![]()

1

THREE PHASES

As tube, tape, and disc are replaced by file, pixel, and cloud, the present moment in media history offers a vantage point for regarding video as an adaptable and enduring term that bridges all of these technologies and the practices they afford. At different times video has been different things for different people, and its history is more than a progression of material formats: cameras, transmitters and receivers, tapes and discs, decks that record and play them, digital files, apps and interfaces. It is also a history of ideas about technology and culture, and relations and distinctions among various types of media and the social needs giving rise to their uses.

Champions and detractors have projected onto video a succession of fantasies, both positive and negative, at various moments of its history.1 Like television, video has been perpetually renewed, reborn as new media in relation to older iterations made obsolete by the relentless forward march of technology. It is something of a law of new media that emerging technologies are regularly invested with their users’ hopes and fears, with expressions of their societies’ tensions, contradictions, and crises.2 I aim to represent a history of video that accounts for these expressions in their specific contexts from the early period of television to the present day, identifying three broad historical phases. These phases are marked by technological innovations such as videotape and streaming web video, but also by the ways in which video has been placed in relation to other media, including radio, television, sound recording, and film, as well as networked computers, their hardware and software.

In the first phase, the era of broadcasting’s development and penetration into the mass market, video was another word for television. The two were not distinct from each other. In the second, TV was already established as a dominant mass medium. Videotape and related new technologies and practices marked video in distinction to television as an alternative and solution to some of TV’s widely recognized problems. It was also distinguished from film as a lesser medium visually and experientially, though at the same time it was positioned as a medium of privileged access to reality. In the third phase, video as digital moving image media has grown to encompass television and film and to function as the medium of the moving image. These phases are defined in terms of their dominant technologies (transmission, analog recording and playback, digital recording and playback) but more importantly by ideas about these technologies and their uses and users.

Video Revolutions is concerned with outlining the phases, but it also offers the example of video history as a way into reconsidering the idea of a medium as such. I propose adopting a particular understanding of this concept, a cultural view. From this perspective, a medium is understood relationally, according to how it is constituted through its complementarity or distinction to other media within a wider ecology of technologies, representations, and meanings. A medium is, furthermore, understood in terms not only of its materiality, affordances, and conventions of usage, but also of everyday, commonsense ideas about its cultural status in a given historical context. Cultural status refers to the ways in which a medium (or any cultural category or artifact) is valued or not valued, made authentic or inauthentic, legitimate or illegitimate.3 The medium of video exists not only as objects and practices, but also as a shifting constellation of ideas in popular imagination, including ideas about value, authenticity, and legitimacy.4 We can apprehend video’s materiality and its significance only through the mediation of discourses of video technology and the practices and social values associated with it.

I will be most concerned in my discussion of video’s three phases with describing and explaining each way in which video has been understood historically, particularly in terms of cultural status. When video was synonymous with television, its cultural status was television’s cultural status. When video was distinguished from television, its cultural status was opposed to television’s, unless it was associated with TV rather than with the movies that were the content of videotapes offered for rent at video stores. And as video has become a category bigger than either movies or TV, its cultural status has still been the product of enduring ideas about these media and their value and legitimacy. In my conclusion I will return to a more abstract discussion of the medium as a concept, elaborating on the examples offered from video history and extracting higher-level meanings from them.

In considering video’s history I have relied in particular on sources that speak to the ways in which people have understood popular media and culture. Reading the popular and trade press and the writings of prominent intellectuals and looking at advertisements and newspaper or magazine illustrations does not give us direct access to anyone’s thoughts, but it does establish a horizon of meanings available to individuals and communities in a particular place and time. It also shows us what some dominant meanings were, and how powerful interests tried to assert particular kinds of values and ideals. It is these dominant and typical available meanings that most interest me, as they speak most directly of video’s cultural status.

One key insight throughout will be the centrality of one medium in particular in relation to video. No matter whether video has been associated with television or distinguished from it, TV’s cultural status has often been the most important factor for understanding video. Television’s place as society’s dominant medium, and its shifting fortunes over time, will never be far from the surface in the events to come. Since television’s ascent to mass medium status, all media have been in some ways defined in relation to it. In the next chapter, the story begins with video and television sharing an identity in a period of optimism and hope for the future of communication, broadcasting, and the moving image.

![]()

2

VIDEO AS TELEVISION

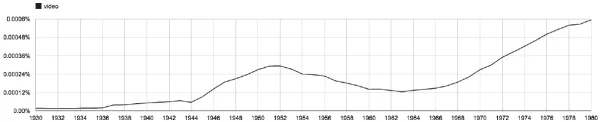

When television was new, the term video distinguished it from radio, a similar sounding word, out of which television grew as a commercial medium of broadcasting, and against which it was understood as a technological improvement. In the 1940s and 1950s, TV was synonymous with video, and the five-letter word fit well in newspaper headlines, where it often appeared in stories about broadcasting. This persisted for several decades, though the peak of interchangeable usage was in the early 1950s, as Google’s Ngram for video in American English sources suggests. Video’s bump in the early 1950s coincides with the emergence of TV as a mass medium. (The upward slope beginning in the later 1960s suggests that the term gained wider usage later on when it would distinguish video recording from live television broadcasting; fig. 2.1.) The New York Times broadcasting column in these early days of TV was called “Radio-Video.” Articles in the popular and trade press would use video the way we might today use TV, referring to video cameras, video stations, video sets, video studios, video personalities, video programs, video technique, and video audiences. When sponsors left radio for television in the early 1950s, the news reported this in terms of “video’s impact on radio.”1

FIGURE 2.1 Google’s Ngram for video (case sensitive) in English from 1930–1980.

