![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

MIGRATION IS a form of dispersal involving regular movement and return between one place and another (Odum 1971:200; Fretwell 1972:130; Rappole 2005a), where “dispersal” is defined as a movement of an individual away from its place of birth or center of population density (Ricklefs 1973). For birds, the most typical form of migration involves an annually repeated, seasonal movement between the breeding range and those regions where breeding does not occur. The difference between migration for organisms in general and the phenomenon as it occurs in birds is principally a matter of scale in space and time. The purpose of this movement, regardless of the distances involved, is to exploit two or more environments whose relative suitability in terms of survival or reproduction changes over time, usually on a seasonal basis (Mayr and Meise 1930; Williams 1958; Rappole et al. 1983; Terrill 1991). A core concept for us is that the preponderance of field data that we will summarize in the course of this volume supports the view that initial movement by the first migrants (dispersers) was from a home environment of greater stability to one of lesser stability (i.e., greater seasonality); in other words, that most migrants derive from populations that evolved as breeding residents in their current wintering areas, not from populations originally resident on their current breeding areas.

DEVELOPMENT OF HUMAN UNDERSTANDING OF MIGRATION

Early human understanding of migration was based on extensive, but technically limited, observations subjected to limitless imagination. References to seasonal disappearance and reappearance of migrants, as well as to flocks of birds apparently in transit, is extensive in the classical literature—for example, the Bible, Pliny the Elder, and Aristotle—but most explanations were fanciful at best (Wetmore 1926; Hughes 2009). An exceptionally insightful work from the Middle Ages is the monograph De Arte Venandi cum Avibus, written by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1194–1250), in which the author discusses feeding habits, morphology, and flight patterns of migrant versus resident birds. Sir Francis Bacon’s publication of The New Organon in 1620 helped to establish a method for development and testing of hypotheses based on systematic accumulation of data, a concept that greatly enhanced investigation of natural phenomena, including migration. Ensuing developments are discussed in Birkhead’s (2008) history of ornithology, The Wisdom of Birds. Among the landmarks was Catesby’s (1746) presentation to the Royal Philosophical Society, which reflected some of this progress. Nevertheless, serious flaws in elementary comprehension remained (Catesby 1748). Even Linnaeus (1757) had some confused notions concerning migration, and as late as 1768, Samuel Johnson, as well educated and well read a person as existed at the time, could state with perfect confidence, “That woodcocks, (said he,) fly over the northern countries, is proved, because they have been observed at sea. Swallows certainly sleep all the winter. A number of them conglobulate together, by flying round and round, and then all in a heap throw themselves under water, and lye in the bed of a river” (Boswell 1791). In central Europe, bird fanciers noted behavioral changes in captive migrants that gave rise to ideas of “inborn migratory urge,” with the first published description of migratory restlessness (Zugunruhe) appearing in 1707, and more thorough analyses of migratory activity in captive birds published by Johann Andreas Naumann in the late eighteenth century (Birkhead 2008).

The number and sophistication of observers increased rapidly during the nineteenth century, accompanied by wide dissemination of the results of their investigations through presentations at scientific meetings and publication. By the early twentieth century, the broad outlines of the timing, species components, and routes for avian migration systems in North America, Europe, and parts of Asia were fairly well understood (Middendorf 1855; Palmén 1876; Menzbier 1886; Gätke 1891; Clarke 1912; Cooke 1915; Wetmore 1926). Nevertheless, even the outlines remain somewhat dim for a few of the world’s major migration systems—for example, the austral and intratropical migration systems of South America (Chesser 1994, 2005; Rappole and Schuchmann 2003) and the Himalayan–Southeast Asian systems (Rappole et al. 2011a). In addition, although the breadth and depth of scientific investigation of migration expands at a rapid pace in the early twenty-first century, significant questions remain, and new questions continue to appear (Bowlin et al. 2010).

