![]()

PART I

The Theory and Practice of Active Coping

![]()

1

The Power of Active Coping

THE CORPORATE WORLD IS a highly charged, ever-changing crucible. Leaders in it are sorely tested. There are other arenas just as tough—the military and politics, to give two examples. In the wake of the 2008 economic meltdown, many of us have been asking the same questions that I have been exploring for years. Is it possible to predict which executives are potential time bombs, to learn to tell a young Warren Buffett from a young, merely competent investment banker? And is it possible to help executives understand how some aspects of their personalities could adversely affect performance at work or which an awareness of might help them modify their behavior? I believe that it is possible to make such predictions with a fair degree of accuracy, and this book discusses how I have tried to do that.

An effective leader must meet challenges and resolve them productively, day after day. He or she must constantly adapt to the unforeseen—and must mobilize, coordinate, and direct others. But when hiring executives, how do you know which candidates possess such qualities? When they all look good on paper, how do you make a choice? How do you get past the résumé to perceive the person and, most important, predict the performance? To give some specific examples: Who would have predicted from the twenty-year tenure of David Pottruck at Schwab that he would fail so miserably as the handpicked, groomed successor to founder Charles Schwab? Or, similarly, that Doug Ivestor at Coke would fail when he followed the famed CEO Roberto Goizetta? How could organizations avoid hiring charismatic yet ultimately value-destroying leaders like Jeff Kindler, first at McDonalds and then at Pfizer?

An executive’s failure adversely affects many individuals and organizations. The company loses money: Firing an executive may incur legal and severance fees, the cost of recruiting and developing a replacement, and losses from interrupted schedules or abandoned projects. Dismissing a senior executive can cause upheaval and chaos among the company’s employees. It may even affect the board of directors if its members are personally blamed for the executive’s poor decisions. As productivity drops, the effect may trickle down to the company’s clients or suppliers, eventually hurting the surrounding communities. As we have seen in recent years, our economy tightly weaves together many seemingly unconnected business sectors.

Active Coping

As one approach to help organizations avoid the adverse effects of poor leadership, I have continued to develop the theory of active coping. The theory is explained more scientifically in other publications and in the technical companion to chapter 4 (appendix B).1 I also look individually at each element of active coping in chapters 5 through 8. Here, I describe it as it appears in everyday life.

Even if you have never heard the term, you know it when you see it. When a person always seems prepared and quickly recovers from any setback, that is active coping. When a person earns the trust of her friends and colleagues by refusing to take unfair advantage of others and refuses to let others take unfair advantage of her, that is active coping. When a person has the vision and self-confidence to rise above “business as usual” when necessary, that is active coping. When a person is open to the people around her, listens to bad as well as good news, and is aware of her own motivations, strengths, and shortcomings, that is active coping.

To many, the word “cope” has connotations of barely scraping by. I use it quite differently, to refer to a sense of mastery, an orientation to life. All human beings encounter difficulties on a daily basis, both internal (to the self) and external. We have intricate internal landscapes filled with drives, values, dreams, and ideals. Some are compatible and some are in conflict. “Coping” is how we reconcile and express these many parts of ourselves, endeavoring to bring into balance our internal needs and the external demands of our environment. Individuals can learn to master themselves and the circumstances that surround them, taking an active coping stance toward the world. Or they can be passive copers, allowing themselves to be defined by their circumstances and enslaved by their personal needs. When circumstances change unpredictably, an individual’s latent weaknesses—or untested strengths—emerge.

We all have to make an effort to achieve our goals. To do so, we usually have to solve problems and overcome obstacles. Some are created by our surroundings, some by other people, and some by who we are. Encountering these obstacles creates stress. When we take action—whether cognitive or behavioral—to reduce that stress, we are coping. Coping is part of the process of adapting to and even changing the environment.

When dealing with stress, a person can respond in one of four ways. The first is to identify the stress and remove it, maintaining—even improving—physical and emotional health. The second is to identify and tolerate the stress without changing it, keeping the status quo but not growing. The third is to defend against the stress by denying it, distorting the perception of it, or reacting to it in an unrealistic manner. The fourth is to suffer a complete breakdown in functioning. The first response is active coping. The second response is passive coping. The third response is neurotic, defensive coping. The fourth response accompanies personality disintegration.

What Is Active Coping?

Active coping is the healthiest response to stressful situations and the one most likely to lead to a successful resolution. It is like a car: We can manage to get where we need to go if we are driving an ordinary, inexpensive car, and we can make it through life with a less than optimal coping style. But driving a car with superb engineering is crucial if we are racing in the Indianapolis 500 and will get us farther, faster, with less likelihood of accident or breakdown in other situations. A strong framework of coping does exactly the same thing.

