![]()

1

Introducing the Masses

VIENNA, 15 JULY I927

1. SHOOTING PSYCHOSIS

There was no question of issuing any warning before the firing started. The panic, which now arose, is beyond description.

At eight o’clock in the morning of the fifteenth of July, 1927, Vienna’s electricity workers switched off the gas and electricity supply to the city.1 Public transportation, communication, and production came to a complete halt. It was a signal: People left their work places and living quarters and began marching toward the parliament. Joining them halfway was Elias Canetti, later to become one of Austria’s most distinguished writers and a Nobel laureate: “During that brightly illuminated, dreadful day,” he wrote, “I gained the true picture of what, as a crowd, fills our century”2

The march was sparked by a court judgment concerning a killing that had occurred on January 30 of the same year in Schattendorf, a village in Austria’s Burgenland near the Hungarian border.3 A group of social democrats had marched through town. Throughout the 1920s, such manifestations took place almost every Sunday in nearly every town and village of Austria, a country split between the socialist movement and that of radical conservatives supporting the governing coalition and often organized in the local defense corps, the Heimwehr. As the Schattendorf social democrats passed the tavern of Josef Tscharmann, the watering hole for a gang of right-wing vigilantes called the Frontkämpfer, the Front Fighters, rifles were fired from a window. Matthias Csmarits, a worker and war veteran, and Josef Grossing, an eight-year old boy, were shot in the back and killed.

On the fourteenth of July, the jury of the district court in Vienna pronounced its verdict. The accused were the two sons of the innkeeper, Josef and Hieronymus Tscharmann, and their brother-in-law, Johann Pinter, all members of the Frontkämpfer. It was incontestable that they had fired at the demonstrators. They had confessed this themselves. It was incontestable that two people had died. The verdict of the jury was “not guilty”4

“A Clear Verdict” declared the Reichspost, the organ of the governing party, the following morning. “The murderers of the workers acquitted” ran the first-page headline of the Arbeiter-Zeitung, the major social-democratic newspaper, which published a fuming editorial by Friedrich Austerlitz. “The bourgeois world is constantly warning of a civil war; but is not this blatant, this provocative acquittal of people who have killed workers, for the reason that they were workers, already by itself a civil war?”5

Austerlitz expressed the sentiments of the working classes in Vienna, and this day they acted in accord with their passions. Their demonstration was not preceded by planning or announcements. It caught the leaders of all political parties off guard.6

The immediate goal of the workers was to voice their dissent in front of the parliament. Before reaching their destination, they were struck down by mounted police. Many began to arm themselves with rocks and sticks (see figure 1.1). The police responded by making arrests and brought the captured to their quarters on Lichtenfelsgasse. Demonstrators next attacked this station to force the release of the detained, overpowering the police and setting the building on fire. Meanwhile, the police had lined up outside the nearby Palace of Justice, on the assumption that this symbolic seat of the law was the demonstrators’ primary goal but not realizing that, by now, the police force itself had become the target. Attacking the police chain, the demonstrators besieged the Palace of Justice and forced their way into the building, some carrying containers with gasoline.

At 12:28, the fire department received the first emergency call from the flaming Palace of Justice (see figure 1.2). Fire engines were promptly dispatched, but the crowd—its number now exceeding 200,000—refused to let the vehicles pass. The chief of state, Ignaz Seipel, and the chief of police, Johann Schober, decided to arm 600 officers with rifles and gave them order to march toward the turmoil. Around 2:30, just as the demonstrators had yielded way to the fire engines, the police started shooting. By this time, Otto Bauer, the leading theorist of Austro-marxism and chairman of the Social Democratic Party, had reached the site:

FIGURE 1.1 Mounted police fighting violent demonstrators with cobblestones and sticks, Vienna, 15 July 1927. Unidentified photographer. Source: Austrian National Library. ÖNB/Vienna. 449671-B.

FIGURE 1.2 The burning Palace of Justice, Vienna, 15 July 1927. Unidentified photographer. Source: Austrian National Library. ÖNB/Vienna. 229.324-B.

