![]()

1

PIRACY AND THE BIRTH OF FILM

WRITING IN 1926, film historian Terry Ramsaye described the first decades of the U.S. film industry as a “lawless frontier.” He dismissed the many piracy battles that consumed the first filmmakers, claiming that “ethics seldom transplant. They must be raised from seed, in each new field.”1 Ramsaye’s conclusion may have been right—new media require new ethics—but he overlooked the process through which media ethics are updated and rethought when he swept piracy battles under the carpet. It is in the debates over piracy that we see new media breaking away from the old. Piracy wars veil contests to control innovation and new avenues for creativity. Where we encounter piracy claims in new media, we find incumbent businesses trying to protect their investment in older media by resisting the new. On the other side, today’s pirates are often tomorrow’s moguls, who are simply pushing the limits of new technology in directions that have yet to be assimilated (or condemned) by the law or society. To be sure, many pirates simply take advantage of the temporary lawless frontiers that accompany the diffusion of new media. Whatever their motivation, most early filmmakers were pirates of one stripe or another.

Copyright law is the battlefield on which media piracy battles are fought; it is the official engine for distinguishing piracy (or, more innocuously, “infringement”) from the many legal forms of copying, distributing, performing, and building on art and culture. Judge Joseph Story (later a Supreme Court Justice) famously referred to copyright as the “metaphysics of the law.” We could add that copyright law is also the metaphysics of new media.2 Through copyright law, courts and Congress decide when existing laws are sufficient to regulate the aesthetic and commercial upheavals brought by technology and when new laws are needed to meet the novel demands of new technology.

Throughout the history of copyright and new media, the law has regularly domesticated new forms of copying and distribution. Radio, the VCR, cable television, and other new media all grew out of forms of communication that moved from the unstable category of piracy to a legal and socially acceptable status.3 But the early history of film in the United States is different. It is the story of a business built on two forms of copying that we would now consider piracy: selling exact copies of competitors’ films as if they were your own (a process known as duping) and making unauthorized adaptations of novels and plays. Unlike the law’s assimilation of the forms of piracy enabled by so many other media, both of these forms of copying were eventually declared illegal in landmark court cases, one in 1903 and one in 1911. This chapter examines those two cases and how they gave birth—for better or worse—to the American film industry.

The history of the emergence of film does not, however, suggest that piracy can be or should be stopped, even if that were possible. As we will see, piracy is a natural part of the development of new media. The metaphysical questions that legislators and judges struggled with were not how to stop piracy. Rather, they struggled with the question of whether film was a new medium that required new regulation or whether it was simply the extension of existing media. In both of the cases that determined how film would be regulated by copyright law, courts decided that film should be considered an extension of earlier media. Film was simply moving photography and virtual theater. I argue that both cases led to the further monopolization and vertical integration of the American film industry. Declaring film to be a new medium and drafting new legislation might have better served the art of film by developing a richer and more competitive market for film production, rather than the vertically integrated oligopoly that developed.

PHOTOGRAPHY: AN UNSTABLE BASE

What are movies? Just a lot of photographs strung together, right? That is what Thomas Edison’s lawyers argued at first. And the story of copyright law’s impact on the development of the U.S. film industry begins with Edison’s successful, though short-lived, attempt to monopolize the film business. The Edison Manufacturing Company and later Edison’s trust, the Motion Picture Patents Company, were involved in every landmark copyright case leading up to the 1912 Townsend Amendment, which officially added motion pictures to the Copyright Act.4 Edison and his confederates were slow to realize the centrality of copyright law to their endeavors, and, as we will see, they generally clung to old laws when new ones might have been more beneficial to their business. Until 1903, for example, the Edison Company campaigned to have films defined and protected as photographs. As a result of Edison’s successful campaign, the law defined films as photographs from 1903 to 1911—some of the most important years for the development of film style and the film industry.