ORIGINS OF MIGRATION

In the context of an evolutionary perspective of migration, consideration of the origins of migration are necessary. This topic has seen much debate (Zink 2002; Rappole et al. 2003a; Louchart 2008). For constructive discussion in the context of our analysis, we suggest that it is helpful to distinguish four meanings for the concept “origin of migration”:

• The deep history of migration (i.e., its initial advent in geologic time in any organism)

• Its first occurrence in class Aves

• Its first appearance in a given avian taxon

• Its most recent occurrence in a given population or fraction of a population

In the first sense, migration likely appeared very early in the history of the development of life on Earth, which is why it has been found in such a wide range of organisms, including plankton, cnidarians, copepods, crustaceans, insects, fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals (Baker 1978; Ohman et al. 1983; Neill 1990; Dingle 1996; Bowlin et al. 2010). With regard to its first occurrence in class Aves (second sense of the meaning “origin of migration”), the earliest origins likely date back to the first evolutionary appearance of the group, with regular, large-scale movements probably being as old as flight and seasonality (Moreau 1972:xi; Alerstam 1990:6). The importance of seasonal change in habitat caused by variation in temperature or precipitation as the principal engine driving the development of long-distance migration is that such change provides powerful selection forces favoring those individuals capable of exploiting seasonal environments (Rappole and Tipton 1992; Rappole et al. 2003a; Rappole 2005a). Semiannual changes of habitat quality through effects on temperature or precipitation, the presumed environment favoring development of long-distance avian migration, is probably almost as old as terrestrial vegetation for a significant proportion of the planet’s land surface. Seasonal habitats (e.g., deciduous forest) vary a great deal over the course of geologic time in their percentage of land cover and their location (Louchart 2008) according to whether or not an Ice Age is under way, but they have been a part of Earth’s ecology since at least the Eocene Epoch of the early Tertiary, which predates the appearance of most modern bird families in the fossil record (Brodkorb 1971; Ericson et al. 2006; Chiappe 2007).

Holarctic environments during the Tertiary were, in general, much warmer than they are today, with subtropical climate at times extending as far as 50°N latitude (Louchart 2008; Finlayson 2011:15). Fossils dating from the Eocene (54–38 mya) and Oligocene (38–24 mya) of species representing avian families or their ancestors that are now considered tropical or subtropical (e.g., potoos [Nyctibiidae], trogons [Trogonidae], colies [Coliidae], and parrots [Psittacidae]) have been discovered in northern Europe (Mayr and Daniels 1998; Mayr 1999, 2001; Dyke and Waterhouse 2001; Kristoffersen 2002). Unfortunately, it is not possible based on their remains alone to tell whether or not these birds represented seasonal migrants on their summer breeding grounds or subtropical residents. There are modern examples of species of parrots and trogons known to migrate between temperate or subtropical portions of their breeding quarters and tropical or subtropical wintering quarters (e.g., Red-headed Trogon [Harpactes erythrocephalus], Elegant Trogon [Trogon elegans], and Burrowing Parrot [Cyanoliseus patagonus]) (Chesser 1994; Kunzman et al. 1998; Rasmussen and Anderton 2005a), which at least supports the possibility that these species could have been summer residents in the northern Holarctic during the Eocene and Oligocene, but there is no way of knowing for certain. Even if ancient DNA could be recovered, it is unlikely that a migrant individual could be clearly distinguished from a resident (Rappole et al. 2003a; Piersma et al. 2005a; Finlayson 2011:16), although some aspects of refinement for a migratory habit might be discernible from fossils (e.g., wing shape).