I and some of my friends saw the following. A lineup of security officers progressed from the direction of the opera toward the parliament, a true lineup, one man beside the other separated by one to two and a half steps. At this time Ringstrasse was empty and only at the other side of Ringstrasse a couple of hundred people were standing, not demonstrators but curious onlookers who had been watching the burning Palace of Justice. Among them were women, girls, and children. Then one unit approaches, I saw them move forward, rifles in hand, persons who for the most part had not learned to shoot, even when firing they leaned the butt against their belly and fired left and right, and if they saw any people—there was a small group in front of the building of the School Council and a larger one in the direction of the Parliament—then they fired at them. The people were seized by frantic fear; for the most part, they had not even seen the unit. We saw people running away in blind fear, while the guards were shooting at them from behind.7

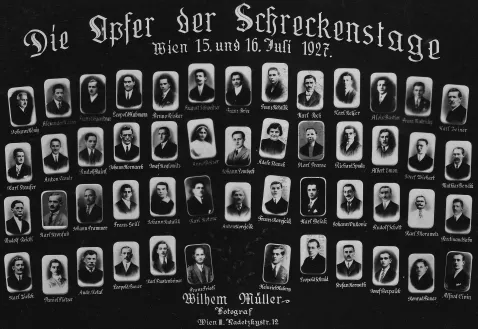

Gerhard Botz, the principal historian of the July events in Vienna, speaks of a “shooting psychosis.”8 The police shot demonstrators, spectators, and their own. They fired at men and women, at children and the elderly, at fire engines and ambulances. When calm was restored, eighty-five civilians and four police officers had been killed, and more than one thousand people were injured (see figure 1.3). One of the responsible officials, vice chancellor Karl Hartleb, admitted that the scene sometimes looked like a rabbit hunt.9 It was soon revealed that the ammunition distributed to the officers were so-called dumdum bullets, with uncased noses designed to expand upon contact with the target. The doctors attending to the wounded in Vienna’s hospitals related horrendous sights of bodies with wounds that appeared to have been inflicted from a distance of less than one meter.10

FIGURE 1.3 “Victims of the Day of Horror” Postcard commemorating about half the victims of police violence on 15 July 1927 in Vienna. Source: Collection of Stefan Jonsson. Copyright 1927: Fotograf Wilhelm Müller, Vienna. Photo: David Torell.

It was a price worth paying for the restoration of order, the bourgeois establishment of Austria believed. The Automobile Club of Austria expressed their gratitude by donating 5,000 schillings to the police. The chief of police likewise received financial compensation from the Association of Bankers, the Central Association of Industry, and the Chamber of Commerce. The Grand Hotel in Vienna reassured potential guests that the “unfortunate events”—“instigated by communists”—would in no way affect the comfort offered to foreign visitors. Dozens of police officers were decorated with medals of honor, tokens with which the upper classes encouraged the force that had protected their idea of society.11

Meanwhile, communists and left-wing social democrats believed that the July events were the sign of an imminent revolutionary situation. Soon, they thought, they would take advantage of the opening to realize their idea of society.

The fifteenth of July 1927 saw the breakdown of the democratic forms that had until then contained the political passions of Austria’s postimperial society. Created by the decree of the victors of World War I, the young republic was ruled by a Christian conservative government that had barely managed to stake a course through the postwar chaos. Thanks to the parliamentary cooperation of the social democrats, the government had resolved the crises caused by the destruction of the old Austro-Hungarian Empire, establishing between the working classes and the bourgeoisie a precarious equilibrium that held off the threat of civil war and gave the democratic institutions room to maneuver. July 1927 changed all this. From now on, the upper classes would associate the workers’ idea of a good society with the raging masses or the Bolshevik revolution, and these masses would see, in the burghers’ idea of a good society, the flashing muzzle of a gun.

Yet what emerged from the ashes of this class struggle was a vision of society that triumphed over both socialists and conservatives: a fascist front, superior to the socialists in mobilizing the people and better than the conservatives in maintaining social order. For the only force to truly benefit from the July events was the Heimwehr, the local militias. In order to consolidate the regime against the socialist threat, Austrian authorities, private donors, and the fascist governments of Italy and Hungary increased their financial and political support of this paramilitary force.12 The Heimwehr thus grew into a political force that could gradually realize its fascist ideal of an Austria purged of Reds and Jews. In sum, the fifteenth of July 1927 was a turning point in Austria’s history.13

2. NOT A WORD ABOUT THE BASTILLE

On Stadiongasse he jumped up on the heap of stones, which was there at the time, opened his coat, stretched out his arms widely, and shouted to charging security forces: “Shoot here, if you dare to!” And the unthinkable happened. The forces fired a volley at the defenseless man—covered in blood, he fell down on the stone heap.

