eBook - ePub

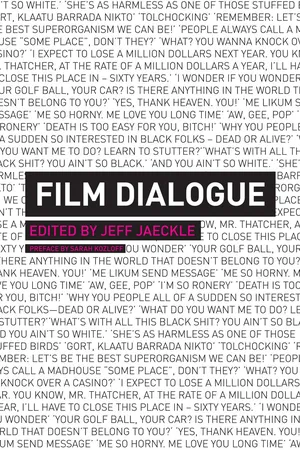

Film Dialogue

About this book

Film Dialogue is the first anthology in film studies devoted to the topic of language in cinema, bringing together leading and emerging scholars to discuss the aesthetic, narrative, and ideological dimensions of film speech that have largely gone unappreciated and unheard. Consisting of thirteen essays divided into three sections: genre, auteur theory, and cultural representation, Film Dialogue revisits and reconfigures several of the most established topics in film studies in an effort to persuade readers that "spectators" are more accurately described as "audiences," that the gaze has its equal in eavesdropping, and that images are best understood and appreciated through their interactions with words. Including an introduction that outlines a methodology of film dialogue study and adopting an accessible prose style throughout, Film Dialogue is a welcome addition to ongoing debates about the place, value, and purpose of language in cinema.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Film Dialogue by Jeff Jaeckle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Películas y vídeos. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

DIALOGUE AND GENRE

01

THE LEADEN ECHO AND THE GOLDEN ECHO: DIALOGUE IN SCIENCE FICTION FILMS

I remember once hearing an apocryphal story about a man, unfamiliar with English, who thought that the most beautiful, musical, romantic and mysterious word in the entire language was ‘cellador’. He had slurred together two extremely ordinary and less than beautiful words – ‘cellar’ and ‘door’ – to come up with something which sounded rather like the name of a magical Arthurian isle or the heroine of an Edgar Allan Poe poem. I have always hoped that the gentleman in the story never did learn sufficient English to suffer the literal disenchantment which comprehension would have caused.

In science fiction (SF) cinema, perhaps the quintessential equivalent to ‘cellador’ can be heard in The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951). It is a single magical line of dialogue spoken by Helen Benson (Patricia Neal) to a giant faceless robot: ‘Gort, Klaatu barrada nikto.’1 This sentence, through its internal rhythmic and grammatical structure, creates not only music but also an extraordinarily imaginative resonance. The meaning of the words and their order achieve a most delicate balance between sense and nonsense, between logical communication and magical litany.

In the film’s context, we understand the line generally but cannot grasp it precisely. Gort is the name of the robot, Klaatu the name of the alien visitor to Earth who has been shot and has instructed the woman to say the words to the robot, should anything happen to him. We may understand that the sentence is a command and in some way is meant to deter the robot from retaliation for Klaatu’s death. It may also suggest some course of action to the robot, for Gort is later seen mechanically ‘resurrecting’ Klaatu, whose body he has recovered. But what ‘barrada’ and ‘nicto’ actually mean, what parts of speech they are, remains a mystery. Is ‘barrada’ a verb perhaps, ‘nicto’ a negative, a noun? ‘Gort, Klaatu barrada nicto’ – one line of dialogue in a film otherwise emphatically comprehensible. Although there are a few other instances of alien language in the film, it is this particular line which lingers. The words themselves are wondrous for they let us speculate endlessly, they resonate. And – unlike other such dialogue – these words are spoken to an alien by a human. That linguistic reaching out takes us, even if only briefly, beyond the literal and limited boundaries of Earth and Earth-bound language. It is our ‘cellador’.

In all American SF cinema, only one film has seriously attempted to give us a spoken, and more importantly, a sustained language equivalent to its wondrous visual images – and is it certainly not coincidental that the film and the languages were adapted from a novel, A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess. In his 1971 film adaptation, Stanley Kubrick has retained and made sound from the rhythms of Burgess’ invented language, Nadsat. Spoken by protagonist Alex (Malcom McDowell) and his droogs (friends), the mixture of Anglicised Russian with comprehensible English is onomatopoeic, rich and lush, coarse, Elizabethan and definitely wondrous. Nadsat infuses the film with strangeness and tension, complementing or contrasting the images we see on the screen, the colourless speech of the other characters and the music on the soundtrack. Nadsat, particularly as spoken by Alex in a manner which Pauline Kael pejoratively dismisses as ‘arch’ (1974: 474), is more than a futuristic tongue, a sign of linguistic change, a gimmick; it is a song and an attitude, a celebration of sound itself and a new way of looking at, describing, and thinking about what our own eyes perceive in everyday contemporary English. We deal with Nadsat not only as an alien language, but also as the expression of a foreign mind – therein lies the wonder. Ironically, but understandably, Anthony Burgess – with due respect to A Clockwork Orange as a film – has written about the adaptation: ‘The light and shade and downright darkness of my language cannot, however brilliant the director, find a cinematic analogue’ (1975: 15). What is ironic is that Burgess has chosen visual terms to describe the written language of his book – and equally ironic is the fact that the success of that language in the film is in its sound, its being spoken aloud by a human voice which can indeed lighten it, shade it, darken it with menace. What is significant about the language of the film A Clockwork Orange has little to do with its literary qualities or the fact that it is adapted from written literature. Rather, the significance and impact of Nadsat in the film arises from the fact that is not read but spoken and heard as a truly wondrous, part-human, part-alien tongue. Making up one’s ‘rassoodock’, ‘tolchocking’ victims, ‘peeting vino’, using one’s ‘glazzies’, seeing things as ‘horrowshow’ or ‘ultraviolent’, recognising ‘gorgeosity’ – this is not literature in its film state (nor less than literature either, as Burgess would try to convince us) but spoken, expressive and living language. Its spoken combination of unfamiliar nouns, verbs and adjectives, common English, and poetic, surprising and punning portmanteau words is vital to the film’s creation of an alien consciousness and sensibility. In its achievement of this creation through spoken language, A Clockwork Orange is unique in SF cinema. As Philip Strick observes of the film, ‘it is the first sustained success on film of what science fiction writers … have long used as a necessary element in describing plausible futures’ (1972: 45).

