![]()

Part I

![]()

1

THE WORLD OF CHOKYI DRONMA

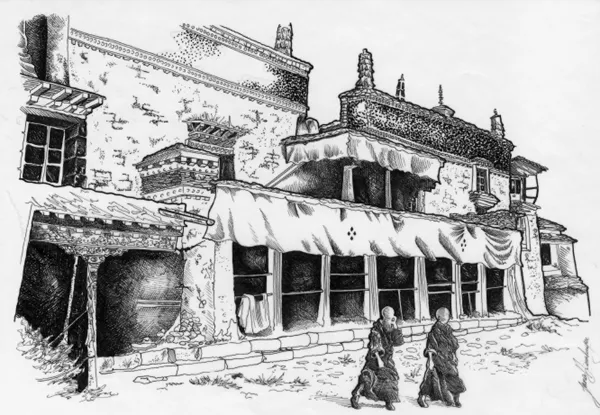

Nyemo, central Tibet, July 1996. Climbing a steep dirt road on foot, my daughter and I reach a small, somewhat decrepit monastery. The once-white walls rise from a mound overlooking a small stream and a grove of willows, surrounded by a flat sandy area. As we enter through the gate of the enclosure around the main building, a young monk, seemingly unused to foreign visitors, comes toward us. I ask him whether this is Nyemo Chekar. Surprised both by our arrival and by the question, he replies yes. The monastic compound is indeed surrounded by the chekar (bye dkar) or “white sand” to which it owes its name.

We have come from Samding monastery, where the head lama, Thubten Namgyal, told me about the Dorje Phagmo, the Princess of Gungthang who founded the lineage of female reincarnations in the fifteenth century; about the current reincarnation, who is the head of his monastery and a government cadre; and about how much of Samding and the tradition survived the Cultural Revolution. From the start of the monastery restoration, he has painstakingly pieced together salvaged manuscripts, ritual items, statues, relics, people, and memories. He even designed a set of mural paintings representing the various Dorje Phagmo reincarnations, based on his own recollections and a few ancient murals that had survived. A similar room, an old one at Chekar in Nyemo, has been his source of inspiration. Thubten Namgyal told us that the sixteenth-century Bodongpa monastery survived the Cultural Revolution because it had been transformed into a granary, so the mural paintings had been protected from major damage.

FIGURE 1.1 Nyemo Chekar monastery as it appeared in 1996. Jana Diemberger

My eleven-year-old daughter and I have been traveling along the Tsangpo, the Brahmaputra river, and through the lush and fertile valley of Nyemo while I try to complete a long overdue study of Bodong Chogle Namgyal and his tradition.1 In what would turn out to be an extraordinary coincidence, I had made the difficult decision to leave my one-year-old daughter at home with her grandmother.2

A group of welcoming and somewhat bewildered monks have gathered around us by the time we reach the porch of the temple. There we find what I have been searching for: portraits of the reincarnations of Dorje Phagmo, freshly painted in bright colors. We are told that the old paintings had been so damaged that the monks decided to repaint them. I am growing anxious. Perhaps it is too late, perhaps everything that was left has been covered by these pleasant but decidedly new images. I ask whether there are any other paintings of the Bodongpa tradition in the monastery. The monks show us into a dark altar room full of dust, broken statues, and ritual items in disarray, witnesses to a tragic history. As our eyes become accustomed to the darkness, we discern that the walls are fully decorated with remarkable portraits. With the help of a flashlight, I identify Bodong Chogle Namgyal, the deity Dorje Phagmo, and the blue horseman who is the protector of the Bodongpa tradition, Tashi Ombar. But there are no signs of anything that could represent the human forms of the Dorje Phagmo. After leading us through the dark rooms of the ground floor, the monks take us to the upper floor, where, over tea, they recount the history of the monastery, founded by an incarnation of the Dorje Phagmo called Nyendra Sangmo and by the Bodongpa spiritual master, Chime Palsang. We talk about my year-long research on the monasteries, shrines, and people of the Bodongpa tradition and the journey that led to Thubten Namgyal at Samding.

