![]()

1

Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood

Introduction and Overview

THOMAS RISSE

IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY, IT IS BECOMING increasingly clear that conventional modes of political steering by nation-states and international regulations are not effectively dealing with global challenges such as environmental problems, humanitarian catastrophes, and new security threats.1 This is one of the reasons governance has become such a central topic of research within the social sciences, focusing in particular on nonstate actors that participate in rule making and implementation. There is wide agreement that governance is supposed to achieve certain standards in the areas of rule and authority (Herrschaft), such as human rights, democracy, and the rule of law, as well as to provide common goods such as security, welfare, and a clean environment.

Yet the governance discourse remains centered on an “ideal type” of modern statehood—with full internal and external sovereignty, a legitimate monopoly on the use of force, and checks and balances that constrain political rule and authority. Similarly, the “global governance” debate in international relations, while focusing on “governance without government” and the rise of private authority in world politics (e.g., Cutler et al. 1999; O’Brien et al. 2000; Hall and Biersteker 2002; Grande and Pauly 2005), is based on the assumption that functioning states are capable of implementing and enforcing global norms and rules. Even the discourse on failed, failing, and fragile states centers on state building as the main remedy for establishing or restoring political and social order (see, e.g., Rotberg 2003; Rotberg 2004; Schneckener 2004; Beisheim and Schuppert 2007).

From a global as well as a historical perspective, however, the modern nation-state is the exception rather than the rule. Outside the developed OECD world, we find areas of “limited statehood,” from developing and transition countries to failing and failed states in today’s conflict zones and—historically—in colonial societies. Areas of limited statehood lack the capacity to implement and enforce central decisions and a monopoly on the use of force. While their “international sovereignty,” that is, recognition by the international community, is still intact, they lack “domestic sovereignty,” to use Stephen Krasner’s terms (Krasner 1999).

This book starts from the assumption that “limited statehood” is not a historical accident or some deplorable deficit of most Third World and transition countries that has to be overcome by the relentless forces of economic and political modernization in an era of globalization. Rather, we suggest that “limited statehood” is here to stay—even in so-called Western and modern societies—and that governance research has to take this fundamental condition into account. The book then asks how effective and legitimate governance is possible under conditions of limited statehood and how security and other collective goods can be provided under these circumstances.

The authors of this volume investigate the governance problematic in areas of limited statehood from a variety of disciplinary perspectives, including political science, history, and law. From a theoretical perspective, the volume challenges the conventional wisdom of the governance debate as being biased toward modern developed nation-states. Moreover, if we confront the central tenets of the governance debate with the empirical reality of historical or contemporary areas of limited statehood, serious conceptual and theoretical problems arise. If one of the key concepts of modern social sciences is not applicable to two-thirds of the international community, we face not only theoretical challenges but also eminently political and practical ones.

The authors probe the following assumptions: First, governance in areas of limited statehood rests on the systematic involvement of nonstate actors and on nonhierarchical modes of political steering, including bargaining and various forms of competition (see particularly chapters by Chojnacki and Branovic, Liese and Beisheim, Börzel et al., and Enderlein et al.). Yet these modes of governance do not complement hierarchical steering by a well-functioning state but have to provide functional equivalents to developed statehood (see chapters by Schuppert and Ladwig and Rudolf). Second, governance in areas of limited statehood is “multilevel governance,” which links the local with national, regional, and global levels and is based on shared sovereignty. This is fairly obvious in colonial governance as well as in modern “protectorates” where international and transnational actors provide governance services ranging from security to public authority (see chapters by Conrad and Stange, Ladwig and Rudolf, Schneckener, and Brozus). But it is also the case in many other weak states that the international community co-governs through the provision of collective goods and services (see chapters by Liese and Beisheim, and Enderlein et al.).

This chapter begins by introducing the book’s key concepts such as limited statehood and governance. I then discuss some conceptual issues that arise when governance is applied to areas of limited statehood. Drawing on the contributions to this volume, the next section highlights the contribution of nonstate actors in the provision of governance in areas of limited statehood. The chapter concludes by pointing to the “multilevel” features of governance in areas of limited statehood, in particular the role of external actors in the provision of collective goods and services.

