![]()

I

FROM

CATHEDRAL

TO IMAX

SCREEN

CASE STUDIES

IN IMMERSIVE

SPECTATORSHIP

![]()

1

IMMERSIVE VIEWING AND THE “REVERED GAZE”

THIS CHAPTER INVESTIGATES medieval Christian iconography as an instance of the “revered gaze,” a way of encountering and making sense of images intended to be spectacular in form and content and that heighten the religious experience for the onlooker. As the first chapter of a book about visual technologies that send shivers down the spine and that complicate our traditional understanding of film spectatorship, this interdisciplinary examination of the discursive origins of religious iconography may also suggest new ways of thinking about the nature of religious viewing across art history, cultural, and visual studies. By examining the architectonics of the cathedral and visual representations of Christ’s Passion, I hope to parse their unique signifying properties in order to produce a more historically sensitive account of how ideas of spectacle and immersion, defining features of contemporary amusements such as IMAX, theme park rides, and highly illusionist museum installations, long predate their incarnation in contemporary forms.

This chapter also builds upon the emergence of postmodern theory within medieval studies, a paradigmatic shift that finds traction in medieval theater scholar Pamela Sheingorn’s call for scholars to continually keep the Common Era in mind when conducting research, to excavate the “sedimentation of the Medieval” in contemporary discourse rather than simply view the Middle Ages as darkly “Other.”1 In response to medieval art historian Michael Camille’s criticisms of studies of the history of visuality for lumping together medieval ways of seeing into an “Edenic, free-floating era before the ‘Fall’ into the ‘real world’ of Renaissance perspectival vision,” this chapter acknowledges the “period eye” and its reverberations in contemporary religious epics such as Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004).2

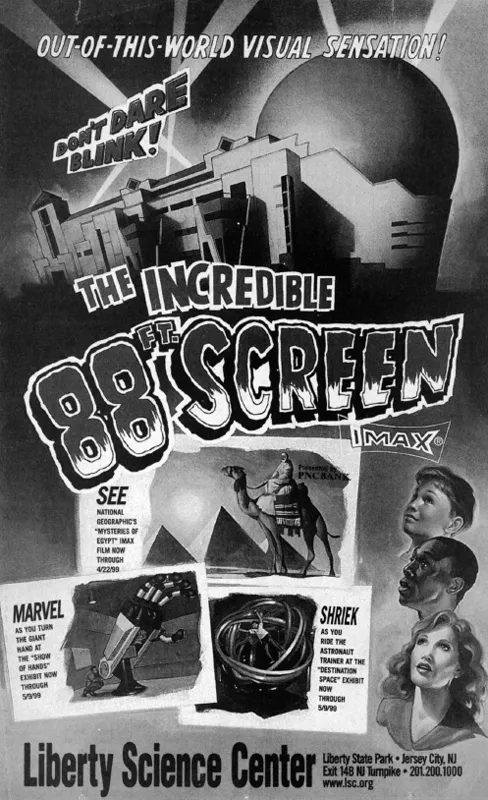

Although it may seem strange to begin a book about the immersive view and the nature of spectacular viewing with a discussion of medieval cathedrals, as the iconic sign of Christianity, the cathedral inscribes several themes taken up in this book, including spectatorship, immersion, the reenactment, virtual travel, visual excess, mimesis, the uncanny, and death. The first part of the chapter considers how the space of the cathedral is both pre- and overdetermined by wonder and awe (how, for example, such a stunning architectural feat was accomplished). In light of these factors, it would be remiss of me not to consider the cathedral as a hugely significant pre-cinematic site of immersive viewing experiences. I am interested in how the viewing coordinates privileged by the cathedral—the upward gaze, large number of spectacular art objects (especially stained glass), and sense of being in closer communion with a divine being—are vital elements in a revered gaze that is transhistorical and that has transmuted today into theme park rides, IMAX films (seen here in this poster for IMAX at the Liberty Science Center, in which the spectator is shown looking awestruck not directly out at the screen, but upwards, toward the top of the frame, a rapturous gaze) (fig. 1.1), and other jaw-dropping spectacular experiences such as the exhibits at Disney’s Epcot Center.

Fig 1.1 Poster for IMAX from Liberty Science Center (1999), showing the upward, “revered” gaze.