After tea, the monks lead us through the upper rooms. Piles of loose folios of manuscripts, probably recovered after the Cultural Revolution and still waiting to be sorted, speak of the current state of the monastery; the monks make no secret of the difficult conditions under which they are operating. One room, however, looks much better and seems to be where the small community practices rituals on a regular basis. There is a new statue of Bodong Chogle Namgyal, and a copy of the Buddhist canon neatly arranged on the bookshelves. Gradually we realize that this room is fully decorated and that there is a beautiful painting of the blue horseman just behind the door. I can make out small, somewhat rough and damaged images of Bodong Chogle Namgyal and Chokyi Dronma on the wall, but these are standard representations, not the historic, realistic images I have heard exist in this monastery. However, half hidden behind the books are numerous other images of all types: famous spiritual masters such as Bodong Chogle Namgyal and Chime Palsang, various Karmapas, and a number of women. One of them seems to be peeping out from behind the books; she has remarkably realistic features, full monastic robes, long black hair hanging loose over her shoulders, and earrings of gold and turquoise. Next to her are other, similar women, each with a distinctive outfit and expression. In the middle there seems to be a large image of the Shamar, the Red Hat Karmapa. The monks confirm that these are the paintings that the monks of Samding have recently used as models for their representations of the lineage. No names are written beside them but by comparing them with the new ones reproduced in the porch, which include the names, I can identify most of the women as different reincarnations of the Dorje Phagmo. The age of the monastery, the emphasis given to the Red Hat Karmapa and to Chime Palsang, and the number of Dorje Phagmo incarnations suggest they date from the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century. On this basis, the image of the woman we first saw through the books seems to be that of Chokyi Dronma, the Princess of Gungthang. At last we have found her—at least provisionally, since not all the mysteries of this painting are fully unraveled.

I returned to the monastery several times in later years and came to know the monks as part of the network of Bodongpa monasteries and nunneries that have tried to revive this tradition. Many of the great masters who led the early stages of its reconstruction, including Thubten Namgyal, have since died. But the 1996 visit to Samding and Nyemo remains one of my earliest and most remarkable direct encounters with the princess and her tradition. The picture of Chokyi Dronma with her royal jewels, the long hair of a yoginī, and the monastic robes of a nun seemed to epitomize the distinctive and conflicting features of her personality, which I would later come to know through her biography.

But where did she come from originally? At the western edges of the Tibetan plateau, the mountains rise to form a ridge surrounding a high, mostly arid expanse that provides a livelihood for nomadic herders and pastoralists. This area is intersected by deep river valleys inhabited by farmers. It is the region known to Tibetans as Ngari Khor Sum, after the three areas that constitute it and that touch what was, until the mid-nineteenth century, the independent Tibetan Buddhist kingdom of Ladakh to the west. In the easternmost of these three areas, in a fertile valley alongside one of the rivers that thread through the lower half of the plateau on their way to become the principal rivers of South Asia, Chokyi Dronma was born. Her father was the ruler of Gungthang, a separate kingdom that had been founded by a splinter of the ancient dynasty that ruled the Tibetan empire from the sixth to the ninth centuries. Therefore, in the eyes of her contemporaries and of later generations, she has represented not only Buddhist female sacredness but also the Tibetan imperial legacy.

A Glance at the Broader Historical Picture

Human presence on the Tibetan plateau dates back several thousand years (the most ancient finds, so far, suggest habitation some 40,000 years B.C.E.), but the archaeology of the region is still in its infancy and hardly anything is known of the people who lived there in prehistoric times (Chayet 1994:21ff.). At the dawn of recorded Tibetan history, around the sixth century C.E., the sources speak of a number of local polities that were unified under the kings of a side valley of the Brahmaputra river south of present-day Lhasa, known as Yarlung.

A royal myth—told in the most ancient of the extant Tibetan chronicles3 and in many later documents—tells how the first king descended from heaven by a rope of light and was welcomed by the representatives of these small kingdoms. He married a lumo (klu mo), a female deity of the underworld, and became the legitimate ruler of “the black-headed people,” as the Tibetans then called themselves. Each of the early kings returned to heaven after his mission on earth was completed, until one of them became involved in a fight that led to this rope of light being severed. The kings thenceforth became mortals: they died on earth. The custom of celebrating royal funerals and building royal tombs thus began. The Tibetan kings used to wear white turbans that recalled the rope of light and so reflected their divine origins and their special powers,4 upon which the prosperity of the whole country was thought to depend. Large tombs were established during this period in the ancestral region of the Tibetan kings, the Yarlung valley, south of the Brahmaputra River. This was where these kings ruled before relocating their capital to Lhasa around the middle of the sixth century.

Songtsen Gampo, who died in Lhasa in 649, is the most famous of the early Tibetan kings. He vastly expanded his domain through a series of conquests and is usually considered the dominant figure in the story of the Tibetan empire. He also acquired a highly symbolic importance: the invention of the Tibetan script, the legal code, and the introduction of Buddhism are traditionally attributed to him and his ministers, even though these were in reality lengthy and complex processes that stretched over a long period of time and involved other members of his dynasty. But there is no doubt that between the sixth and the ninth centuries the kingdom expanded to become a powerful empire that controlled much of Inner Asia and competed with the Chinese empire of the Tang dynasty farther north and east. Tibet’s foreign policy shifted back and forth between marriage alliances and war. Songtsen Gampo’s own marriage with the Chinese imperial princess Wencheng, in particular, became the most celebrated in later histories and epic cycles,5 and more recently, under Chinese influence, has been featured in innumerable songs, dances, plays, and films.