‘Gort, Klaatu barrada nicto’ is an isolated line of wonder in an otherwise primarily dull, if intelligent, linguistic context; its imaginative resonance is, indeed, enhanced by its relative isolation. Nadsat, on the other hand, is an alien language which we as viewers and listeners learn as it is sustained for the film’s duration and parsed by linguistic and visual context. Both these films are successful in moving language beyond the feeble futuristic gadget-naming of most SF films (for example, the ‘Interociter’ of This Island Earth [1955]; or the ‘quanto-gravitectic hyperdrive and postonic transfiguration’ of Forbidden Plant [1956]). Unfortunately, however, both The Day the Earth Stood Still and A Clockwork Orange – in their attempts to create alien dialogue that is alien – are exceptions to, rather than, the rule. They are only two films in more than two decades of SF films that are not recognised by even the most ardent SF buffs for their adventurous treatment of alien or, for that matter, human dialogue.

Surely, one of the most disappointing elements of SF cinema is dialogue. How can a genre which so painstakingly tries to awe and surprise us with imaginative visuals seem so ignorant and careless of the stuffiness, banality, pomposity, dullness and predictability of its language? This lack of imaginative dialogue in the SF film has been consistently noted by film critics with either affectionate condescension or hostile interest since the genre arose in full force in 1950s America. Penelope Houston, in one of the earliest articles identifying and describing the genre, wrote: ‘One does not mind if space travel oversteps the bounds of the scientifically likely, provided that it does so with imagination. But Hollywood is perhaps not the starting point for such journeys. The shiny, gadget-crammed rocket is dispatched into a universe that comes straight out of the comic strips, and the Brooklyn boy or chorus girl, greeting a new planet with a “Gee! We’re here!” scarcely seem fitted for the tradition of a Columbus’ (1953: 188). Susan Sontag in her essay ‘The Imagination of Disaster’ states: ‘The naïve level of the films neatly tempers the sense of otherness, of alien-ness, with the grossly familiar. In particular, the dialogue of most science fiction films, which is generally of a monumental but often touching banality, makes them wonderfully, unintentionally funny’ (1965: 42). And Brian Murphy, discussing monster movies of the 1950s, attempts to relate the weak dialogue to the decade in which the films were made and, as well, suggests the crux of the aesthetic problem posed by SF dialogue:

Prose itself became horrifying, and the response was, certainly not poetry but, more and more prose; and the more scientific, the more it sounded like computerised jargon, the better, the more reassuring. One cause of this general weakness of monster movies is the poverty of the language. Poverty of language turned the U.S. moon flights into bores because no one, except a few journalists, could think of any compelling way to talk about them. There is a similar aesthetic problem in monster movies: they deal with interesting problems and even Great Issues, but it is nearly impossible to remember anything that is said in them. (1972: 36–7)

Suggested here are two major reasons for the presence of weak dialogue in SF films. One is that it is almost a condition of the genre, part of the form itself. The banality, the laconic and inexpressive verbal shorthand and jargon, the scientific pomposity, are needed to counterbalance the fear (of both falling and flying) generated by the visual image which takes risks and is unsettling. How do we reconcile the visual sight of a rocket launch (all fire and thrust and movement) with the verbal reduction of that image to an ‘A-OK. We have lift off’? How do we reconcile the awesome visual poetry of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), for example, with its tedious half-hearted dialogue which barely approaches prose? Murphy would see this reductionism as necessary, as evidence that a terrifying (even if wondrous) world is under control, reduced through containing and controlling jargon to human size and manageable predicament. Sontag would see the juxtaposition of the grand image with small talk as an attempt to ‘normalize what is psychologically unbearable, thereby inuring us to it’ (1965: 42), a case of the word neutralising the image. Indeed, the idea that small talk and big images are necessary screenmates – are, in fact, a definitive element – of SF cinema is not at all untenable. The American SF film, no matter how abstract individual images may be, finally grounds itself in comprehensibility, in its necessary commerciality, and dialogue helps ground it. The jargon and banality Murphy identifies as a reassurance the 1950s viewer, in particular, needed and wanted perhaps can be more generally identified with the aesthetic tensions and essential contradiction of the genre. Therefore, the history of the SF film up to the present can lead one to expect that more often than not, the more wondrous and alien the image, the more usual and Earthly the spoken word.

