eBook - ePub

Frankenstein

About this book

James Whale's Frankenstein (1931) spawned a phenomenon that has been rooted in world culture for decades. This cinematic Prometheus has generated countless sequels, remakes, rip-offs, and parodies in every media, and this granddaddy of cult movies constantly renews its followers in each generation. Along with an in-depth critical reading of the original 1931 film, this book tracks Frankenstein the monster's heavy cultural tread from Mary Shelley's source novel to today's Internet chat rooms.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Film & Video1

WELCOME TO NIGHTMARE THEATRE: MEETING FRANKENSTEIN

If a cult is anything, it has rituals and ceremonies and a schedule of worship. And here is ours: Friday nights, gathered in somebody’s basement, sleeping bags staked out on the floor. There are chocolate-bar wrappers scattered around and a half-eaten bag of Fritos waiting to be finished off. This is 1970, or possibly 1971 or 1969, and as twelve-year-olds our beverage of choice is something innocuous, Kool-Aid or Coke. It’s almost 11:30, so the parents have already looked down a final time and said their goodnights, and the lights are appropriately low. If anybody managed to smuggle in an issue of Playboy it’s been put away, because we need to concentrate on television now. There’s a plaster Madonna looming in a corner, that home icon of the Catholic family, which is apt because we are gathered here for something like a religious ceremony ourselves.

The local 11 o’clock news programme on KIRO-TV, Seattle’s channel 7, is ending. As always, the broadcast signs off with an editorial comment from station manager Lloyd E. Cooney, a bespectacled square perpetually out of step with the turbulent era (channel 7, owned by the Mormon Church, is a conservative business). Strange, then, that every Friday night Cooney’s bland homilies are immediately replaced by a dark dungeon, a fiend in a coffin and three hours of evil.

At 11:30 sharp comes ‘Nightmare Theatre’, a double feature of horror movies. Each film is introduced by channel 7’s resident horror-movie host, known as ‘The Count’ (actually a station floor director named Joe Towey). His make-up is a Halloween-costume version of Dracula, with cape and fangs. He clambers out of a coffin, welcomes us, and introduces the first feature of the evening; his Bela Lugosi accent is terrible, but his maniacal laughter is accomplished.

Tonight it’s that most famous title of all, Frankenstein (1931). The film is already legendary in my mind – I am well aware of its status in the horror pantheon. I have seen that green-faced, heavy-booted image in books and TV shows (though I am still somewhat confused about whether ‘Frankenstein’ is the name of the monster or the name of the mad scientist), and finally I am allowed to stay up late enough to watch the film on television. Here with other like-minded fifth-graders, I await the arrival of something monumental and, with luck, terrifying.

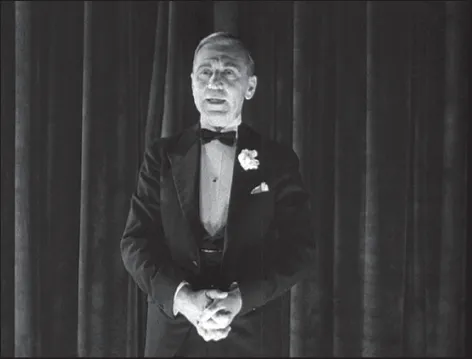

The Count finishes his intro with a cackle. When the film begins, it too has a host, a neat little grey man who comes out from behind a curtain and delivers a message that sounds both sinister and whimsical:

Mr. Carl Laemmle feels it would be a little unkind to present this picture without just a word of friendly warning. We are about to unfold the story of Frankenstein, a man of science who sought to create a man after his own image without reckoning upon God. It is one of the strangest tales ever told. It deals with the two great mysteries of creation – Life and Death. I think it will thrill you.

Edward Van Sloan, conveying Mr. Carl Laemmle’s warning as Frankenstein begins

It may shock you. It might even horrify you. So if any of you feel that you do not care to subject your nerves to such a strain, now is your chance to… Well… we’ve warned you…

This is going to be good.

And here it comes: a clammy graveyard (ah, excellent start), tasty stuff about an abnormal brain, sensational lab scene in an electrical storm. Now the entrance of the monster: first a tease, then the horrible face. Can I stand to look at it? Yes. It’s weird but bearable. The Monster stomps and kills but also suffers, and the villagers go after him in a burning windmill. The End. The movie has delivered, and those of us in the room have lived through something. In childhood, staying up late to watch horror movies is a rite of passage, a test, a communal ceremony in which fears are met, endured, analysed. Nightmares will come, but that’s part of the ritual too (although my fears at bedtime tend more toward the Wolf Man, whose dexterity and ferocious claws are more threatening than the Frankenstein monster’s clomping brute strength). We have seen Frankenstein, and the Monster is ours – a hero, in a strange way.

