On the other hand, bargains—like Costco during its early years—may sit quietly, underappreciated for years before gaining momentum to reflect their true value.

Many asset valuation estimates rely on models that use only historical prices or other flawed inputs. Applying price-based models to assets can lead to large losses. Flawed and poorly applied price models were used to structure and price mortgage bundles in the 2000s. These bad price models contributed to the $6.7 trillion U.S. real estate bubble and the subsequent losses associated with the U.S. housing crisis of 2007. Common sense about value and risk was replaced with a statistical pied piper called a Gaussian cupola model, which, along with other problematic models, was then used to rate and evaluate the value of securitized mortgages. Behind many financial crises is a large group of people creating credit based on bad models or other false beliefs confusing upward price momentum with value creation. With so much misunderstanding of the relationship between price and value, the allocator who truly understands a firm’s value will find herself at a significant advantage.

The Misunderstanding of Price

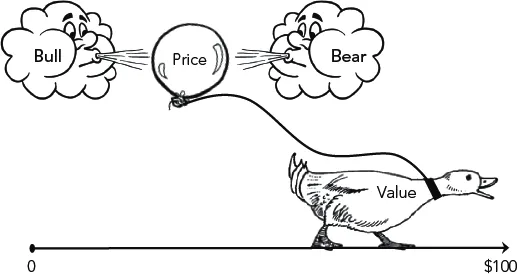

The line of thinking that equates prices with value naïvely assumes that everything is worth its current price. Imagine, for instance, you have a goose who lays golden eggs. Outwardly, it looks just like a normal goose. If you asked people how much they would be willing to pay for the goose, and they did not realize the secret of the golden eggs, the answer would not reflect its true value. People would instead price it just like any other goose.

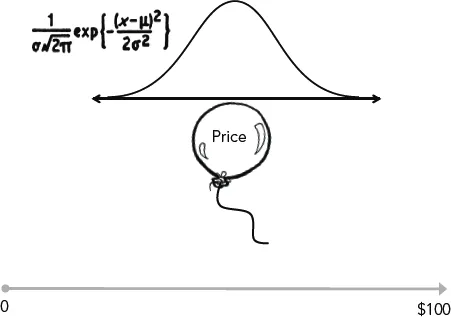

This is illustrated in figure 1.1. Price is pictured as a balloon hovering over the goose, connected to it by a stretchy string. As the goose’s intrinsic value wanders slowly forward (increasing) or backward (decreasing)—depending, let’s say, on the changing number of golden eggs it’s able to produce—the price balloon gets bounced to and fro by gusts of hot air and opinions expressed as traded prices. The winds of opinion push the balloon in front of (trading at a premium to) or behind (trading at a discount to) the intrinsic economic value of the goose.

FIGURE 1.1 The Goose and the Balloon

Price is created by opinions of value.

These daily opinions and price changes don’t change the nature of the goose’s value; thus a company’s intrinsic value, like the value of the golden goose, is often different from its price. The farther price gets away from value, the more likely it is to snap back. When the price balloon is far behind value, there may be a bargain in buying before price eventually moves forward to catch up with value. At other times, the price balloon is blown too far in front of the goose by excited traders. Most people obsess about the active and highly visible price balloon. In the long run, however, price activity doesn’t matter; the goose—value—takes price to where it belongs. A goal of this book is to shift the reader’s thinking from price to a deep understanding of value. I call this the “nature of value” perspective.

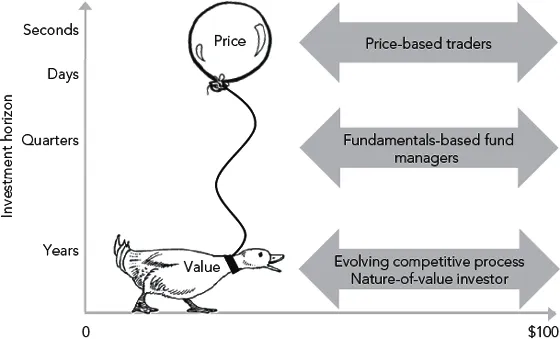

As shown in figure 1.2, different groups rely on price in different ways and to different degrees. Investment decisions are made based on price expectations, and are greatly influenced by an investor’s time horizon. In short-term time horizons, price reflects opinions of value, but as time horizons stretch out, price tends to more realistically represent the competitive nature and value of the firm’s earnings and assets. Famed value investor Benjamin Graham correctly stated that in the short term, the stock market acts like a voting machine, and over the long term, it acts like a value-weighing machine.