Active coping is the readiness, willingness, and ability to adapt resourcefully and effectively to novel and changing conditions. It is a stable, albeit complex psychological orientation across time and circumstance, a style of functioning, a continuous seeking for the most effective path through life. Think of it as a constant state of being “open for business” that springs from a healthy personality structure. It comes into play in the now, at each moment of decision or challenge.

Individuals who are active copers strive to achieve personal aims and overcome difficulties rather than passively retreat or become overwhelmed. The psychological ammunition that active coping provides is extremely useful when determining the best way to respond to a situation that was not, or could not be, anticipated. Active copers feed on experience; they incorporate what they have learned into their psychological systems, making themselves increasingly capable of tolerating uncertainty and devising new strategies for growth. When they fail, they learn why and respond more effectively the next time. Rather than hide from constructive criticism, they seek it out as useful advice. This openness increases their effectiveness as leaders and, more generally, in life.

Active copers support others and take advantage of opportune moments to share what they have learned. They pass on their experiences not only to help others make similar improvements but to remind themselves of their own life lessons and reinforce their own growth. This tendency to teach and share is what motivates leaders to develop mentoring relationships, helping younger, up-and-coming leaders develop their own modes of active coping.

Whereas active copers seek to confront and resolve challenges, passive copers are reactive and avoidant. Passive coping is an inability to tolerate the full tension of a difficult situation. We have all seen examples of passive coping: the board member who reacts in crisis before the CEO can gather sufficient facts, the manager who lashes out at subordinates to relieve stress, or the friend who hides from tough decisions. Passive coping is retreating from reality, tuning out information, and resisting change. It’s dealing with minor problems in order to avoid confronting the anxiety of major problems. It’s rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. In business, active copers continue to build their understanding of industry dynamics and disruptive technologies and to anticipate economic changes; passive copers repeat what worked yesterday.

Active copers are not always successful. Any number of unexpected events—injury or illness, economic downturns, divorce, war, the competition, disruptive technologies—may undo good planning and resolute effort. Reality is essentially refractory. It gets in the way of what we want. Even when life does not throw up insurmountable barriers, we can fail. No one copes actively in every situation. We don’t expect perfection of those around us and shouldn’t expect it of ourselves. But knowing that sometimes our coping may falter, we can take steps to prevent it. Shoring up weaknesses is a part of active coping, too.

This book is about more than active coping in business, but it focuses on active coping in business leaders. Leaders, by the nature of their position, have to cope not only with their personal goals and frustrations but with the goals and frustrations of their followers and the group as a whole. To be effective and reliable, leaders must be capable of active coping. Leaders must be persistent; good leadership is not merely handling one problem effectively but handling a multitude of problems well and recovering quickly from setbacks with energy and determination to prevail. Leaders must also be flexible, able to adapt resourcefully and rapidly to current and potential crises. These qualities of flexibility, adaptability, creativity, and endurance are fundamental to active coping.

Active coping as an overall style of functioning enables us to meet the demands of the external world as well as our internal needs without letting one overwhelm the other. When we bring the two into harmony, we experience self-esteem, contentment, and happiness. When we adapt to the external world in a way that makes us feel good about ourselves, we get the energy to continue to grow and adapt.

Leaders who possess healthy, integrated personalities can tolerate the tension felt when handling challenges, threats, or conflicts. They can create and implement strategies to overcome challenges, deal with threats, and resolve conflicts. These strategies operate consciously and unconsciously in such a way that brings into balance environmental pressures and individual aspirations, needs, and values. This balancing act is particularly important for leaders because their functioning affects all who are touched by their leadership. A leader must be a whole person with strong active coping in order to meet the responsibilities of leading. Active coping is what we expect from leaders: the readiness and ability to learn, adapt, improvise, mobilize, and overcome conflicts. Leaders who possess these qualities are far more likely to be effective than those who do not.

Because leadership has long-term implications, my focus is on making long-term (e.g., three- to ten-year) predictions. I choose to look at coping not as a one-time effort but as a style, a constant state of readiness that supports healthy growth and adaptation over the course of a person’s life. Just as investors evaluate a company to understand its earning potential, I assess an executive or potential executive to predict his or her potential to grow and perform in a specific role.2 Identifying a candidate’s coping style forms the core of my evaluation process but not its full extent. My evaluation process also takes into account the interactions of the executive, the corporate strategy, and the operating environment. Each situation is unique, but knowing the effects of each component with a high degree of detail strengthens the ability to predict whether executives will perform as required.

