![]()

Part 1

Investment Philosophy

dp n="27" folio="6" ?dp n="28" folio="7" ?

INTRODUCTION

Out of the blue one day, I received a complimentary e-mail from a guy who had read one of my essays. I was appreciative but didn’t think much of it until I noticed he had found the piece on a Web site dedicated to traders. Given that my focus is almost exclusively on long-term investing, I found it odd that a trader would find use for these ideas.

So I looked to see what else was out there and found something that surprised me even more: one of the essays was highlighted on a gambling Web site. While I study and appreciate gambling methods, I felt—as most self-righteous investors do—that long-term investing is nearly the opposite of most forms of gambling. After thinking about it, though, I realized there is a tie that binds all of these worlds: investment philosophy.

Investment philosophy is important because it dictates how you should make decisions. A sloppy philosophy inevitably leads to poor long-term results. But even a good investment philosophy will not help you unless you combine it with discipline and patience. A quality investment philosophy is like a good diet: it only works if it is sensible over the long haul and you stick with it.

Investment philosophy is really about temperament, not raw intelligence. In fact, a proper temperament will beat a high IQ all day. Once you’ve established a solid philosophical foundation, the rest is learning, hard work, focus, patience, and experience.

Quality investment philosophies tend to have a number of common themes, which the essays in this part reveal. First, in any probabilistic field—investing, handicapping, or gambling—you’re better off focusing on the decision-making process than on the short-term outcome. This emphasis is much easier announced than achieved because outcomes are objective while processes are more subjective. But a quality process, which often includes a large dose of theory, is the surest path to long-term success.

That leads to the second theme, the importance of taking a long-term perspective. You simply cannot judge results in a probabilistic system over the short term because there is way too much randomness. This creates a problem, of course; by the time you can tell an investment process is poor, it is often too late to salvage decent results. So a good process has to rest on solid building blocks.

The final theme is the importance of internalizing a probabilistic approach. Psychology teaches us there are a lot of glitches in the probability module of our mental hardwiring. We see patterns where none exist. We fail to consider the range of possible outcomes. Our probability assessments shift based on how others present information to us. Proper investment philosophy helps patch up some of those glitches, improving the chances of long-term success.

A closing thought: The sad truth is that incentives have diluted the importance of investment philosophy in recent decades. While well intentioned and hard working, corporate executives and money managers too frequently prioritize growing the business over delivering superior results for shareholders. Increasingly, hired managers get paid to play, not to win.

So ask the tough question: Does an intelligent investment philosophy truly guide you or the people running your money? If the answer is yes, great. If not, figure out a thoughtful philosophy and stick with it.

dp n="30" folio="9" ? ![]()

1

Be the House

Process and Outcome in Investing

Individual decisions can be badly thought through, and yet be successful, or exceedingly well thought through, but be unsuccessful, because the recognized possibility of failure in fact occurs. But over time, more thoughtful decision-making will lead to better overall results, and more thoughtful decision-making can be encouraged by evaluating decisions on how well they were made rather than on outcome.

—Robert Rubin, Harvard Commencement Address, 2001

Any time you make a bet with the

best of it, where the odds are in your favor, you have earned something on that bet, whether you actually win or lose the bet. By the same token, when you make a bet with the

worst of it, where the odds are not in your favor, you have lost something, whether you actually win or lose the bet.

—David Sklansky, The Theory of Poker

Hit Me

Paul DePodesta, a baseball executive and one of the protagonists in Michael Lewis’s Moneyball, tells about playing blackjack in Las Vegas when a guy to his right, sitting on a seventeen, asks for a hit. Everyone at the table stops, and even the dealer asks if he is sure. The player nods yes, and the dealer, of course, produces a four. What did the dealer say? “Nice hit.” Yeah, great hit. That’s just the way you want people to bet—if you work for a casino.

dp n="31" folio="10" ?This anecdote draws attention to one of the most fundamental concepts in investing: process versus outcome. In too many cases, investors dwell solely on outcomes without appropriate consideration of process. The focus on results is to some degree understandable. Results—the bottom line—are what ultimately matter. And results are typically easier to assess and more objective than evaluating processes.1

But investors often make the critical mistake of assuming that good outcomes are the result of a good process and that bad outcomes imply a bad process. In contrast, the best long-term performers in any probabilistic field—such as investing, sports-team management, and pari-mutuel betting—all emphasize process over outcome.

