![]()

![]()

4

Love came and began flowing like blood, under my skin, in my veins;

pushing my self out of me, it filled me up with the friend.

Now the friend has so gripped all parts of my being,

all that is left to me of myself is my name, the rest is all him.

—POPULAR SUFI QUATRAIN

In Persianate societies during the centuries that concern me, being a Sufi implied that one had come under the spell of love. This is readily evident in the period’s linguistic usage where words meaning lover and beloved are used ubiquitously to designate Sufis in prose and poetry alike. The ultimate object for Sufis’ love was God, after whose beauty poets such as the famous Jalal ad-Din Rumi pined away while lamenting their own shortcomings revealed as a consequence of their passion. By this period the accumulated corpus of Sufi writings in Arabic and Persian contained extensive discussions on the necessity of loving God, who was himself characterized as a being who loved his creation.1

While Sufi understandings of love for God have been the subject of a number of studies, much less attention has been paid to the fact that medieval Sufis also considered love to be the primary force underlying human beings’ intimate relationships with each other. Hagiographic narratives resound with the rhetoric of love as it pertains to human relationships, providing ample evidence that bonds based on love constituted the bedrock of Sufi communal life in these societies. My discussion in chapter 4 addresses this lacuna in our understanding by treating the general patterns as well as the social effects of the Sufi discourse on love as witnessed in literature produced during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The material I cover here is complemented by discussions to come in chapter 5 that complicate the idealized Sufi notion of love by paying attention to gender and the problem of seduction that may lead to non-Sufi ends.

The focus on love feeds into this book’s overall aim of using body-related themes to understand the functioning of Persianate Sufi communities in two ways. First, the question of love is front and center in the original sources, and highlighting stories that invoke the rhetoric of love conveys the overall social atmosphere that comes across when one reads hagiographic literature. Since love is intimately tied to corporeality in this context, uncovering the mechanics of love relationships provides a window into the imagination of the body. The second significance of love connects to the fact that human relationships described in terms of love produce obligations and expectations that are open to manipulation by those involved. The modulation of love relationships is intimately tied not only to affection but also to domination, submission, and control; concentrating on the way such relationships are represented in the sources provides a sense of the way power operated in a social milieu conditioned by Sufi ideas and practices.

The chapter is divided into sections that treat, successively, the bases, distinctive patterns, and social consequences of the medieval Sufi view of love. I begin by mapping out the general properties associated with love as a force and with lovers and beloveds as stock characters in Islamic discourses. This discussion centers on Persian poetic paradigms that acted as models for Sufi social relationships in the period. I argue that although medieval Sufi hagiographers relied heavily on the poetic rhetoric of love, their overall perspective on love saw it as something more than a fictional abstraction manipulated by poets to showcase their ingenuity. While poets’ ultimate aim was to highlight the nuances of characteristics associated with lovers and beloveds, Sufis used the poetic love tale to underscore forces that acted upon Sufis as they were striving to live up to their religious ideals. For Sufis the fiction of love as elaborated upon in Persian poetry acted as a kind of flexible script they utilized to articulate their mutual relationships.2

Hagiographies narrating the full life stories of major Sufis work through a cycle of love that I have divided into three phases. Persianate Sufis destined to achieve great spiritual and social status are most often shown to begin their paths in earnest when they fall in love with masters. Descriptions of these events rely heavily on the language of “love at first sight,” and, in a number of cases, the development of a relationship with a master goes hand in hand with coming of age and leaving the natal home. The middle periods of Sufis’ lives, when they are on the path but have not reached perfection, show them tormented by their passion for masters. Sufis in this phase of the love cycle actively seek to transcend their bodies and minds in order to unite with masters and, through them, God. Stories concerned with this phase show masters and disciples acting upon each others’ bodies in dramatic ways to exemplify uncontrollable passion and unexplained domination. The hagiographic love cycle ends when students become masters in their own right, attaining the aim of the most promising disciples. Fulfillment of this destiny is indicated in stories where the bodies of masters and disciples become indistinguishable from each other. This transmutation of bodies is the ultimate symbolic representation of the social mechanism through which groups of Sufis linked to each other through love might be understood as a single “social” body. Echoing themes discussed in chapter 3, this social body was both spread across space in the form of a community devoted to a specific religious path (tariqa) and continued beyond individual lifetimes through a Sufi intergenerational chain (silsila). The end of the chapter presents a work that argues that corporeal attraction is a necessity for falling in love and progressing along the Sufi path.