Video in this phase was not only distinct from radio but also parallel to it. Radio referred to the transmission of sound via electromagnetic waves to receivers, most typically in the home in the case of commercial broadcasts. Video did the same thing, using similar technologies (e.g., transmitters and receivers), but with pictures. Orrin Dunlap’s 1932 volume The Outlook for Television notes that the vision half of the word television comes from the Latin video, “I see.”2 The earliest quotation in its OED entry, from a 1937 issue of Printer’s Ink Monthly, defines video as “the sight channel in television, as opposed to audio.” Thus the substitution of vi for ra in the words video and radio indicate a common meaning of instantaneous communication across significant distance of an electronic signal, and of commercial broadcasting. Calling the television a set indicates an aggregation of technologies, and video reception and display was one of these.3 At the time of TV’s introduction to the consumer market, the New York Times described how television works by explaining that the “video component” of a TV signal was composed of the broadcast of scan lines beamed by an electron gun. This would be joined by a sound channel, as in radio, a separate signal from the image or video channel.4

Television’s cultural status in its early years was a product not only of how TV was made and watched but of the hopes for the new medium and its idealization as a technology with the potential to overcome some of the deficiencies of existing media. Most centrally, the ideal of television was as a medium of immediacy and directness, making possible the instantaneous transmission of events bringing widely dispersed audiences together. Because of its place in the home and the size of its screen, and because of its status as an improvement on radio, television was regarded as an intimate medium capable of conveying honest and true representations to the individual viewer. And because of its addition of image to sound, television was seen as the culmination of decades of technological effort to transmit events live from one place to another, making possible a form of communication distinct and in some ways more impressive than earlier forms such as theater, movies, and radio. The fact that television’s picture was regarded as wanting in comparison to cinema’s helped promote the newer medium’s liveness and immediacy as particularly televisual aesthetic virtues.5 Early television was thus understood in relation to these forms in particular, and often in rather techno-utopian terms. Gilbert Seldes claimed in 1950 that by combining “sight and sound immediacy” with color and eventually stereoscopic images, TV promised to become a “platonic ideal of communication.”6

The techno-utopian connotations of television were among the meanings associated with the new medium in Captain Video and His Video Rangers, a notable early television program, which aired nightly at 7 P.M. on the DuMont Network from 1949 to 1955. A science fiction series broadcasting live on a modest budget, Captain Video might often be remembered as much for its laughably cheap production values and its commercial appeal to children as a market for tie-in merchandise like space toys and apparel as for the ideas it expressed about the video medium. But as David Weinstein argues, Captain Video represented post–World War II ideals of belief in the application of scientific knowledge as a way of overcoming the devastating military struggles of the past, represented in the figure of the Captain as a space explorer and fighter.7 By naming the character after the medium on which he appeared, the show’s creators were not merely establishing an identity for Captain Video as a TV personality and drawing on the novelty of TV. The Video in his name also spoke of the potential for television to be part of a new world of scientific progress and exploration. In these years when television was new enough to be considered magical, like something out of the world of science fiction, TV representations of space and of the futuristic gear of space travel (actually refashioned from Wanamaker’s department store stock such as automotive parts) implicitly conveyed the medium’s power to overcome old limitations of time, space, and vision. Within the narrative of the program, Captain Video communicates via an antenna atop his house, employing one tool called the “opticon scillometer,” a telescope-like device that gives him the power to see any and all things, and another called the “remote carrier beam,” a display resembling a TV set that permits communication with his agents in remote locations. Video, as repurposed in this representation, was not merely an improvement on radio but a revolutionary and futuristic technology leading toward human achievement and progress. Its power of making seen the unseen and connecting people across vast distances was connected to its mission of establishing institutions of commercial broadcasting, which was the ambition of early networks such as DuMont. Thus liveness and associated ideals promoted as TV’s essential qualities were not merely technical descriptions but also expressions of hopes for a new technology growing alongside hopes for postwar society.

These ideals were also figured in relation to other media and their institutions, typically understood in terms of their own social implications and the anxieties associated with them. The liveness and instantaneity of TV gave video its earliest identity, and it was one constructed in opposition to the dominant mass medium of entertainment in the years leading up to TV’s introduction: the movies, which meant Hollywood. As William Boddy has shown, critics of the early 1950s regularly opposed television’s aesthetics with cinema’s, and the contrast was based not only on technological criteria but also on the reputation of the movies and the American film industry.8 In the account of cultural elites, Hollywood was characterized by its cynical assembly line production of mediocre entertainment for an undiscerning mass audience. Television, they hoped, would do better by avoiding the conformity and commercialism of the movies and upholding a higher artistic standard in its programming. Video was idealized in terms of cultural uplift ...