![]()

1

Dispelling the Moses Myth

MOST OF THE MANAGERS we meet harbor a deep, dark secret: They believe in their hearts that they are not creative. Picasso they know they are not. They also know that being seen as short on talent for invention in these days of innovation mania is almost as bad as not knowing how to populate an Excel spreadsheet.

It all seems so unfair. After years spent focusing on prudence and proving the return on investment of any new idea, years spent trying not to look stupid, now all of a sudden we are also expected not to look—what would the word be—unimaginative? And each time some “creativity” consultant asks us to imagine ten novel uses for a paper clip, it confirms what we already know: We are no Steve Jobs, either. For most of us there will be no Moses-like parting of the waters of the status quo that we might safely cross the Red Sea of innovation. Drowning is more likely our fate.

But despite popular misconceptions, innate genius isn’t the only way to solve business problems creatively. Those of us who can’t part the waters need instead to build a bridge to take us from current reality to a new future. In other words, we must manufacture our own miracles. And a technology for better bridge building already exists, right under our noses. What to call it is a matter of some dispute, but for lack of a better term we’ll call it design thinking. Whatever label it goes by, it is an approach to problem solving that is distinguished by a few key attributes:

• It emphasizes the importance of discovery in advance of solution generation using market research approaches that are empathetic and user driven.

• It expands the boundaries of both our problem definitions and our solutions.

• It is enthusiastic about engaging partners in co-creation.

• It is committed to conducting real-world experiments rather than just running analyses using historical data.

And it works. Design thinking may look more pedestrian than miraculous, but it is capable of reliably producing new and better ways of creatively solving a host of organizational problems. Best of all, we believe that it is teachable to managers and scalable throughout an organization.

Despite some confusion over what to call it—the term design thinking sounds fuzzy to some people, and design is clearly about a lot more than thinking—prominent examples of companies applying the tools of design to improve business results come readily to mind in the wake of Apple’s success and IDEO’s visibility, and many organizations now get the attraction of design thinking. Although some companies still appreciate design’s power only for developing new products and services, organizations interested in innovation increasingly recognize it as a way to create new business models and achieve organic growth. In fact, using design thinking to identify and execute on opportunities for growth was the focus of our previous work. Now we want to take our exploration of design’s potential a step further.

Our goal in this book is to push the visibility of design thinking in business and the social sector to new places and to demonstrate that design has an even broader role to play in achieving creative organizational and even civic outcomes. This book is built around ten vivid illustrations of organizations and their managers and design partners doing just that—using design thinking in ways that work. Each story showcases a particular new use of design thinking. And each provides palpable examples of how organizations and individuals can stretch their capabilities when they approach problems through the design thinking lens. Using the voices of the managers and designers involved, we illustrate the value of a design thinking approach in addressing organizational challenges as diverse as reenvisioning call centers, energizing meals on wheels for the elderly, revitalizing a city’s urban neighborhoods, and rethinking strategic planning.

Our ambitions here are grand: to offer a blueprint for deploying design thinking across levels and functions in order to embed a more creative approach to problem solving as a strategic capability in organizations.

Building Bridges with Design Thinking

Design thinking offers a great start to bridge building. It fosters creative problem solving by bringing a systematic end-to-end process to the challenge of innovation. A few years ago, Jeanne Liedtka and Tim Ogilvie, the CEO of the innovation strategy consultancy Peer Insight, wrote a book called Designing for Growth (D4G, in our parlance), in which they laid out a simple process and tool kit for managers interested in learning how to use design thinking to accelerate the organic growth of their businesses. Here we aim to build on that work by examining how design thinking can be used to solve a broad array of other organizational problems, outside of growth. Whether your focus is producing growth, redesigning internal processes, engaging your sales force, or a host of other issues, the basic innovation methodology behind design thinking remains the same. Let’s first summarize the D4G approach:

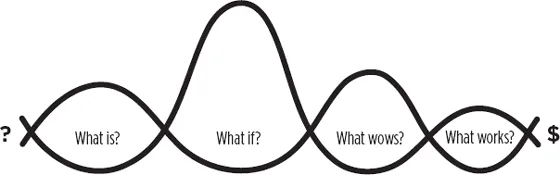

The process examines four basic questions, which correspond to the four stages of design thinking:

1. What is?

2. What if?

3. What wows?

4. What works?

What is? explores current reality. What if? uses what we learn to envision multiple options for creating a new future. What wows? makes some choices about where to focus first. What works? takes us into the real world to interact with actual users through small experiments. The widening and narrowing of the bands around each question represent what designers call “divergent” and “convergent” thinking. In the early parts of the process, and even within each stage, we are diverging: progressively expanding our field of vision, looking as broadly and expansively around us as possible in order to escape the trap of our mental models. We then begin to converge, gradually narrowing our options to the most promising ones.

Let’s look at each question in a bit more depth:

QUESTION 1: WHAT IS?