Conceptual Clarifications

What Is Limited Statehood?

Our concept of “limited statehood” requires clarification.2 In particular, it needs to be strictly distinguished from the way in which notions of “fragile,” “failing,” or “failed” statehood are used in the literature. Most typologies in the literature and datasets on fragile states, “states at risk,” and so on reveal a normative orientation toward highly developed and democratic statehood and, thus, toward the Western model (e.g., Rotberg 2003; Rotberg 2004). The benchmark is usually the democratic and capitalist state governed by the rule of law (Leibfried and Zürn 2005). This is problematic on both normative and analytical grounds. It is normatively questionable because it reveals Eurocentrism and a bias toward Western concepts as if statehood equals Western liberal statehood and market economy. We might find the political and economic systems of the People’s Republic of China and Russia morally questionable, but they certainly constitute states. Confounding statehood with a particular Western understanding is analytically problematic, too, because it tends to confuse definitional issues and research questions. If we define states as political entities that provide all kinds of services and public goods, such as security, the rule of law, welfare, and a clean environment, many, if not most, “states” in the international system do not qualify as such. Moreover, such conceptualizations of statehood, which are more than common in the literature on failing and failed states, obscure what we consider the most relevant research question: Who governs for whom, and how are governance services provided under conditions of weak statehood?

Thus, we have deliberately opted for a rather narrow concept of statehood. We follow rather closely Max Weber’s conceptualization of statehood as an institutionalized rule structure with the ability to rule authoritatively (Herrschaftsverband) and to legitimately control the means of violence (Gewaltmonopol, cf. Weber 1921/1980; on statehood in general see Benz 2001; Schuppert 2009).3 While no state governs hierarchically all the time, states at least possess the ability to authoritatively make, implement, and enforce central decisions for a collectivity. In other words, states command what Stephen Krasner calls “domestic sovereignty,” that is, “the formal organization of political authority within the state and the ability of public authorities to exercise effective control within the borders of their own polity” (1999, 4). This understanding allows us to strictly distinguish between statehood as an institutional structure of authority and the kind of governance it provides. The latter is an empirical not a definitional question—for example, control over the means of violence is part of the definition. Whether this monopoly over the use of force actually provides security for the citizens as a public good and is irrespective of one’s race, gender, or kinship becomes an empirical question. Whether a state’s polity is democratic and bound by human rights also concerns empirical issues that should not be confused with definitional ones.

If statehood is defined by the monopoly over the means of violence or the ability to make and enforce central political decisions, we can now define more precisely what “limited statehood” means. In short, while areas of limited statehood still belong to internationally recognized states (even the failed state Somalia still commands international sovereignty), it is their domestic sovereignty that is severely circumscribed. Areas of limited statehood concern those parts of a country in which central authorities (governments) lack the ability to implement and enforce rules and decisions or in which the legitimate monopoly over the means of violence is lacking, at least temporarily. The ability to enforce rules or to control the means of violence can be restricted along various dimensions: (1) territorial, that is, parts of a country’s territorial spaces; (2) sectoral, that is, with regard to specific policy areas; (3) social, that is, with regard to specific parts of the population; and (4) temporal. It follows that the opposite of “limited statehood” is not “unlimited” but “consolidated” statehood, that is, those areas of a country in which the state enjoys the monopoly over the means of violence and the ability to make and enforce central decisions. Thinking in terms of configurations of limited statehood also implies thinking in degrees of limited statehood rather than using the term in a dichotomous sense.

This conceptualization allows distinguishing among quite different configurations of limited statehood. As argued earlier, “limited statehood” is not confined to failing and failed states that have all but lost the ability to govern and to control their territory (Rotberg 2003; Rotberg 2004; Beisheim and Schuppert 2007; Schneckener 2004). Failed states such as Somalia comprise only a small percentage of the world’s areas of limited statehood. Most developing and transition states, for example, encompass areas of limited statehood as they only partially control the instruments of force and are only partially able to enforce decisions, mainly for reasons of insufficient political and administrative capacities. Brazil and Mexico, on the one hand, and Somalia and Sudan, on the other, constitute opposite ends of a continuum of states that contain areas of limited statehood. Moreover, and except for failed states, “limited statehood” usually does not obtain for a state as a whole but in “areas,” that is, territorial or functional spaces within otherwise functioning states in which the latter have lost their ability to govern. While the Pakistani government, for example, enjoys a monopoly over the use of force in many parts of its territory, the so-called tribal areas in the country’s northwest are beyond the control of the central government and, thus, areas of limited statehood.