Stories of love that I retell in this chapter underscore the intensity of personal bonds between Sufis that ultimately guaranteed the cohesiveness of Sufi communities in the Persianate context. The primacy of corporeal exchanges in these stories indicates that the authors who produced them perceived the body as the primary locus of a person’s self, which had to be deployed strategically before other bodies for the sake of spiritual as well as social goals. To excel in the Sufi milieu in this period, a person had to be able to become the subject as well as the object of love. That is, Sufis who climbed all the way up the ladder of spiritual hierarchy to be regarded as friends of God did so by forming relationships with other Sufis in which they sometimes acted as lovers and at other times as beloveds. This interchangeability of Sufi masters’ functions within the context of love constituted one of the primary means through which they acted as powerful social mediators in the Persianate context.

THE PARAMETERS OF LOVE

Love in medieval Islamic literatures is considered a force known through its causes and effects. It is provoked by beauty, the hallmark of the beloved, which has a radically transformative effect on the lover. In lyric poetry the discussion of love takes place through the poet’s play on a number of stock characters, metaphors, and scenarios with which the reader is presumed to be familiar. Chief among the characters are love personified as an active agent, the lover, and the beloved, each of them invoked through well-known properties. Poets usually write in the voice of lovers, who ruminate on their own state and its cause, the force of love unleashed by the beloved’s beauty. Poets’ ingenuity lies in their ability to manipulate the established vocabulary of love with the aim of saying something familiar in a new way or highlighting a nuance hidden away within hackneyed metaphors.3 The essential framework of this poetic vocabulary of love can be summarized through a couple of representative examples from the Persianate context.4

In his narrative poem Sifat al-ʿashiqin (The Qualities of Lovers), Hilali Jaghataʾi (d. 1529) uses direct exhortation as well as aphoristic stories to highlight love’s status as the preeminent human emotion. After customary praises of God, Muhammad, and the art of poetry, he begins his discussion of love in earnest with the following eulogy:

The world is but a drop in the ocean of love,

heaven is but a plant in the desert of love.

There is no station higher than that of love,

its foundations are devoid of any flaw.

No vocation is better than the work of love,

no preoccupation greater than the madness of love.

One who is captive to love does not want release,

even when dying from sorrow, happiness is not what he seeks.

Worldly losses and gains are equally meaningless,

all that is there in the world is love, nothing else.

Although love would throw up everything in turmoil,

all liveliness in the world stems from its sorrow and pain.

No wilting ever comes to mar the spring of love,

passion’s wine never relinquishes its headiness.

Heart, throw yourself on the candle like a moth!

Become branded with its love mark, and burn!

Be the beggar of love, who nonetheless is the assembly’s king!

Go, be the sultan of your own times!

When love comes, do not be sad, sit happy;

feel yourself liberated from the world’s sorrows.5

Given the significance of love as described here, to be in love is a highly desirable state. The fact that love brings turmoil and pain to one’s life is deemed inevitable, but those who fall in love are urged to take the long view of the situation since they have, by virtue of being smitten, entered the most worthwhile arena of human experience. What is most significant about love is that it stirs up human beings in a way more potent than any other force that can act upon their bodies and minds.6

As already mentioned, poets usually write in the lover’s voice and portray themselves as victims of the beloved’s beauty. Their descriptions of the state of being in love decry the fact that they have fallen in love involuntarily, though, if the love is true, nothing in the world is able to pry them off from the beloved. While most words and actions described in poetry belong to lovers, beloveds are shown as the powerful party in the affair because their sheer presence grips the lovers’ mental states at all times. The following ghazal by Shah Qasim-i Anvar captures the contrast between the lover and the beloved as seen in this paradigm:

Of your beauty and comeliness, what can be said?

A cypress tree, an idol, tuliplike cheeks—what can be said?

You have etched sorrows and happiness on my heart’s page.

For what reason you have done so, my heart and life, what can be said?

We count ourselves among the dogs of your alley.

If you refuse to deem us one of them, what can be said?

Your sorrows we carry in our heart, day and night.

If none of ours finds a place in your heart, what can be said?

What is to be done with me: a heart-giver, a madman, a profligate!

Of your being a beautiful, heart-ravishing trickster, what can be said?

Upon remembering you my heart blooms like a fresh rose.

Of the qualities of such a spring wind, what can be said?

Friend, see, his work is to melt the heart of poor Qasim.