“Fifty-three years have passed, and the agitation of that day is still in my bones,” Elias Canetti remarks in his memoirs. “It was the closest thing to a revolution that I have physically experienced. Since then, I have known quite precisely that I would not have to read a single word about the storming of the Bastille.”14 Canetti was so influenced by his experience that he spent the larger part of his life investigating the behavior of “the masses.” His investigation was not concluded until 1960, when he presented the results of his research in Masse und Macht (Crowds and Power), one of the most ambitious works of twentieth-century intellectual history, and maybe the most enigmatic.

If Canetti today is regarded as the very model of the solitary intellectual struggling to understand crowd behavior and collective delusions, we must not forget that his efforts were part of a collective undertaking. In political life as in social life, “the masses” has become a battle cry, wrote German theologian Paul Tillich in 1922.15 Virtually every thinker, writer, scholar, artist, filmmaker, and journalist of Weimar Germany and Austria’s first republic was preoccupied by or obsessed with the masses. All of them struggled with or against the masses. Some of them elaborated full-blown social theories and aesthetic programs, not to speak of political organizations and ideologies, on the basis of the social agent that they designated by that term. In all areas of interwar society, the mass was seen as the mother of all problems, if it was not seen as a promise of all solutions.

The masses? “No one could avoid encountering them on streets and squares,” writes Siegfried Kracauer in his history of the German film, recalling the situation after World War I. “These masses were more than a weighty social factor; they were as tangible as any individual. A hope to some and a nightmare to others, they haunted the imagination.”16 What was the nature of this agent? Why were “mass” and “crowd” deemed as fitting denominations for it? How come all branches of European art, culture, knowledge, and politics of this period worried so deeply about it? How come intellectuals and artists of no matter what background unanimously asserted that the masses, as novelist Alfred Döblin put it, were “the most enormous fact of the era?”17

The following pages will analyze, discuss, and explain the production and recycling of the category of the mass in interwar Europe. We will see that the mass functioned as a description of a certain social agent—an agent, however, whose true nature was highly disputed and whose location in the social terrain remained uncertain. But we will also discover that the mass was a political idea and an aesthetic fantasy, in some cases even an ontological category, without any firm denotation in reality.

The sheer ambiguity of the word goes some way toward explaining its frequency in the culture of the Weimar Republic and interwar Austria. In one magnum opus of Weimar sociology, Alfred Vierkandt lists all that was meant by the “mass” in the 1920s:

1. Mass = followers as opposed to leaders, 2. Mass = average people as opposed to those above the average, 3. Mass = lower strata (uneducated) as opposed to higher strata (educated), 5. [sic!] Mass = uprising or any temporary association as opposed to group, 6. Mass = association, class, social stratum, race, or the like, where often no distinction is made whether what is meant is a group (as a totality) or a series of similar individual beings forming something like a species, 7. Mass = temporary association of people in a state of strong excitement (as in ecstasy or panic), in which self-consciousness and higher spiritual faculties strongly regress (and without sign of any collective consciousness in the sense of a community).18

When someone spoke of “the masses” in the 1920s, the statement may have been an expression of common prejudice against the lower classes, but it may also have been an expression of social anxiety brought on by the war, the economic crisis, the appearance of women in public affairs, the rapid industrialization, or the bad times in general. Moreover, the statement may have carried a scholarly pretension of explaining the current state of affairs, but it may also have been used to voice social criticism, to confess the speaker’s utopian aspirations, to argue for urban renewal, to assert that history was headed on the wrong path and that the world had become a dangerous place, or to warn against the degeneration of the human species and the German race. Whether the word intended one thing or another depended entirely on the context and attitude of the speaker. The word could, in fact, mean one thing just as well as another, which is why—and Vierkandt stressed this point—so many speakers found it so useful and adequate for expressing whatever social views and opinions they held.

The first thing to realize about “the mass” as a term and about the masses as a social phenomenon in the interwar period, then, is that both were unclear and ambiguous. But the difficulty in asserting the meaning or nature of the mass should not be seen as a weakness on the part of those who spoke about the masses or as an error that could have been corrected by a more rigorous sociological and historical analysis. Instead of deploring or denying the contradictory references to the mass, the contradiction should be accepted, or even emphasized, as an indication and symptom of the historical predicament of interwar Germany and Austria. For the difficulty in defining the term reflects the greater difficulty in describing and representing the society that those who used the term sought to grasp. In the last instance, the conceptually confused and politically contested signification of “the mass” thus brings us face to face with a social and political crisis affecting the very mechanisms by which these societies sought to reconstruct themselves as coherent and meaningful political and cultural entities, thereby giving a meaning to their existence after the defeat and destruction suffered in World War I.

“In the 1920s, the...