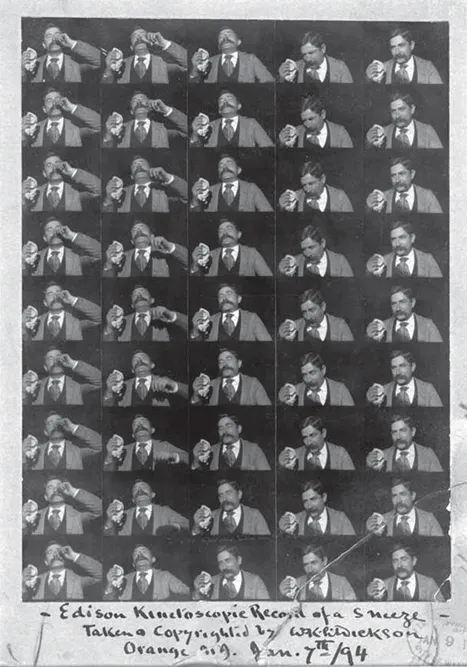

The Edison Manufacturing Company began registering its films for copyright protection as photographs in 1894. While looking for an illustration of its new motion picture technology for a promotional article in Harper’s Weekly, the Edison Company printed the entire film of laboratory assistant Fred Ott’s sneeze on a single sheet of paper (fig. 1.1). It then must have occurred to someone in the company that they had transformed their film into an object that could be protected by copyright law: a photograph. In accordance with the current copyright regulations, the Edison Company proceeded to register the photograph, pay the registration fee, and deposit two copies with the Copyright Office of the Library of Congress.

Over the next eighteen years (until 1912), Edison and his competitors experimented with different methods of copyright deposit. It is often thought that early film companies only deposited films printed on long strips of photographic paper known as “paper prints,” but occasionally they also deposited complete celluloid film negatives and positives; in some cases, they even tried depositing representative frames from every scene of a film. Several major film companies of the time, including the dominant French company Pathé Frères, went for long stretches without registering any films with the Copyright Office. The changing methods of applying (or not applying) for copyright reflected the battles to define what film is, to define standards of originality in filmmaking, and to stem the tides of piracy.

From the perspective of copyright history, one of the most fascinating things about the filing of paper prints is that this widespread practice went unchallenged and unverified for almost a decade. The practice of registering films as photographs is particularly troubling, because the status of photographic copyright was itself far from settled in the 1890s.

FIGURE 1.1 Edison’s Kinetographic Record of a Sneeze, aka Fred Ott’s Sneeze (1894), the first film registered for copyright. It was registered as a photograph.

Congress added photographs to the copyright statute as early as 1865 to accommodate the growing market for artistic photographs established by Matthew Brady and other photographers. Brady’s Civil War photographs, which were exhibited in New York galleries, helped to legitimize the medium, conveying aesthetic value and historical significance.5 England had also added photography to its copyright laws just three years earlier, and U.S. copyright laws frequently follow on the heels of British law, even today.6 The amendment to the Copyright Act, however, did not satisfactorily draw a line between photographs eligible for copyright registration and those that fell outside of the copyright system. Which photographs, for instance, were truly original and therefore deserving of copyright protection and which did not have enough of a spark of originality to fall under the copyright umbrella?7 Copyright, after all, protects originality, not artistic or historical significance. In determining whether photographers could be considered authors for merely pushing a button, copyright law came up against a strong and very long tradition in the theory of photography, articulated most famously by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. in the 1850s. This line of accepted wisdom held that the genius of photography—Holmes called it “sun-painting”—is precisely its ability to capture unbiased reality free of human mediation.8

A second line that remained to be drawn would separate photographs that could be considered original expressions from those photographs that belonged so firmly to the field of commerce that they forfeited copyright protection. In the 1879 Trade-Mark Cases, the Supreme Court made clear that the commercial purpose of many symbols and signs used for advertising disqualified them from the scope of copyright. And the ability of courts to see art in commerce has been a very gradual process. In the late nineteenth century, it was not at all clear where the line should be drawn for mass-reproduced postcards or other commercial photographs.9

As a result of these unanswered questions, photographic piracy remained rampant in the decades after the 1865 addition of photography to the Copyright Act. In the early 1880s, two cases directly questioned the constitutionality of adding photographs to the statute. In both cases the defendants claimed that they could not be considered pirates, because photographs were neither writings nor works of authorship, two constitutional criteria for copyright protection.10 The Supreme Court eventually heard both cases.