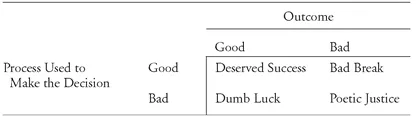

Jay Russo and Paul Schoemaker illustrate the process-versus-outcome message with a simple two-by-two matrix (see exhibit 1.1). Their point is that because of probabilities, good decisions will sometimes lead to bad outcomes, and bad decisions will sometimes lead to good outcomes—as the hit-on-seventeen story illustrates. Over the long haul, however, process dominates outcome. That’s why a casino—“the house”—makes money over time.

EXHIBIT 1.1 Process versus Outcome

Source: Russo and Schoemaker, Winning Decisions, 5. Reproduced with permission.

The goal of an investment process is unambiguous: to identify gaps between a company’s stock price and its expected value. Expected value, in turn, is the weighted-average value for a distribution of possible outcomes. You calculate it by multiplying the payoff (i.e., stock price) for a given outcome by the probability that the outcome materializes.2

dp n="32" folio="11" ?Perhaps the single greatest error in the investment business is a failure to distinguish between the knowledge of a company’s fundamentals and the expectations implied by the market price. Note the consistency between Michael Steinhardt and Steven Crist, two very successful individuals in two very different fields:

I defined variant perception as holding a well-founded view that was meaningfully different from market consensus.... Understanding market expectation was at least as important as, and often different from, the fundamental knowledge.3

The issue is not which horse in the race is the most likely winner, but which horse or horses are offering odds that exceed their actual chances of victory.... This may sound elementary, and many players may think that they are following this principle, but few actually do. Under this mindset, everything but the odds fades from view. There is no such thing as “liking” a horse to win a race, only an attractive discrepancy between his chances and his price.4

A thoughtful investment process contemplates both probability and payoffs and carefully considers where the consensus—as revealed by a price—may be wrong. Even though there are also some important features that make investing different than, say, a casino or the track, the basic idea is the same: you want the positive expected value on your side.

From Treasury to Treasure

In a series of recent commencement addresses, former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin offered the graduates four principles for decision making. These principles are especially valuable for the financial community:

5 1. The only certainty is that there is no certainty. This principle is especially true for the investment industry, which deals largely with uncertainty. In contrast, the casino business deals largely with risk. With both uncertainty and risk, outcomes are unknown. But with uncertainty, the underlying distribution of outcomes is undefined, while with risk we know what that distribution looks like. Corporate undulation is uncertain; roulette is risky.6

The behavioral issue of overconfidence comes into play here. Research suggests that people are too confident in their own abilities and predictions.7 As a result, they tend to project outcome ranges that are too narrow. Over the past eighty years alone, the United States has seen a depression, multiple wars, an energy crisis, and a major terrorist attack. None of these outcomes were widely anticipated. Investors need to train themselves to consider a sufficiently wide range of outcomes. One way to do this is to pay attention to the leading indicators of “inevitable surprises.”8

An appreciation of uncertainty is also very important for money management. Numerous crash-and-burn hedge fund stories boil down to committing too much capital to an investment that the manager overconfidently assessed. When allocating capital, portfolio managers need to consider that unexpected events do occur.9

2. Decisions are a matter of weighing probabilities. We’ll take the liberty of extending Rubin’s point to balancing the probability of an outcome (frequency) with the outcome’s payoff (magnitude). Probabilities alone are insufficient when payoffs are skewed.

Let’s start with another concept from behavioral finance: loss aversion. For good evolutionary reasons, humans are averse to loss when they make choices between risky outcomes. More specifically, a loss has about two and a half times the impact of a gain of the same size. So we like to be right and hence often seek high-probability events.10

A focus on p...