As to what may be the purpose of all this, what can be said?7

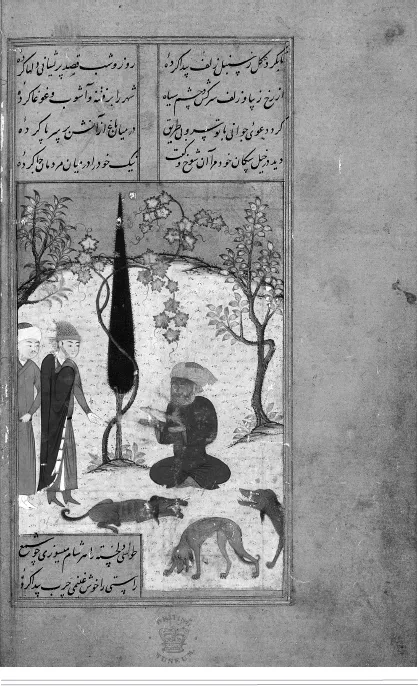

This ghazal contains common poetic themes, like the comparison between the beloved’s form and the cypress tree, the company of dogs, the beloved’s dismissive demeanor. These are also reflected directly in paintings, such as figure 4.1, which accompanies an anthology of poetry produced in Shirvan in 1468. The refrain “what can be said” (cheh tavan guft) in this poem is emblematic of the position of the poets/lovers, who feel unable to convey the full impact of the presence of the beloved upon themselves but are nevertheless compelled to speak of it endlessly. Beloveds are described in the form of entrancing pictures whose vision tethers lovers to them forever upon first sight. The greater a lover’s attraction to the beloved, the less he becomes bound by the mores of ordinary society. Although caught helplessly in this way, lovers are also marked by bewilderment as exemplified in the last verse of this poem: the initial attraction and the relationship’s eventual destiny are ultimately beyond rationality, so that there is no way for lovers to extract themselves from the situation by reasoning through it.8

The contrast of opposites between the lover and the beloved can be extended much further than what is given in this ghazal. Typically, lovers are active seekers while beloveds attempt to evade lovers’ attentions, lovers give voice to their longing in poetry while beloveds are usually silent, lovers’ bodies whither away due to self-neglect while beloveds are pictures of beauty and rude health, lovers are marked by frustration while beloveds are shown to be self-satisfied, and lovers are always in earnest while beloveds are playful and trivialize the attention directed at them. These differences between the two parties produce a constant tension that lies at the heart of the premodern Islamic rhetoric of love. The love relationship continues as long as this tension is unresolved; without it, love either dies or is consummated in a full union that leaves little to talk about. Classical Persian poets, masters of the rhetoric of love, play upon this tension to bring out the nuances of love relationships.

4.1 An ardent lover and a dismissive beloved from an anthology of poems by various authors. Shirvan, 1468. Opaque watercolor. Copyright © British Library Board. MS. Add. 16561 fol. 85b.

As in poetry, hagiographic narratives depict most connections between Sufis in the form of dyadic relationships between masters and disciples who have different roles and expectations assigned to them. In parallel with the discourse on etiquette discussed in chapter 3, these relationships mimic the kind of differentiation between the lover and the beloved described in poetry, which the hagiographers cite very frequently to make the point. However, poetry in its own context is different from Sufis’ use of poetry: in hagiography the overarching framework for Sufis’ interrelationships derives from Sufi socioreligious imperatives rather than poetic conventions. In poetry read without reference to a particular poet’s intentions within his context, the beloved is eternally beautiful, the true lover always hopelessly infatuated. Sufis progressing through their lives in hagiography are shown to occupy the positions of both lovers and beloveds at various points depending on periods of life and specific situations.

The mutability of Sufis’ position in the discourse of love is most clearly visible in extended hagiographies that narrate the whole life spans of particular masters. As young disciples, gifted Sufis find themselves in the position of lovers whose Sufi journeys begin when they become infatuated with older masters. As they become more mature, however, they increasingly come to occupy the position of their masters’ and others’ beloveds because of their future function as subsequent links in intergenerational chains of Sufi authority. This transformation has corporeal markers, as evident in the following anecdote about Qasim-i Anvar:

They say that in the end of his days, Amir Sayyid Qasim lived a life of comfort and had become fat, ruddy, and fair. An elder [once] asked him: “what is the mark of a true lover?” The sayyid replied, “decrepitude and sallow skin.” The man said, “but you look much different than this!” He replied, “Brother, there was a time when I was a lover, but now I am a beloved.” Then he recited the following verse from the Masnavi:

While a beggar, I lived in that pit of a house.

Then I became a king, and every king has to have a palace.9

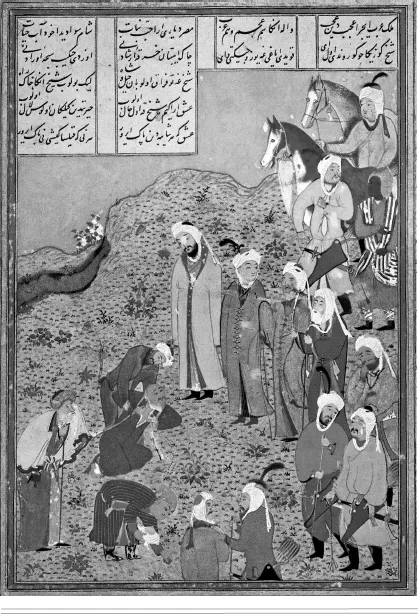

4.2 Shaykh ʿIraqi bidding farewell to a beloved friend....