I first saw Frankenstein almost forty years after it had been made, and by then it was firmly entrenched as a cult classic. (Can a movie that was an enormous box-office success and a permanent fixture in popular culture be called a cult film? I believe so, especially if we emphasise the religious overtones contained in the word ‘cult’. And Frankenstein may have many fans all over the world, but there is still something forbidden about it, something outside the main of respectable culture.) Even though I was coming to the picture as part of a second, or perhaps third, generation of fans, even though I had already read about the Monster and seen his image refracted in everything from Mad magazine to The Munsters, it still seemed fresh – and thanks to the peculiar intimacy of late-night television, that first experience was also deeply personal. Frankenstein belongs in a dark room, late at night. The moviegoers of the 1930s and 1940s who saw the film in theatres are the people that gave the Monster its first life, without question. (Mel Brooks, who would make a detailed parody of the mythos in his 1974 comedy Young Frankenstein, amusingly recalls his boyhood fear that – against all logic – the Frankenstein monster would somehow stomp its way to Brooks’s boyhood home in Brooklyn.) Yet it was the TV generation that turned the Monster and his ilk into icons, a generation crammed with future filmmakers weaned on late-night horror films (among them Steven Spielberg, Robert Zemeckis, Sam Raimi and Joe Dante).

What is it about Frankenstein, in particular, that seems to touch a nerve? Some of the issues are embedded in the celebrated book that inspired the film. Even if Hollywood jettisoned many of the Romantic complexities of Mary Shelley’s novel, the book nevertheless manages to grin out from beneath the streamlining and backlot sets. At the elemental level, surely Frankenstein gets to us because it is a story of birth – and of ‘giving birth’. The mystery of how we got here is one childhood draw. Another early childhood anxiety surrounds the realisation of death, and Frankenstein messes with the possibility of life after death; it even makes the process look scientific and achievable. How could children not be intrigued by the movie?

GLOW IN THE DARK

The warning delivered by Universal stock player Edward Van Sloan at the film’s beginning, however fruity its language, does announce the stakes: this is a story of the great mysteries of creation – Life and Death. The movie explicitly invokes a Creator, comparing Man’s power with that of God, notably in a famously censored line of dialogue after Henry Frankenstein’s successful experiment, when the ecstatic scientist exclaims, ‘Now I know what it feels like to be God!’ The film, of course, will punish Frankenstein for his hubris, but one wonders whether the excitingly portrayed creation myth is the one that sticks with viewers, not the dutiful reminder about Man’s reach exceeding his grasp.

Even in the pulp trappings of a Universal horror film, and even to a child (especially to a child), Frankenstein gives off the heady whiff of grandness, of something large at play. I think as a child I drew power from Frankenstein, the bigness of its reach, the bluntness of its argument. The Monster, a child like me, was still learning how to use his body, how to relate to his parent, how to live in a world that seems hostile; he was clumsy with social interaction (until Bride of Frankenstein [1935], hopeless with words), but capable of enormous strength. Yes, his raw, unfocused power was scary. But damned if you didn’t end up rooting for him at the end. He was Mary Shelley’s outcast, misunderstood, wandering in a hostile environment. The villagers with their torches, by contrast, looked like small-minded, ignorant rabble, quick to anger. Who wouldn’t gravitate toward the Monster?

There were other levels of identification for my fifth-grade self. Frankenstein and movies like it were frowned on by parents, teachers, and just about everybody who occupied a position of power over the average twelve-year-old. The battles lines were drawn, and we were on the side of the monsters. A strong sense of association with something outlaw, something officially disdained by mainstream culture, is almost always part of the cult movie experience, and the cult model was at play in that basement in 1970: we were the believers, hungry for the feeling of community that a cult bestows upon the enthusiast. Let the Establishment have its Sound of Music (1965) and Love Story (1970) – next week ‘Nightmare Theatre’ is showing The Curse of the Werewolf (1961) and Dementia 13 (1963).

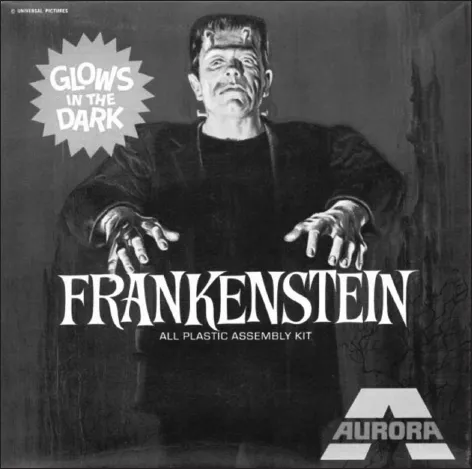

As in any cult, our worship needed objects and relics and a deeper system of belief. I cherished a coffee-table book by Denis Gifford, A Pictorial History of Horror Movies, which gathered together grisly photographs of countless movies I’d never seen or heard of. Soon I would get a model kit to build my own Frankenstein Monster – an activity that actually puts the user in the position of Frankenstein himself, of assembling different parts to make a creature, although here the pieces came not from a graveyard but from a nearby hobby shop. I also had a card game, ‘Monster Old Maid’, adorned with the Universal monsters. (The ‘old maid’ was Dracula’s daughter, in a particularly toothy grimace.) The gathering of talismans is another aspect of cult worship, and posters or magazines devoted to the monsters were an important part of extending one’s devotion. I laboured over the Aurora monster models and assembled most of the major characters: splashing nice red paint over the otherwise drab wrappings of the Mummy, painstakingly hanging the bats on the branches framing Dracula’s come-hither pose. This was the phase when Aurora was offering their ‘glow-in-the-dark’ versions of the monster models, with the somewhat bizarre effect of an otherwise realistically-painted Wolf Man crowned by a pale, light-green head. But it did glow in the dark, at least for a while.