Some questions this chapter addresses include: Are-there ways of seeing that are determined by the period eye, or might more fluid models of visuality across time and place be imagined? What did pilgrims and other spectators hope to achieve by visiting cathedrals and religious shrines, and how did the spectacle they encountered when they arrived shore up their belief? Given that it is impossible, as art historian David Freedberg has argued, to know whether modern spectators responded in the same ways to religious artifacts (or their secular substitutes) as their thirteenth-century contemporaries, we can explore, in Freedberg’s words, “why images elicit, provoke, or arouse the responses they do … and why behavior that reveals itself in such apparently similar and recurrent ways is awakened by dead form.”3 If conjecture is the only tool available to the analyst of such historically distant and ephemeral practices of spectatorship, we can, as Michel de Certeau reminds us, “tentatively analyze the function of discourses which can throw light on [our] question” since these discourses, “written after or beside many others of the same order” speak both “of history” while inescapably “already situated in history.”4

The second half of the chapter examines the representation of religious iconography as a form of spectacle that is both performative and immersive. From the Latin spectaculum (or spectare, meaning “to watch”), “spectacle” in Webster’s dictionary is defined as “something exhibited to view as unusual, notable, or entertaining,” although its use to define an object or person as a thing of curiosity or contempt is equally important.5 While my use of the term spectacle incorporates both standard and pejorative connotations, I argue that when used in the context of religion, spectacle threatens to disrupt traditional object/viewer relations, asking something different of us as viewers and requiring new models of spectatorship. This contradicts cultural theorist Susan Stewart’s claim that the viewer of spectacle is “absolutely aware of the distance between self and spectacle”; on the contrary, religious-based spectacle, while sharing some of the same qualities as the model of spectacle outlined by Stewart, requires a form of identification that is mostly absent in the three-ring-circus spectacle commonly associated with the term.6 Not only does religious spectacle invite identification for some (clearly not all) spectators, but it also does so via a performative mode of address inscribed in the Passion narrative, whether in the form of the Stations of the Cross or in the imitatio Christi.

The spectacular “effects” of the Crucifixion (and Christian iconology in general) will also be considered in relation to the idea of God as an absent presence and the phantasmagorical aspects of religious witnessing. Some preliminary disclaimers are in order. In making these arguments, I am neither implying an ancestral link between churches and modes of spectatorship found in panoramas, planetariums, cinemas, and museums nor attempting to construct a social history of religious spectatorship. Despite the fact that the architectonics of the cathedral, the panorama rotunda, planetarium, cinema auditorium, and museum gallery share something in common in several phenomenological aspects—one could argue that each constructs an experience for spectators premised upon a dialectic of belief versus disbelief and the notion of an absent presence—there is no teleological link between them. They are clearly historically unique ways of representing the world, with their own ontologies, signifying practices, and ideologies. Second, while this chapter is concerned exclusively with Christian iconography, I am not claiming that Christian image-making and its attendant ideologies are sui generis or superior examples of religiously derived discourses of spectacle, immersion, and interactivity.

OTHER-WORLDLY SPACES: CATHEDRAL ARCHITECTONICS, PILGRIMAGE, AND SPECTATORIAL BLISS

Gothic cathedrals were a response to the desire for a building design capable of evoking a religious experience, “the representation of supernatural reality,” or what art historian Otto von Simson calls an “ultimate reality.”7 And yet in sharp contrast to the other spectatorial sites examined in this book, “the tie that connects the great order of Gothic architecture with a transcendental truth is not that of optical illusion” (how can an architectural space be read as an “image” of Christ?) but rather Christian symbolism, or more accurately, the concept of analogy (the degree to which God can be discerned in an object).8 As an architectural “language,” the Gothic style developed local dialects, all of which strove to capture the ultimate reality of Christian faith, the “symbol of the kingdom of God on earth.”9 The Gothic style began to take root under the Abbot Suger in the Benedictine abbey church of St. Denis in the early twelfth century, spreading by the mid-twelfth century to the cathedrals of Noyon, Senlis, Laon, and Paris.10 Platonic ideas of order, mathematical precision, and cosmic beauty dominated, and the principles of arithmetic and geometry inscribed in the physical design of the cathedral invited medieval spectators to intuit the order of the cosmos.11 Von Simson’s examination of the experience inspired by the cathedral sanctuary is concerned less with what the Gothic cathedral stands for than how the cathedral represents the vision of heaven, how as “enraptured witnesses to a new way of seeing,” medieval worshippers would have experienced (in a religious and metaphysical sense) a divine presence as signified by the architecture, light, iconography, and the exterior and interior design of the building.12 The walls, windows, and soaring vaults of the cathedral were conceived as a new form of architectural space that would have a powerful impact on the spectator. Gothic art was, as Camille states, “a powerful sense-organ of perception, knowledge, and pleasure.”13 The transcendental truth that medieval worshippers sought from the architectural design of medieval cathedrals can thus be seen as a “mystical correspondence between visible structure and invisible reality.”14