It also follows that limited statehood is by no means confined to the developing world. For example, New Orleans right after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 constituted an area of limited statehood in the sense that U.S. authorities were unable to enforce decisions and to uphold the monopoly over the means of violence for a short period of time. However, this book concentrates mostly on cases in which limited statehood in an area’s territorial, sectoral, or social dimension extends over sustained periods of time. For example, the chapter by Chojnacki and Branovic on markets of violence deals empirically with territorially and socially defined areas of limited statehood in mostly sub-Saharan Africa, where the state monopoly over the use of force is systematically lacking. The chapter by Liese and Beisheim focuses on areas of limited statehood in the developing world according to their territorial, sectoral, and social dimensions. The chapter on South Africa by Börzel et al. concentrates on policy sectors in which the South African state does not have the capacity to implement and enforce its own laws.

Moreover, if we conceptualize limited statehood in such a configurative way, it becomes clear that areas of limited statehood are an almost ubiquitous phenomenon in the contemporary international system and also in historical comparison (see the chapter by Conrad and Stange). After all, the state monopoly over the means of violence has only been around for a little more than 150 years. Most contemporary states contain “areas of limited statehood” in the sense that central authorities do not control the entire territory, do not completely enjoy the monopoly over the means of violence, or have limited capacities to enforce and implement decisions, at least in some policy areas or with regard to large parts of the population. This is what Somalia, Brazil, and Indonesia but also the People’s Republic of China have in common and share with modern protectorates such as Afghanistan, Kosovo, or Bosnia-Herzegovina—internationally recognized states that lack “Westphalian sovereignty” in the sense that external actors rule parts of their territory or in some policy areas (Krasner 1999).

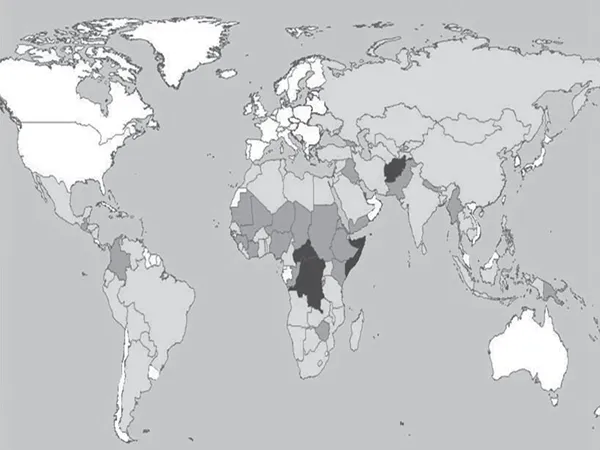

The following map presents a graphical description of the phenomenon. It uses a combination of two indicators of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) measuring degrees of, first, the state monopoly over the means of violence, and, second, basic administrative structures.4 The countries marked in white are fully consolidated states located in the Western world, as well as a handful of others, such as Chile. On the opposite end of the spectrum, we find twenty-nine failed (marked in black) or fragile (marked in dark gray) countries, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. The remaining countries (marked in gray)—the vast majority of states in the contemporary international system—contain areas of limited statehood in the sense defined earlier. Note that about 80 percent of the world’s population lives in or is exposed to such areas of limited statehood.

These data have serious consequences for the way in which we think about statehood in general. What if the modern, developed, and sovereign nation-state turns out to be a historical exception in the context of this diversity of areas of limited statehood? Even in Europe, the birthplace of modern statehood, nation-states were only able to fully establish the monopoly over the use of force in the nineteenth century (Reinhard 2007). And the globalization of sovereign statehood as the dominant feature of the contemporary international order only took place in the 1960s, as a result of decolonization.

FIGURE 1.1. Degrees of...