All successful innovation begins with an accurate assessment of what is going on today. Indeed, starting out by developing a better understanding of current reality is a hallmark of design thinking and the core of design’s data-intensive and user-driven approach. Managers frequently want to run immediately to the future, to start the innovation process by brainstorming new options and ideas, but attending to the present pays dividends in two crucial ways. First, it helps broaden and perhaps reframe our definition of the problem or opportunity we want to tackle. A lot of managers throw away all kinds of opportunities before they even get started by framing the problem too narrowly. Second, this attention to the present helps uncover unarticulated needs, which are key to producing the kind of innovative design criteria that generate valuable solutions. What is? saves us from having to rely entirely on our imaginations as we move into idea development and gives us solid and, ideally, deep insights into what our stakeholders truly want and need, reducing the risk that our new idea will fail. It specifies what a great solution will look like without telling us the solution itself.

QUESTION 2: WHAT IF?

Having examined the data we gathered, identified patterns and insights, and translated these into specific design criteria, it is time to move from the data-based exploratory What is? to the more creativity-focused What if? Again, rather than rely on our imaginations in the idea generation process, we use a series of trigger questions that help us think outside our own boxes. Next, we take these ideas and treat them explicitly as hypotheses (in the form of concepts) and begin to think systematically about evaluating them against our design criteria.

QUESTION 3: WHAT WOWS?

If we get the first two stages approximately right, we will find—to our simultaneous pleasure and dismay—that we have far too many interesting concepts to move forward all at once, and so we must make some hard decisions. As we winnow the field of concepts to a manageable number, we are looking for those that hit the sweet spot where the chance of a significant upside for our stakeholders matches our organizational resources and capabilities and our ability to sustainably deliver the new offering. This is the “wow zone.” Making this assessment involves surfacing and testing the assumptions underlying our hypotheses. The concepts that pass this first test are good candidates for turning into experiments to be conducted with actual users. In order to do this we need to transform the concepts into something a potential customer can interact with: a prototype.

QUESTION 4: WHAT WORKS?

Finally, we are ready to learn from the real world by trying out a low-fidelity prototype with actual users. If they like it and give us useful feedback, we refine the prototype and test it with yet more users, iterating in this way until we feel confident about the value of our new idea and are ready to scale it. As we move through this process, we keep in mind some of the principles of this learning-in-action stage: work in fast feedback cycles, minimize the cost of conducting experiments, fail early to succeed sooner, and test for key trade-offs and assumptions early on.

We will see these four questions at work in each of the ten stories we are about to share. Sometimes the entire process plays out. At other times, only pieces of it are evident. One of the most valuable aspects of design thinking is that you don’t need to follow every step soup to nuts. You can begin with any piece of it or with some of the tools. But process alone won’t be enough to build a bridge from current reality to a new future. You also need some tools to accompany the steps. In Designing for Growth Jeanne and Tim laid out a set of ten tools. In this book we consider several more. Although all of them are useful, and most will appear frequently in our stories, different tools are used for different purposes.

| 1 | Visualization

using imagery to envision possibilities and bring them to life |

| 2 | Journey Mapping

assessing the existing experience through the customer’s eyes |

| 3 | Value Chain Analysis

assessing the current value chain that supports the customer’s journey |

| 4 | Mind Mapping

generating insights from exploration activities and using those to create design criteria |

| 5 | Brainstorming

generating new possibilities and new alternative business models |

| 6 | Concept Development

assembling innovative elements into a coherent alternative solution that can be explored and evaluated |

| 7 | Assumption Testing

isolating and testing the key assumptions that will drive the success or failure of a concept |

| 8 | Rapid Prototyping

expressing a new concept in a tangible form for exploration, testing, and refinement |

| 9 | Customer Co-Creation

enrolling customers to participate in creating the solution that best meets their needs |

| 10 | Learning Launch

creating an affordable experiment that lets customers experience the new solution over an extended period of time, to test key assumptions with market data |

Some tools, such as journey mapping, use ethnographic methods such as interviewing and observation to help us escape our mental models by immersing us in the lives (and giving us access to the mental models) of stakeholders, whether they are customers, partners, internal clients, or citizens. These tools let us get at the unarticulated needs of these people and, in the process, build a human connection that helps us see the possibility of making someone’s life better. They are the very core of the What is? stage and are the foundation for generating value through the design thinking process. In general, your ultimate solutions will only be as good as your learning during this discovery phase.

Mind mapping is a clustering tool that helps us make sense of the torrent of data that comes at us at various points in the design thinking process. It can involve turning raw data gathered through ethnography into deep insights or sorting through the individual ideas we created during brainstorming to find those that can become concepts. This tool keeps us purposeful rather than overwhelmed.

Brainstorming and concept development, two tools used in the What if? stage, work with rather than against our natural tendencies. Instead of asking us to come up with ideas based purely on our imaginations, they provide structure and allow us to leverage the insights generated during the What is? stage. They let us play with new ideas without risking a lot and invite various stakeholders into the problem-solving process: employees who eventually must make the new concepts work, customers who must buy them, or partners who need to work together in order to deliver them. This is the collaborative heart of design.

Prototyping can be used at various stages of the process: to map What is? or to visualize What if? It expresses our ideas in tangible form and makes them feel real. Prototyping plays a central role in all ten stories. Our focus will be on what experts call “low-fidelity” prototypes, which are much simpler and less finished than what the word prototype conjures up for most managers.

Learning launches help us plan and conduct the small market experiments that are so critical to the learning by doing that underlies design thinking.

Taken together, the design thinking process and tools let us envision and build better solutions. But to do this we have to move beyond thinking of creativity and design as a...