With this in mind, it is easy to see how Gothic cathedrals were complex communicative structures, rising over the horizon like “three-dimensional sermons”;15 they were constructed as “advertisements in stone, heralding the promised glories of things to come.”16 The architectural design of these spaces bespoke a great deal about the nature of the immersive spectatorial experiences to be had within: spectacle and a heightened sense of immersion were not only expected but came to define the very nature of the overall religious experience; as Camille argues, “Medieval cathedrals, like computers, were constructed to contain all the information in the world for those who knew the codes. Medieval people loved to project themselves into their images just as we can enter our video and computer screen.”17 The cathedral edifice thus took on a symbolic and aesthetic significance that far exceeded the structural functionalism of earlier church design (God himself was somehow mysteriously present within its walls); the architect and builder were less significant than the effect created by their work, as von Simson argues: “The author of the sublime achievement of this kind, paradoxically enough, recedes behind his work; we are absorbed infinitely more with the objective reality to which this work bears witness than we are with the individual mind that created it. That precisely is the experience the medieval architect wanted to convey.”18 In the design of the Gothic cathedral, a religious vision was translated into an architectural style in which the builder superseded the painter as the creator of the “singular convergence of structural and aesthetic values achieved by the geometrical functionalism of the Gothic system.”19 This yoking of the material to the spiritual appealed to the medieval mind which sought “true knowledge” through the penetration of the outward form of things to the inner meaning God intended; in the words of French Gothic scholar Emile Mâle, “all being holds in its depths the reflection of the sacrifice of Christ, the image of the Church and of the virtues and vices.”20 This divine being was none other than God himself, who in David Morgan’s words, “greeted the devout in the icon.”21

Cathedrals were intrinsically multimedia, multisensory spaces (the apotheosis of the sensorially rich pilgrimage), if we can appropriate a twentieth-century concept to describe a thirteenth-century edifice. The mixed media forms on display in the cathedral were the collective effort of artisans and craftsmen, who, far from imposing a personal vision on their artistry, worked in unison to produce “an art of multi-media combinations, in which whole environments are constructed by teams of masons, sculptors, [and] painters.” Moreover, “Gothic artists disclosed a world of incredible intensity and color, constructing richly embellished three-dimensional objects into which people could enter psychologically.”22 The architecture and visual logic of the interior design formed the perfect backdrop for rituals involving the stimulation of aural, haptic, olfactory, and oral senses via the Mass and its attendant rituals. Spectators experienced their faith not only iconographically but corporeally, since attending the liturgy and receiving communion in a Catholic Mass was, and still is, an elaborately detailed theatrical performance (the priest is, after all, imitating Christ in the liturgy as an actor would); a simple upward gaze to the roof delivered visual pleasure as seen in this image of the brightly painted roof and flying buttresses of Exeter cathedral in England (fig. 1.2).

Churches in the Middle Ages were a riot of color radiating from the stained glass windows as well as other architectural features and art objects; at Exeter cathedral, for example, “tombs, bosses [decorated protrusions of wood or stone carved with foliage, heraldic, or other decorations], corbels, screens, the sedilia, the images of the west front, the minstrels gallery and other statuary, and to a certain extent, the walls themselves presented a rich tapestry of color and design.”23 The impact of these brightly colored images upon the medieval mind must have been considerable, with no real equivalents for the image-saturated twenty-first-century sensibility. But these spatial forms do more than provide surfaces for color; the pointed-arch and canopy, for example, provided “a locus, a place for viewing [that] functioned something like a frame in modern painting,” and light and luminous objects served a crucial role in evoking God’s mystical presence wi...