During the time of Songtsen Gampo and his immediate successors, Tibet experienced what is known as the ngadar (snga dar), “the early diffusion”—the introduction of Buddhism under the patronage of the king and other members of the ruling elite. The first Buddhist monastery was established at Samye in 779 at the orders of King Thrisong Detsen (742–797?), and many Buddhist texts were translated into Tibetan, mainly from Sanskrit, during his reign and those of his successors. In the ninth century the Tibetan empire began to disintegrate as a result of clashes among the ruling clans, especially between pro- and anti-Buddhist factions, which had increasingly come into conflict as Buddhist institutions had become steadily more powerful. When the extremely devout Buddhist King Ralpacen was murdered, Langdarma, who strongly opposed Buddhism, ascended the throne and initiated a persecution of Buddhist institutions that led to his own death in 842 at the hands of a now famous monk called Lhalung Palkyi Dorje, who has been identified by an eminent Tibetan historian as the abbot of Samye monastery (Karmay 1988:76ff.). Civil war erupted and the kingdom rapidly fragmented.

Very little is known of the subsequent period of internal conflicts and political fragmentation, which lasted about a century. A number of local polities, some of which had emerged from splinter groups of the former royal dynasty, gradually came to power, and their rulers became the new supporters of Buddhism. In the eleventh and twelfth centuries a significant number of scholars and translators, both Indians and Tibetans, traveled back and forth across the Himalayas, bringing about what is usually known as the chidar (phyi dar), “the later diffusion” of Buddhism. Indian and Tibetan religious masters like Atiśa, Rinchen Sangpo, Khon Konchog Gyalpo, Marpa, Milarepa, Phadampa Sangye, and Machig Labdron, to name but a few of the most renowned, together with their disciples, established religious centers that gained increasing cultural and political importance. During this period many practices were transmitted from India to Tibet that belonged to the tantric or later form of esoteric Buddhism, including the Anuttarayogatantra cycles centered on the cult of Cakrasaṃvara and Vajravārāhī. These were to have an important bearing on Chokyi Dronma’s life.

After the collapse of the empire, Tibet underwent a radical political and social change that saw the almost total eclipse of the ancient clans, some of which had originated from the confederation of small polities that had preceded the empire and continued to dominate the political scene during dynastic times.6 The religious centers that had emerged around the masters of the eleventh and twelfth centuries acquired a higher social and political profile, creating their own distinctive traditions and becoming influential among the competing interests that supported them. Eventually some of the religious schools forged or tried to forge alliances with Tibet’s powerful neighbors, the Mongols, who, by the thirteenth century, under Chinggis Khan and his successors, had become the major political force in Inner Asia.

One of the most important religious centers at this time was located at Sakya in southern Tibet, and it became the first to create a successful alliance with the Mongols when Sakya Paṇḍita (1182–1251) and his nephew Phagpa (1235–1280) joined with the Mongol emperor Kubilai (1215–1294) to establish what is known as the “Yuan-Sakya rule” over Tibet. This lasted approximately a century and brought about a reunification of Tibet as a single polity administered by a governor based at Sakya within the framework of the Yuan empire. Important administrative reforms, such as the reorganization of the population into “myriarchies” (groups of 10,000 people), were introduced, and the establishment of a postal service significantly improved communications. This period saw an extraordinary blossoming of Tibetan Buddhism that helped to unify Tibetans and Mongols in a common religious endeavor. Politically, however, there were ambivalent feelings about this arrangement in which Tibet was unified but subject to an outside power, even though the relationship between the Yuan court and Sakya was seen as that between a donor and a spiritual preceptor. These feelings were exploited by some of the Tibetan local rulers, who pleaded for a return to Tibetan customs; these ideas were strongly reflected in some of the contemporary literature.7

In 1352 Phagmodrupa Changchub Gyaltshen (1302–1364), the ruler of one of the administrative units located in the Brahmaputra valley southeast of Lhasa, was able to assert himself against the Sakya government, overthrow its rule, and gain supremacy over Tibet. Some scholars, such as Tucci, saw him as a sort of early nationalist:

[Phagmodrupa Changchub Gyaltshen] is undoubtedly one of the most rem...