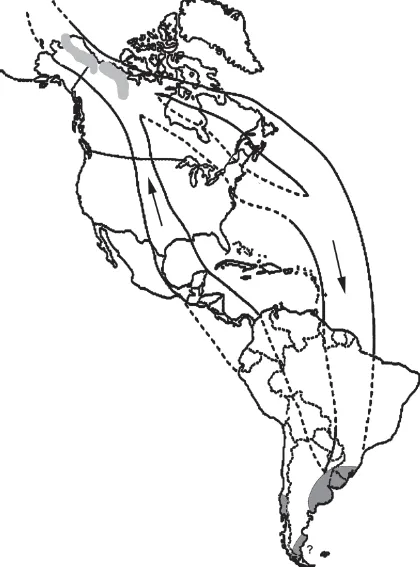

The third meaning for “origin” (development of migration in a particular avian taxon) is a much more recent event than either of the first two, at least for most species. Even so, the answer to the question of precisely how recently migration has appeared in any given taxon can be difficult to address. One reason for this difficulty is that resident species possess many if not most of the adaptations required of migrants, so that there are no known markers signaling a migratory habit whose appearance in a given phylogeny can be timed (Piersma et al. 2005a). Despite this qualification, it seems clear that for some groups or species, the origin of migration is much older than for others. For instance, a number of sandpiper species (Scolopacidae;—for example, the Eskimo Curlew Numenius borealis)—have breeding and wintering portions of the range separated by several thousand kilometers and lack conspecific populations that occur as year-round breeding residents in any portion of their current range (figure 1.1) (McNeil et al. 1994). Species of this sort evidently represent an evolutionary commitment to long-distance migration that is reflected not only in their lack of close relatives among resident populations in their home hemisphere but also in their wing structure (Pennycuick 1975) and transoceanic nocturnal navigation capabilities (Williams and Williams 1990). Nevertheless, it is important to remember that even for these species, many aspects of migration are fairly recent, as their current breeding areas were covered by several kilometers of ice up until a few thousand years ago (Finlayson and Carrión 2007).

An additional confounding factor for determination of time of origin of migration in a given species is that migration can appear or disappear in a population over very short time periods (Rappole et al. 1983; Able and Belthoff 1998; Helbig 2003; Rappole et al. 2003a; Pulido and Berthold 2003, 2010; Bearhop et al. 2005; Helm et al. 2005; Helm 2006; Helm and Gwinner 2006a; van Noordwijk et al. 2006). Hence, currently observed migratory behavior could have arisen from a fourth sense of the term “origin”—that is, as reinitiation of an activity that is well inside the evolved behavioral range (i.e., “reaction norm”) of a species or population. The continental changes in range and migration pattern over very short time periods demonstrate the extraordinary flexibility in this dispersal/migration system, even in one that is newly developed (for a discussion on the evolution of migration, see chapter 8).

FIGURE 1.1 Range of the Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis) in the mid-nineteenth century (Gill et al. 1998): light gray = breeding; dark gray = winter; arrows = migration route by season.

TYPES OF MIGRATION

There are no species of birds, even flightless ones, in which some part of the population does not undertake movement away from the breeding territory during some time of the year, whether through dispersal, extended foraging flights, or some sort of migration. In table 1.1, we list examples of major movement strategies of avian populations, placing the different types of migration into this continuum, which we discuss in the sections that follow. We emphasize that several of these strategies are not mutually exclusive; that the grouping is somewhat arbitrary; and that in many species, local populations may differ among each other in terms of their migratory behavior (Terrill and Able 1988; Nathan et al. 2008; Newton 2008). Nevertheless, definition and depiction of these migration types serves the purpose of placing long-established categorization usage into the context of our continuum view of migrant evolution.

TABLE 1.1 Major Movement Strategies of Bird Populations

| MOVEMENT TYPE | DESCRIPTION |

| Local seasonal movements | This movement type includes several different seasonal movements found in supposedly sedentary species (e.g., postbreeding dispersal, distance foraging, and single- and mixed-species flocking). |

| Facultative migration | Movement during the nonbreeding season depends on environmental effects (e.g., weather, social interactions, and variation in food supply). As a consequence, individuals of the population move variable distances from the breeding territory; includes irruptive migrants. |

| Partial migration | Population consists of a migrant and resident fraction; some individuals undertake regular migrations while others remain on the breeding gro... |