The other suggested reason for the poverty of language in a great deal of SF cinema confronts a crucial artistic problem. How does one talk in a compelling way about things which are conceptually magnificent, visually exciting, but linguistically dull or difficult, abstract or reductive? How, for example, can an observation, explanation or description of the approaching roving star Bellus and its planet Zyra in When Worlds Collide (1951), match in any way its visualisation? The observation and description are only a pale approximation of the image, and an explanation removes the emotion contained in the magic of seeing what we see on the screen. The language of science, after all, is scientific – formulaic, abstract, abbreviated, jargon which is coolly functional and essential to quick and clear communication. It is also a language which strives towards the most objective unemotional communication possible and is therefore – in its straightforward manifestation – totally unimaginative.

Ironically, part of the problem at issue here can be dramatically illustrated by a brief interchange in Marooned (1969), a film which Pauline Kael appositely (though in terms of the genre, uncomprehendingly) described as having ‘a script that sounds as if the author had never met a human being’ (1974: 107). The implicit contradiction between the empirical scientific method and the human imagination occurs in a nonscientific conversation between the three astronauts trapped in ‘Ironman One’, a space capsule orbiting the moon. They are all exhausted, hopeless of rescue, and one of them, Buzz (Gene Hackman), nearly hysterical. The calmest and least emotional of the three is Stoney (James Franciscus) who, to pass the time and perhaps calm the other two men, remembers that all three had taken a psychological test in which they were shown a blank piece of paper and then asked what they saw. Stoney reminisces that he was the only one to answer, ‘A blank piece of paper’. ‘No imagination?’ one of the other trapped astronauts asks him. ‘No’, Stoney says. ‘Devotion to truth.’

Poetic imagination and scientific truth are verbal enemies in a great deal of SF films. One might suggest, however, that because of the average viewer’s inability to understand the technical language of science, like the man who found poetry in ‘cellar door’, he too will find beauty in the language’s mystery, poetry in its inaccessibility. But that seems not to happen in most cases in which the scientific jargon is presented straightforwardly. The language of science, designed to be exclusive rather than inclusive, eschews resonance. Poetry and mystery never have a chance against the reductive excess of competence, efficiency, assurance and flatness which sounds across the screen. Imaginative flights of rhetoric (if they appear at all in such SF films) tend to be regarded by both characters and viewers suspiciously as manifestations of fatigue and stress or, at worst, psychosis.

Another reason for the dull, unemotional-ergo-inhuman language in many SF films is that in laboratories, around space installations, in and about scientific haunts and allied institutions, there is, in fact, dull language. In a space station orbiting the Earth, an astronaut talks about ‘cleaning house’; in military discussions of human casualties, euphemisms like ‘hair mussing’ are used. Both are verbal evidence of an inadequate or inappropriate response to actual stimuli. The first instance would perhaps be a touching demonstration of inadequate response had it not been delivered with such cheery aplomb. The second instance is a sample of what Stanley Kubrick has called ‘statistical and linguistic inhumanity’ (Kubrick in Walker 1971: 185). But, however one interprets or feels about this kind of language which subdues experience, it is authentic – and it is authenticity toward which the SF film strives. This is not merely a case of pathetic fallacy. We cannot forget that while the science and/or technology and/or problem in all SF films may be credible, possible, or even probable, it is never actual. Therefore, dull and routine language by remaining dull and routine may very well authenticate the fictions in the films’ premises or images.

As of now, the dull and flat language of reality is often used to create credibility and lend a documentary quality to SF cinema. Thus, Neil Hurley, a theologian and film critic, is prompted to ask: ‘Is it possible that men will become more neuter and less human as they immerse themselves in technology?’ (1970: 164). And a Columbia University student can accurately say to Mademoiselle magazine, which featured an article on science fiction: ‘Staggering things are being done by boring, bland people. Who wants to talk to one of the astronauts? This is an age of exploration that beggars Drake, but there aren’t going to be any more gallant Lindberghs setting out alone’ (Cunningham 1973: 140). The language of science and technology is anti-romantic and thus anti-individualistic; it does not express personality and consequently it is anti-heroic. Who, indeed, wants to talk to one of the astronauts? The astronauts are a team hero, speak a team language which brooks no romantic self-consciousness. The astronauts exist plurally, not singly, outstandingly, as did Drake and Lindbergh. The dull language, the flat intonations of SF film are exceedingly democratic in their reductive capacity, their ability to efface personality. This resultant lack of differentiation destroys the dramatic concept of character and, as well, the traditional relationship between the screen hero a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Notes on Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction: A Brief Primer for Film Dialogue Study

- Dialogue and Genre

- Dialogue Auteurs

- Dialogue and Cultural Representation

- Index