Cover of Aurora’s first monster model, ‘Glow in the Dark’ version; cover art by James Bama

One might ask why an easily-frightened child would surround himself with these frightening images. (On the other hand, believers in Christianity favour the depiction of a man-god being tortured to death on a cross, so perhaps the leap for a Catholic schoolboy isn’t that far.) Keeping the monsters close at hand is surely a way to manage them, and the fear they represent. Here is an external representation of a child’s dread, kept near the bedside; when the child wakes up in the morning, it’s one more tiny victory over the forces of fear.

But the game was not an individual one. My friends also collected those monster models, which we could compare and contrast, and the communal viewings of ‘Nightmare Theatre’ were an important part of maintaining the enthusiasm for the monsters. This was the era before man had dominance over movies; an individual could not own a movie (unless you were some kind of 16 mm collector), and movies could not be rented. It was a random thing, and you’d have to check the schedule to see if one of the Universal titans was going to be showing that week. One of the hallmarks of ‘Nightmare Theatre’, which pulled its stock from a collection of films licensed for broadcast, was the crapshoot nature of watching it. Yes, you might get a goodie such as Bucket of Blood (1959), or an atomic giant-bug picture. But sometimes the gods were stingy. The schedule might list a promising title (The Man They Could Not Hang [1939] or The Frozen Ghost [1945]) and a bona fide horror star (Lon Chaney, Jr. or Boris Karloff), but the movie would play and the horror never came. These were the sleep-inducers, the price you paid for discovering the gems.

Frankenstein was in the regular ‘Nightmare Theatre’ rotation and thus aired every six months or so, as did other Universal 1930s classics, later Universal non-classics like The Thing That Couldn’t Die (1958), dubbed Mexican horror, and Roger Corman cheapies. Because of the hodgepodge nature of the schedule, one could see (entirely out of logical order) all of the original Universal Frankenstein pictures along with entries from the Hammer Films Frankenstein run, as well as such outré items as the drive-in schlocker I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957) and the Japanese Frankenstein Conquers the World (1965). Those early Frankenstein viewings blend together with the film’s sequels, which extended the story and increased the sense of a complicated mythos around the Monster.

This Frankenstein mythology had its constants, despite the wild variations in country of origin, time period, or quality. One constant was the name Frankenstein, a veritable ‘open sesame’ to all things horrific; the name was in the public domain, so anybody could take a crack at the concept. Universal copyrighted the classic make-up designed for Boris Karloff by Jack Pierce, an indelible image as familiar as the Coca-Cola logo – the flat-top skull and neck bolts, the distinctive black bangs. Yet those elements seemed to pop up everywhere, from cartoons (comic-strip and editorial) to advertisements; even the Monster stalking Japan in Frankenstein Conquers the World had the definitive Monster hairdo, like a piece of black Astroturf set outside a haunted house’s sliding door. Frankenstein’s Monster became a ritualised element, like a stock figure of Japanese drama. He might change his makeup, his geographical location, or his era, yet certain conventions would be in place; give a filmmaker a laboratory, some electric gizmos, and perhaps an abnormal brain, and he’s got himself a Frankenstein picture.

Every child wants order over chaos, and these elements provide a comforting sense of unity. The intricately-knit realm of horror films inculcates a notion of cinema as a world, a comprehensible universe. For children, the horror film is a seductive entrée to an idea of cinema because it creates a world that, while frightening, has rules. These rules (garlic, silver bullet, full moon) amount to a belief system, and this system applies not merely to individual films but the entire galaxy of horror pictures. There’s the sense of the cinema as an interlocking pattern of conventions and tropes, which can be compared across the spectrum of sequels and remakes (thus the busy chatter on horror movie website message boards, where the cultish details of horror – the good, bad, and obscure – can be parsed by like-minded enthusiasts).

For me that sense was enhanced by the recurrence of certain actors, most prominently Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi – even their exotic names sounded the gong of fear. The modern horror world was presided over by the likes of Vincent Price and Peter Cushing, who were almost as fine in their undertaker-like bearing. But lesser players, too, could be relied on to scurry from film to film: Edward Van Sloan, the fusspot vampire hunter from Dracula (1931), provided avuncular ballast to Frankenstein and The Mummy (1932) as well. Dwight Frye, an unfortunate lackey in Dracula and Frankenstein, would pop up in tiny parts in other shards of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Epigraph

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Welcome to Nightmare Theatre: Meeting Frankenstein

- 2. Assembling a Monster

- 3. The Monster Mash: Sons of the House of Frankenstein

- 4. Beyond the Clouds and Stars: Surveying Frankenstein

- 5. The Monster’s Place

- Appendix: The Frankenstein Family Tree

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Frankenstein by Robert Horton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.