FIGURE 1.2 Time Horizons and Decision Factors Used by Various Investor Types

Individuals from various schools of thought apply many methods to rationalize the price–value relationship. The trader’s approach to price attempts to identify patterns in historical price shifts, focusing on past price rather than a company’s actual value. Efficient market theory posits that price is value, and that price correctly reflects all possible known information about value at all times. Traditional behavioral economic models understand price as being based primarily on past price beliefs. Some analysts use comparative metrics of comparable firms and yields to justify prices. Each of these approaches has limitations, and each fails to grasp the importance of expected value in the firm’s changing, competitive context. Let’s delve a little deeper into these approaches to price and value, and the possible economic dangers they pose, in order to see how the nature of value perspective differs from and may improve on each one.

Traders: The Entropy Enablers

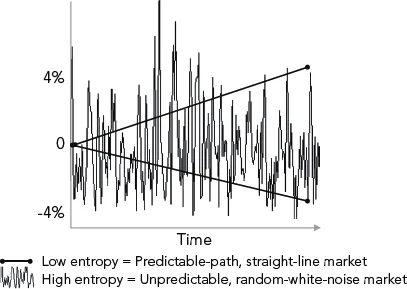

Most trading activity has little to do with an understanding of value. Traders add liquidity and greater statistical noise into price returns, as measured over time. Another way to say this is that traders introduce more entropy into the system.2 Entropy is a measure of statistical complexity. Short-term traders use statistical tools or intuition to identify patterns, trending behaviors, and mean reversion from the seemingly random historical noise of price. Each time a trader repeatedly exploits a price pattern, he or she introduces entropy into the short-term price.

A simple price pattern might be that for 20 weeks in a row shares in IBM went up on Tuesday. A person seeking to take advantage of this might start buying on the next Tuesday morning at the open and selling before the Tuesday close. As more people pursue the strategy, entering earlier and exiting earlier, the “predictable” low entropy pattern—or arbitrage opportunity—disappears. Arbitrage typically refers to taking advantage of a price difference between two markets, but arbitrage in the statistical sense involves taking advantage of simple price patterns to such a degree that only highly complex or seemingly random non-exploitable price patterns remain. As the earlier pattern disappears, the price time series appears more random as it gets more statistically complicated. At some point, entropy increases to a level at which easily exploitable patterns disappear in a cloud of white statistical price noise. This process is illustrated in figure 1.3.

Short-term trading has a legitimate economic value in providing liquidity, but trading’s economic contribution is overhyped when considered as the mechanism for performing value discovery and economic signaling. A firm’s economic or intrinsic value rarely changes in microseconds or minutes—but algorithms and opinions do. So although active trading produces some useful liquidity, most of it just produces statistical noise. Traders make money by identifying low entropy patterns and end up creating high entropy price patterns as residue. As we shall see later on, processes like this that consume low entropy and create high entropy are universal.3

FIGURE 1.3 Traders Increase Price Entropy

Traders consume predictable low entropy patterns, arbitraging them away and creating increased unpredictable price entropy.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis

Because of the “noisiness” of price—caused in part by traders exploiting simple patterns, as described above—a price’s next bounce can’t be predicted. In short time horizons, academics will tell you that price’s movements approximate the Black-Scholes equation, derived from a method originally created by physicists to model heat diffusion, and shown in figure 1.4. In its total focus on price, Black-Scholes ignores the goose entirely. Although models like this may be accurate in the short term, the approximation becomes dangerously irrelevant as time horizons lengthen. Many financial problems have resulted from misapplying the Black-Scholes approximation of price over longer time horizons.

FIGURE 1.4 The Black-Scholes Model Ignores the Goose

Short-term price balloon movements approximate a heat diffusion process. Black-Scholes–based finance and risk models ignore the goose entirely.

The dominant academic economic model is the efficient market hypothesis, which basically states that price always reflects all available information about value at a given time.4 For believers of versions of efficient market theory, ...