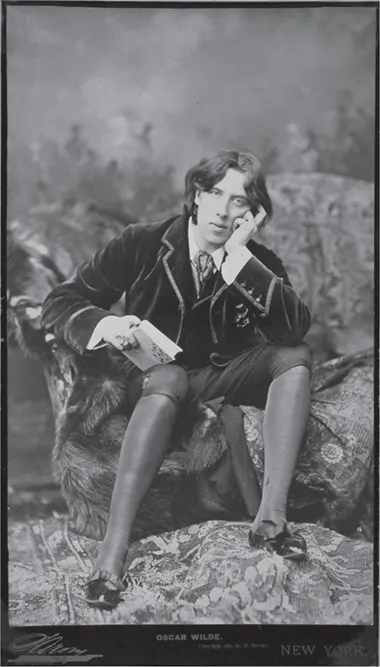

In the first and now very famous case, a well-known portrait photographer, Napoleon Sarony, sued the Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company for duplicating and selling copies of his portrait of Oscar Wilde (fig. 1.2). Sarony had built a successful business making cartes-de-visite, small photographic portraits that celebrities frequently distributed to enhance their fame. Oscar Wilde had yet to publish any of the works that made him an internationally known literary star, and he used the cards from Sarony to boost his profile on his first trip to America. A retail store in New York City, Ehrlich Brothers, decided to take advantage of the sartorial trends Wilde was bringing to America, and the store commissioned the Burrow-Giles company to print an advertisement for hats using the Wilde photograph (although, strangely, Wilde was not wearing a hat in the image in question). Over 85,000 copies of the ad were made by the time Sarony brought the printers to court in the case of Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony, 1884. The number of copies helps to indicate the scope of piracy at the time, almost twenty years after Congress had added photographs to the list of media covered by copyright law. When the Supreme Court decided the case, moreover, they did not exactly settle either of the burning questions. Did pushing a button constitute authorship? Did the commerce in photographic portraits negate their inclusion in the scope of copyright law?11

FIGURE 1.2 Napolean Sarony’s photograph of Oscar Wilde, the subject of the Supreme Court case Burrow-Giles Lithographic Co. v. Sarony (1884). Can a photographer be an author?

The Court did not doubt that images could be protected as writings, since the original U.S. Copyright Act of 1790 included maps and charts. But was a photograph different? Was it “simply the manual operation … of transferring to the plate the visible representation of some existing object, the accuracy of this representation being its highest merit?” The Court found that “this may be true in regard to the ordinary photograph, and, further that in such case a copyright is no protection. On the question as thus stated we decide nothing.” In other words, they sidestepped the pushing-a-button-as-authorship question entirely. The justices refused to rule on whether pushing a button constituted authorship, because they found another method for defining Sarony as an author. Sarony had posed Wilde, arranged his costume and the decor, and generally composed the image before the camera passively recorded it. As such, the photograph could be protected as the record of the arrangement of a creative scene. But this standard was very far from acknowledging that photographers were artists, whose creations were original works of art.12

Four years after the Sarony case, the Supreme Court decided a similar case, Thornton v. Schreiber, which had originally been launched two years before Sarony’s. The inconvenient death of one of the defendants and some confusion about whom to prosecute delayed the case’s route to the Supreme Court. In this case, Schreiber and Sons, a publisher of postcards and stereopticon views, sued Edward B. Thornton, an employee of the Charles Sharpless and Sons dry-goods company in Philadelphia. Without permission, Thornton had duplicated and published 15,000 copies of Schreiber and Sons’ photograph “The Mother Elephant ‘Hebe’ and her Baby ‘Americus,’” using the elephant photograph on packing labels for Sharpless’s merchandise (fig. 1.3).13

The Thornton case was very similar to the Sarony case. But this time, the court’s decision focused largely on how to award damages properly. At the opening of the case, Justice Miller, who had written both the Trade-Mark and the Sarony decisions, seemed simply to assume that the photograph of the two elephants was eligible for copyright protection with no further scrutiny. But had the photographer posed the elephants? Was the photograph, which was made by a company that specialized in commercial postcards and stereopticon views and used by the infringers in the production of labels, worthy of copyright protection despite its commercial nature? Had something changed between the two cases that suddenly expanded the law to include even advertising photographs? The Supreme Court did not signal a clear method of interpreting the copyright status of photographs, and confusion continued to reign.

An article in the New York Sun that was reprinted in Sci...