Four Elements of Active Coping

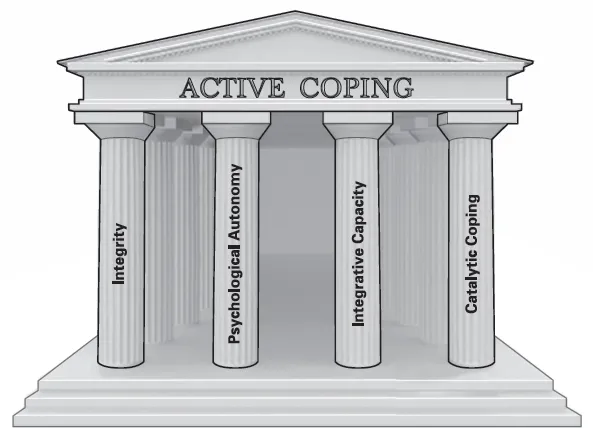

I developed the psychological model of leadership by studying both the theories behind the concept of active coping and the qualities required for effective leadership.3 I thought about what effective leaders did, felt, and thought; why they behaved as they did; why they made the decisions they made; and why those actions were effective—or not. I condensed these thoughts and theories down to create my personal definition of effective leadership: leadership is effective when it influences the actions of followers toward the achievement of the goals of the group or organization. Working with this definition, I identified four interconnected parts, four elements of the active coping style: integrity, psychological autonomy, integrative capacity, and catalytic coping. These elements seemed necessary to engender and sustain effective leadership.4

Integrity depends on the consistency of behavior in accordance with values and ideals.5 Leaders who demonstrate integrity earn the trust of their followers, their superiors, and the community. This trust allows them to function more efficiently because they don’t have to spend a long time getting acceptance and approval for each action they take. Lack of integrity causes leaders to act erratically because they are not strongly connected to a secure or consistent system of values. They are unreliable leaders, often favoring their personal whims over the interests of others, and may damage their organizations or communities by their selfish actions.

Psychological autonomy involves the ability to recognize and respect the aims and feelings of others while purposefully striving to achieve a goal or path. It is the ability to make and impose choices on the world—the opposite of groupthink. Psychological autonomy gives a person the freedom to choose the most effective course of action.6 Leaders with high psychological autonomy can respectfully disagree with their followers, their colleagues, and their superiors. They have the confidence to take an unpopular but necessary action and stand firm against doubt and disapproval. Conversely, those with low psychological autonomy capitulate to pressure from their subordinates, peers, and authority figures. They require the safety of consensus.

Integrative capacity is an ingrained ability, developed through practice, to draw together diverse elements of a complex situation into a coherent pattern. It is, literally, the capacity to integrate information from one’s self and surroundings into a new and greater understanding of the tapestry of life.7 Leaders with strong integrative capacity are aware of their emotions and motivations as well as their weaknesses. They have open minds, accepting input from all sources. Then they put together what they know about themselves with the realities of their situations to create a deep understanding of possibilities. Leaders with poor integrative capacity have a narrow focus, ignoring any information that doesn’t fit their limited worldview. They may have little awareness of their own motivations and states of mind and therefore fail to understand the motivations of others. They lack an understanding of mutuality. They deal with events one at a time, blind to the connections between them, unable to extrapolate into the future.

Catalytic coping is the ability to invent creative, effective solutions to problems and then carry them out. It is the most overt expression of active coping, the easiest to observe and measure. Leaders strong in catalytic coping always seem to have thought out several options to resolve each problem. If there isn’t an option, they create one. They develop detailed plans and execute them. That does not mean they are rigid; if conditions change and the plan ceases to be effective, catalytic copers immediately rethink their options and adjust the plan. Leaders who lack catalytic coping do not look, think, or plan ahead. If they come up with a plan, it often lacks depth or creativity. They will stick to it whether it suits current conditions or not. They seem lost when faced with difficult or unusual conditions and may fail to take timely action or any action at all.

These are not entirely different factors; they are elements of a whole style of being. If you wonder whether the four elements of active coping carry different weights in predicting leadership effectiveness or general adaptation to life, consider this analogy: Are there relative weights for the circulatory, respiratory, digestive, endocrine, and neurological systems of the body? One could argue that one system is more crucial than another—but the fact is that if any of those systems ceased to operate, the body would die. If any became relatively dysfunctional, such dysfunction would affect the entire body. In the same way, the four elements of active coping rely on one another to function effectively.

Another good analogy is a Greek temple—solid, stable, enduring. The building’s strong pillars support a wide triangular pediment and roof; intact, it can withstand nature’s onslaught for centuries. This iconic structure illustrates well how the elements of active coping are a crucial part of active coping as a whole. Each element—integrity, psychological autonomy, integrative capacity, and catalytic coping—is like a pillar. Each supports the active coping “roof,” which covers and encompasses them all. If one pillar is missing, the structure loses stability and strength. If more than two pillars are missing, the structure crumbles. But if all four pillars are in place, the structure will stand firm for many years. I look for this active coping structure when I am trying to identify executive candidates who will stand the test of time in a challenging position.

FIGURE 1.1 The Elements of Active Coping

Speaking directly about coping, the ultimate goal of successful adaptation and growth depends on the operations and interaction of the four elemental functions. Basically, a person has to take in stimuli (from the outer and inner worlds), make reality-oriented sense of those ...